Oil Market Jigsaw Puzzle: Putting The Pieces Together

THE data has long told us that the efficiency of the US shale oil process is constantly improving.

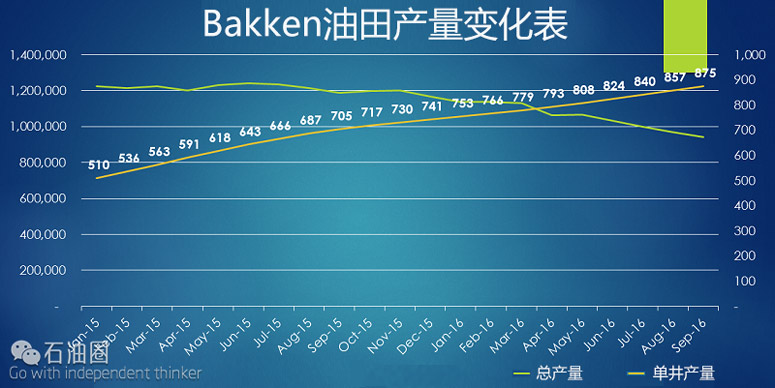

For instance, the above chart shows that in just in one shale-oil field in the US – the Bakken in North Dakota and Montana – the amount of oil each well can produce improved by 72% between January and September of this year. And from January 2007 – when the EIA data begins – until September 2016 the increase is no less than 648%.

The EIA data show similar rates of efficiency increases across other US shale-oil plays.

This data series has been telling us since as early as January 2007 about the quite breath-taking pace of innovation in the US shale-oil industry.

Talking to lots of people in the oil business has next provided an understanding of how this innovation has been achieved -and, crucially, the likely extent of further progress.

A third and equally important piece of this jigsaw puzzle has been the economic, social and political context in which both the US shale oil and gas industries is operating. In a post-Economic Supercycle world, the prospect of energy independence is one of the few genuine bright spots in the US economy.

Click these three pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together and you know this: Claims that the absolute, minimum break-even price of coal for the US shale oil industry has already been reached cannot be true.

OPEC’S Production Strategy

The next piece of the jigsaw puzzle relates to Saudi Arabia. The Saudis have, of course, vast experience in exploring for and extracting oil, and so understand the industry very well. This should have prompted this question: ‘Should I follow the consensus view that Saudi Arabia’s market-share strategy- i.e. pumping more oil despite the post-September 20145 fall in prices – is about getting rid of the US shale oil industry?’

Your answer should have be of course ‘No’, which leads to the question of why Saudi Arabia is pursuing this strategy.

I think it is instead because Saudi Arabia and other major producers don’t want to risk being forced to leave their most-value valuable national asset in the ground. The reasons is that they understand that we have gone beyond peak demand growth for oil.

They also believe that US production costs will continue to fall because of the flexibility of the shale-oil process. This would make OPEC production cuts deep enough to raise oil prices self-defeating. Such cuts would encourage more shale-oil production and investment, making any rally in oil prices short-lived.

The reality is instead that OPEC has lost some of its ability to influence the price of oil. This is again because we have gone beyond peak demand growth – and because of developments in the US shale oil business.

Vision 2030 – the Saudi blueprint for its economic future, which was released in April – is another piece in the jigsaw puzzle.

I think it shows the Kingdom’s determination to go beyond a heavy economic dependence on direct oil exports. This will be through more investments downstream of oil in, for instance, more refineries and petrochemicals plants.

Vision 20103 can be partly seen as an admission that oil exports alone cannot deliver the revenues needed to secure the country’s economic future – because we are in a much-lower oil price world.

Another key objective of Vision 2030 is to create more employment for a very youthful population. As you go ever-further downstream from barrels of oil, job creation increases.

The Main Influence on Oil Prices Since 2008

A further piece of the puzzle is to understand the biggest single influence on oil prices since the Global Financial Crisis. It seems to me to have been this:

The search by pension funds and other investors for an alternative ‘store of value’ as a result of thesome 672 interest rate cuts by the world’s top 50 central banks since 2008.

This has led to big overall increase since 2008 in the amount of crude traded on futures markets.

We all know that the bubble went pop in September 2014, when it became clear that demand for oil was nowhere near as robust as people thought. Events in China served as the wake-up call here.

Since then, despite weak underlying supply and demand fundamentals, oil prices have staged several mini recoveries.

Putting All Of This Together: Oil Prices in Q4 2016

You need to model a scenario where prices once again start to retreat towards their long-term average of$26/bbl in Q4 of this year.

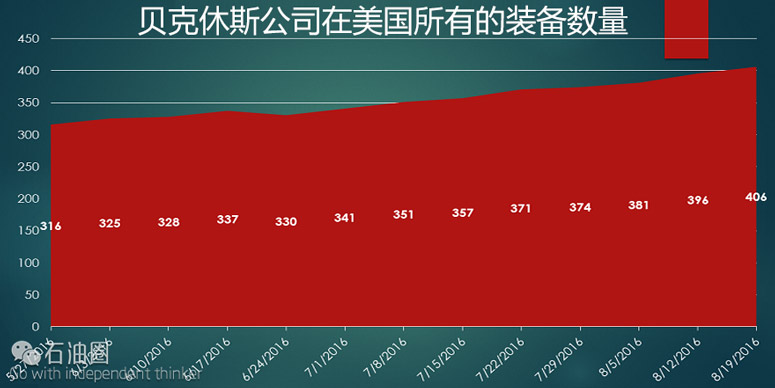

Why? First of all, combine the chart at the beginning of this post with the one below:

This second chart shows that since a 2016 low of 316 US oil rigs in operation in May, the number of working oil rigs had increased by 28% up to 19 August. The US rig count has now risen for eight weeks in a row.

A higher rig count- which is in response to the recent rally in crude prices – obviously means more US production, as does continuing improvements in efficiency of each well.

Why have prices gone up over the last few weeks? Because of the rumour that the OPEC informal meeting on 26-28 September will result in a production freeze.

But given what I have described above, you have to question whether there is any real substance behind these rumours.

And say if I am wrong, would a production freeze even work? Probably not. Only deep production cuts might do the trick – and, as I have again described above, such cuts would very likely only have a short-lived influence on oil markets.

Global oil demand growth is expected to slow from 1.4 mb/d in 2016 to 1.2 mb/d in 2017, as underlying support from low oil prices wanes. The 2017 forecast – though still above-trend – is 0.1 mb/d below our previous expectations due to a dimmer macroeconomic outlook. The 2016 outlook is unchanged from last month’s Report.

Another other concern is oil in storage. Inventories of oil and refined products increased by 6.6m bbl in the week ended August 19 to a record 1.4bn bbl, according to the EIA.

The 26-28 September informal OPEC meeting is obviously a key date for your diary.

So is the release of the October industrial production, import and export data for China. This is likely to show a further slowdown in all these key indicators as Xi Jinping’s economic reforms accelerate.

I suspect that if these same data points are negative in September, this will be partly seen by oil markets as being the result of the production shutdowns resulting from the 4-5 September G20 summit in Hangzhou. Hence, my reason for thinking that the October data will be more significant.

Clearly, the downside might not be realised in Q4 because there are no guarantees that the ‘trigger factors ‘I have listed above will occur.

Or even they do happen, further unexpected supply disruptions might keep crude firm. The Canadian wildfires and attacks on Nigerian pipelines were behind price rises earlier this year.

But it’s all about thorough scenario planning, which has become absolutely essential as a result of the end of the Economic Supercycle. This is why companies need to model the possibility that during Q4, crude will resume its retreat towards its long-term average of $26/bbl.

石油圈

石油圈