With OPEC out, is this what the new normal looks like for the oil and gas industry?

Last Wednesday’s 1.1 million-barrel build in U.S. crude oil inventories drove West Texas Intermediate crude prices down by roughly a buck. A couple of days before, rumors of OPEC having a special meeting to look at possible price support sent markets up a buck and a half.

New reports every few days from the EIA, OPEC, IEA, business media and others trigger kneejerk market reaction from oil buyers and sellers. Is this the signal that what we are seeing in 2016 is the new normal for oil prices?

It was like a bulldozer ripping into a grassy hillside: the oil and gas industry was abruptly re-landscaped in 2014. It happened suddenly and decisively on Thanksgiving Day.

That was when Saudi Arabia/OPEC conceded its role as swing producer for global oil markets by choosing not to cut production. They said they wanted to protect their global market share. For almost two years since, the industry has been stinging because of Saudi Arabia/OPEC’s sudden and unexpected departure from its role of guiding the oil markets.

In the 21 months since Thanksgiving Day of 2014, price volatility has become the norm, not the exception. From a comfy world of $100+ oil in 2014, to the glut-induced bottom of $26 per barrel in early 2016, oil markets have been unpredictable. The wild ride has left some running for the exits. Others have settled in, sharpened their pencils and hunkered down.

A New World for Oil: Does Supply Dictate Price or Does Price Dictate Supply?

The new oil industry landscape has delivered more questions than answers:

Are oil prices entering a range-bound dynamic or are will they continue to be susceptible to crazy swings? Are volatile price swings the new normal? When will oil markets find equilibrium and provide the basis for a new trend, with greater resistance to volatility?

In the past, the price of oil was largely dictated by OPEC. The cartel producers throttled back or ramped up production in accord with the balance of supply and demand, with the intent of keeping the oil price stable and supply steady. That was part of the OPEC mission. The essence was that the supply of the world’s oil was going to be under the control of one group (OPEC), and those members would agree to closely govern supply in a way that would result in a desired price.

But then on Thursday, Nov. 27, 2014, OPEC relinquished its role as swing producer and that dynamic gave way to a new mandate: no longer is the world’s supply of oil controlled by a cartel, and no longer will the price be dictated by OPEC’s ability to keep a tight grip on that supply.

Meet the new swing producers. They are more than 7,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean from the old swing producers, occupying the offices of independent North American oil and gas companies. Global production and supply, once controlled by a Saudi oil worker who was told to turn a choke valve in the Ghawar Field, now lives in the oilfield economics spreadsheets sitting on the desktops of the shale boom’s leadership–energy executives in Houston, Denver, Midland, Oklahoma City, Dallas, Tulsa, and Calgary. These are the people who now control the global oil supply.

In today’s OPEC-hands-off environment, oil prices are going to be dictated by how the American oil and gas c-suites interpret the detailed economics of getting oil out of the ground. Business decisions about how, where and when to drill will never again be guided by the belief that “OPEC will never let the price fall below $70 per barrel.”

CEOs, COOs and CFOs with sharp pencils and an exceptionally tight grasp on well economics are the new faces of the people who control the global oil supply.

OPEC’s hands-off approach shows it is not interested in controlling supply in order to dictate price. Instead, a few hundred swing producers in North America will now dictate supply. And what dictates their actions? The price of a barrel of oil.

The Capitalist Dynamic

With any new market dynamic, there is a period of adjustment. When a new product is launched in a free market, capitalist economy, the product is unveiled and an initial price is established and, with no competition, the product is priced higher than it will eventually settle. Then, other producers enter the game and create a competitive environment, which drives the price down. Eventually, producers settle in to find their optimum levels of production, and the price of the item stabilizes. Volatility gives way to an equilibrium between supply and demand.

Certainly a barrel of oil is not viewed in the same way as the latest smart phone, plasma TV or a ShamWow, but the idea of market forces establishing the new median is relevant to crude oil, and in the last few months, we have started to see signs that a new equilibrium could emerge, particularly in the U.S.

Many in the West speculated that OPEC’s real strategic intent by ceding the swing producer role was to open a can of you-know-what on American shale drillers. Force them to slash capital investment—payback for the United States becoming the world’s dominant oil producer in 2014, courtesy of the shale revolution.

