A new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) takes a close look at the changing landscape for global energy investment, painting a picture of a world in midst of an epochal energy transition. The collapse of oil prices since 2014 has led to a sharp cutback in exploration for hydrocarbons, while at the same time investments in renewable energy continue to rise. “We see a broad shift of spending toward cleaner energy, often as a result of government policies,” IEA Executive Director

Fatih Birol said in a statement. Nevertheless, with the world still highly dependent on crude oil in the transportation sector and upstream spending continuing to get slashed, many questions continue to arise about long term security of supply.

Oil and gas spending falls sharply

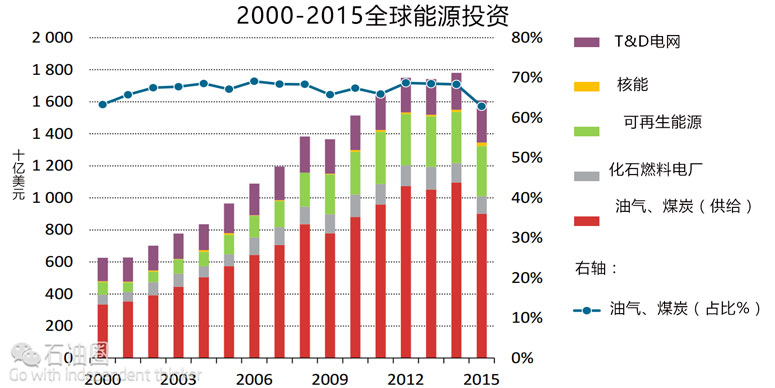

Between 2000 and 2014, upstream investment in oil and gas grew by about 12 percent per year on average, rising roughly five-fold over that 15-year period from $160 billion to $780 billion.

But the collapse of oil prices in 2014 ended the growth cycle. Global upstream oil and gas spending fell to $583 billion in 2015, down about 25 percent from the year before. The reductions will continue this year, with spending expected to fall by an additional 24 percent to just $450 billion. The 2014-2015 period is the first time in forty years that investment fell for two consecutive years, and the combined loss of about $300 billion, the IEA says, is “an unprecedented occurrence.”

The trend could continue through next year. “It may well be the case that investment will fall in 2017,” Fatih Birol said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. “We have never seen [a three-year decline] in history,” he said.

For the oil and gas industry, there is a silver lining to some of these grim figures. The IEA estimates that about two-thirds of the decline in spending is a result of cost deflation, reflecting the savings achieved from lower oil prices, cheaper equipment, and markdowns squeezed out of oilfield service companies. The IEA Upstream Capital Cost Index declined by 15 percent in 2015 and is expected to fall by another 17 percent this year. Nevertheless, the other one-third of the roughly $200 billion decline in oil and gas investment in 2015 stemmed from a drop in activity.

Shale spend down 52%

The upstream capex cuts have hit some parts of the world far more severely. “American shale and global offshore spending have been hit the most,” as the impact of low oil prices on cash flow has “tested the debt-financed investment model of the US shale oil industry,” the IEA says.

The US shale sector has seen an overall 52% fall in investment over the past two years, with the smaller independent companies at the heart of the sector seeing their upstream capex fall by an eye-watering 72% between 2014 ($124bn) and 2016 ($35bn). Given this spending collapse, the country’s oil output (including NGLs but excluding ‘renewables’) of 12.00mn b/d for August, still within 1mn b/d of the 12.94mn b/d April 2015 peak, has been incredibly resilient.

Of course, longer-term US and Canadian unconventional plays have accounted for the key rise in global upstream capex since the start of the century. Shale gas and oil sands drilling is “typically more capital-intensive than conventional fields” leading North America’s share of upstream global oil and gas spending to soar since the turn of the century, hitting a third of the global total by 2015. The region accounted for almost half the total increase in upstream spending between 2000 and 2014 according to the IEA.

Rising share of global spend in Middle East

The Middle East and Russia, however, have avoided meaningful cuts in energy investment. Home to some of the cheapest oil in the world, Russia and countries in the Middle East have plenty of oil projects that are still profitable in a world of sub-$50 oil. In fact, low oil prices create a greater impetus for upstream investment in oil-exporting countries—lower revenues must be offset with higher volumes to support their budgets.

