Your Royal Highness, Prime Minister, Your excellencies, Ladies and gentlemen.

It is great to be back in Norway.

There is a classic story about one of the most famous Norwegians of all time, the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Lying on his sickbed, he overheard his nurse saying that he was a bit better that day.

Ibsen sat up in bed and said in a clear voice: “Tvert imod” ― on the contrary. And this was the last thing he ever said.

Ibsen was indeed a contrarian, a character type no society should do without. Questioning commonly held beliefs with good reason is vital for tackling societal challenges.

And when it comes to some of the beliefs about the challenge of the energy transition, which may be founded on less than solid fact, our industry should not shy away from being the contrarian in the room.

All of us here today have a pivotal role to play in shaping the energy system of the future. With our knowledge, we have some indispensable ― and you could say, contrarian ― insights to offer.

Please allow me to explain.

As we all know, the demand for energy is expected to grow. By 2035, according to the new policies scenario of the International Energy Agency, demand could be a quarter higher than last year.

Just as demand will go up, emissions of greenhouse gasses will need to come down… especially if the world is to live up to the significant and ambitious Paris agreement on climate change.

The underlying question is: How far can countries transform their economies to meet demand and reduce emissions at the same time? And, crucially: How fast can they do that?

Social, political and geographical conditions differ from country to country. So the energy transition is likely to play out in a different way in different places. Norway can use hydropower for example, while other countries don’t have that option. The pace of the transition will differ too. In some places it will be relatively fast, in others relatively slow.

Renewables have a major role to play in the energy transition. But sun, wind and water chiefly produce electricity. And, at least for the moment, there are some serious limitations to widespread electrification.

Roughly speaking, you can divide the energy system into four sectors: power, transport, industry and buildings. All four of them face their very own, very different challenges on the road to electrification.

Without hydrocarbons, for example, long distance air travel and heavy road transport are not yet feasible on a large scale.

To make essentials like iron, steel and cement, you still need hydrocarbons that can produce high temperatures.

Making buildings all-electric can be very challenging, especially in places where people would basically have to leapfrog from woodstove to electric cooker.

And densely populated regions may well find it difficult to power their megacities on renewables alone. This is because the sun does not always shine and the wind does not always blow. And because there is a limited amount of space available for solar and wind farms.

So even if we stretch the limits of today’s technologies, the world cannot yet live on renewables alone. Indeed, it will already be a major challenge for the share of renewables in the energy mix to grow sufficiently.

The first generation of wind and solar technologies left the lab in the 1970s and 80s. Decades later, these renewables account for around 1% of the global energy mix. Moreover, electricity is only 18% of final energy consumption.

To fight climate change, the share of electricity will need to increase rapidly ― and all at a time when the energy system as a whole is growing.

In other words, this century’s energy landscape will inevitably be a patchwork of renewables and hydrocarbons. Or, to put it differently, some level of emissions will remain for some time.

I believe it is part of our industry’s role to underline this undeniable truth. It is part of our role to be the contrarian in the room. Not because we like it, but because realism is absolutely crucial to achieving an effective and efficient energy transition.

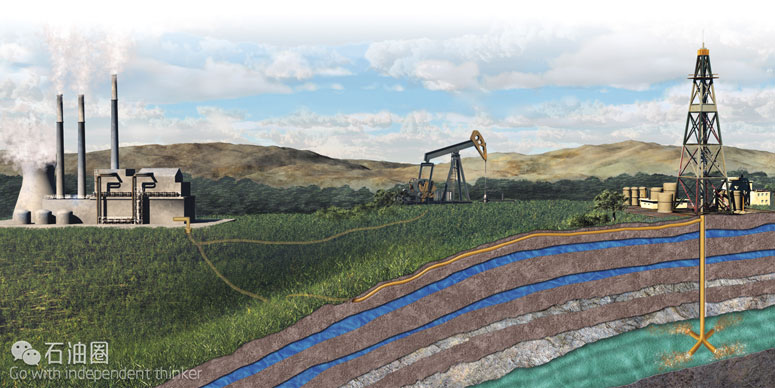

Building on this realism, we need to offer practical solutions that will help shape the energy transition. Carbon capture and storage is one of these solutions. CCS can capture CO2 from power plants and industrial sites and store it safely under the ground.

Shell operates a pioneering CCS project called Quest in Canada and we’re involved in a number of other CCS projects around the globe ― including a test facility in Mongstad, Norway.

Our industry needs to reduce its carbon intensity too. This is one of the reasons behind Shell’s strategic choice for natural gas. When burnt to produce electricity, gas emits half the CO2 and just one-tenth the air pollutants of coal.

Reducing our carbon intensity is also one of the reasons why a new generation of energy sources has a more prominent role in Shell’s new strategy. As we have explained to our investors, new energies like wind, hydrogen and biofuels will become essential parts of our portfolio over time.

Before I finish, ladies and gentlemen, let me acknowledge that it is far from easy to be the contrarian in the room. And I can tell you from my own experience it is not always comfortable either. But I believe it is the very essence of leadership in the energy transition.

I trust you will join in working with governments, companies and civil society to help shape a viable energy future. Together we must show the world that our industry is an invaluable part of that future.

Thank you very much.

石油圈

石油圈