The region gets more bang for its buck “due to exceptionally low drilling costs,” the IEA notes. The Mideast share is actually up from the 10% average figure over the past 10 years. MEES back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that the region’s relative resilience has seen its share of global upstream spending rise to 16-18% this year.

As a result, it is not surprising that national oil companies (NOCs) accounted for an all-time high of 44 percent of global oil and gas investment, meaning future demand growth will likely be met by producers that have unstable political environments.

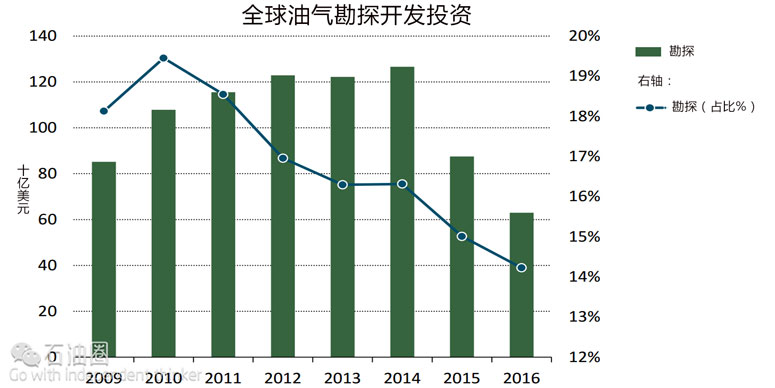

Exploration expenditures fell by 30%

Spending on exploration has been hit particularly hard. Oil and gas companies are increasingly focusing their efforts on developing proven reserves rather than spending scarce resources on risky exploration endeavors. Oil and gas exploration expenditures fell by 30 percent in 2015 to $90 billion, and will drop to just $65 billion this year. Exploration accounts for only about 14 percent of upstream spending so far in 2016, the smallest share in a decade, the IEA says.

With companies abandoning exploration plans, new oil discoveries hit a 70-year low in 2015. Only 2.7 billion barrels were discovered last year, the worst result since 1947, according to Wood Mackenzie. The industry may log only a fraction of that total this year, with discoveries at just 736 million barrels through the end of July.

Spending on the development of proven oil reserves is also falling dramatically. Last year, the oil and gas industry gave a greenlight to only a handful of major projects that accounted for about 6 billion barrels of oil. That is only about one-third of the five-year average. High-cost projects were of course scrapped first, with Canada’s oil sands and Brazil’s deepwater seeing some of the heaviest cuts.

Clean energy transition

The latest IEA figures answered many questions about the future for renewable energy. Global investment in renewables-based electricity generation hit $288 billion last year, capturing about 70 percent of total investment in power generation. Astonishingly, renewables saw more than two-and-a-half times the investment that fossil fuel generation received. Oil may still dominate the transportation sector, but renewables are now the largest source of investment in the electric power sector.

Critics of renewable energy point out that the amount invested in renewables in 2015 was actually 2 percent lower than the year before. In fact, investment in renewable power generation has been roughly flat since 2011. But that statistic is misleading—the investment in 2015 led to one-third more electricity generation capacity. That reflects the sharp fall in costs for renewable technologies.

Not fossil fuel-free yet

Renewables have made impressive progress, and investment will continue to shift toward cleaner energy. However, government policy will be a pivotal factor in the rate of growth for renewables. National policies have helped solar and wind scale up, and the Paris climate agreement last year laid out some commitments—or at least aspirations—for a more renewables-based energy future

Meanwhile, even as renewables are playing a larger and ever-expanding role in global electricity markets, oil still dominates the transportation sector, and will continue to do so for some time. Spending on exploration and production has been savagely cut because of low oil prices, which could ultimately lead to a much tighter oil market in the future. New sources of supply cannot turn on a dime. The IEA has sounded the alarms on a supply shortfall in the future. With the speed and scale of spending reductions happening at a dizzying pace and the subsequent loss of human capital also occurring, the industry will likely be flat-footed when oil prices rebound. Moreover, upstream oil and gas investment is now “increasingly concentrated in regions exposed to geopolitical and security risks.” When the market tightens, it may be difficult for oil companies to meet the challenge.

石油圈

石油圈