There have been dreaded layoffs, asset sales and bankruptcies in the North American oil and gas industry, but the American oil market has proven to be resilient.

This is evidenced by domestic production increasing for many producers at the same time as the number of wells they are drilling has declined. Companies have cut costs, scaled back capital investment, and found new efficiencies in their daily operations.

Independent shale developers routinely report when they shave days off of their drilling and completion times. Every quarter since the OPEC decision, North American shale drillers have gotten better at cutting costs associated with getting their oil and gas out of the ground. The best run companies are no longer just “surviving a downturn,” they are finding ways to be successful in the new price environment.

There is an overwhelming accumulation, quarter after quarter, of new efficiencies–from pad drilling, new completions, fewer drilling days, new technologies. These constant improvements are resulting in far lower well cost figures being reported by almost every shale producer every quarter.

Proof of success: the executives running North America’s independent oil and gas companies have figured out how to work within the new rules dictated by the new normal.

Crux of the Matter: U.S. Oil Supply Levels are Moving the Meter

The chart below shows U.S. field production of crude oil on a weekly basis since November 28, 2014. For the week ended Nov 28, 2014, production was 9,083 MBoe/d. This was the lowest level of weekly production on record until February 26, 2016, when production came in at 9,077 MBoe/d.

Outside of the oil industry, it might seem odd that as price continued to fall, U.S. producers held production largely flat and in some cases production was increasing. There are a myriad of reasons as to the rationale behind the continuation of drilling activity: stave off bankruptcy, contracts in place, maintain lease agreements, lock in cash flow, and so on. The level of production during this period was indicative of many factors, not just the state of the oil market.

The most recent peak of production came during the week ending January 15, 2016, with a production level of 9,235 MBoe/d. This was the highest level since August 2015. A key observation is that the last weekly production high occurred on January 15, 2016, and without looking at the chart, take a guess as to what the oil price was on that day? The WTI oil price closed at $26.21, the lowest closing price of the current downturn. Following the week of January 15, oil production levels have consistently declined with only two small gains in weekly production through the beginning of July 2016.

What was the first week of significant gains in U.S. production levels following the downturn that ensued from January? The first week of relevant gains came on the week of June 3, 2016, when oil production went up 10 MBoe/d for the week. What was the oil price at that point? The recent high came on June 8, 2016, at a closing price of $51.23 per barrel.

Another indicator is rig count. Production from legacy assets need to be replaced as wells are depleted and shut down. New wells are drilled and production from them is brought on line. What was the first weekly gain in operational rig count since August 2015? You guessed it, the week of June 3, 2016. The same week as the recent high in oil price.

Well completion times have been among the operational efficiencies that U.S. drillers have gained in the past year and a half. Time from well spud to production has decreased across the board. As a generality, the industry has reduced drilling and completion time from a month or more, down to a few weeks, and in some instances, just days. This has allowed operators to replace production at a faster pace than before, allowing for a more immediate effect on overall U.S. production.

The point being made is this. From Nov. 2014 until early 2016, oil and gas companies in the U.S. largely ignored the market forces that were pulling. They were focused on survival and continued to drill, produce and sell their oil to keep cash coming in the door. But as prices drop and cashflow shrinks, debt load on balance sheets becomes suffocating. With a wave of E&P and oil service company bankruptcies already in the books, companies have high-graded their assets, some have acquired or divested assets, and operators across North America have slashed costs to stay in business in the depleted price environment—the new normal.

Oil Supply: Whose Foot is on the Accelerator?

If oil supply in the U.S. is influencing the global supply and demand balance, it is worth a look at what is driving U.S. production.

Decision making for oil and gas companies in the U.S. comes down to economics, location, and the return that is generated by each barrel of oil that is produced. Well costs and IRRs have become the dictating factors instead of drilling because that’s what we do to generate enough cash flow to pay interest expenses.

With two economic systems – capitalism (U.S.) and central planning (Saudi Arabia and OPEC) – coexisting in the oil markets, the incentives for the OPEC central planners has changed. They too are now operating in a new world. It’s a world in which America is the world’s largest oil producer in an oversupplied market.

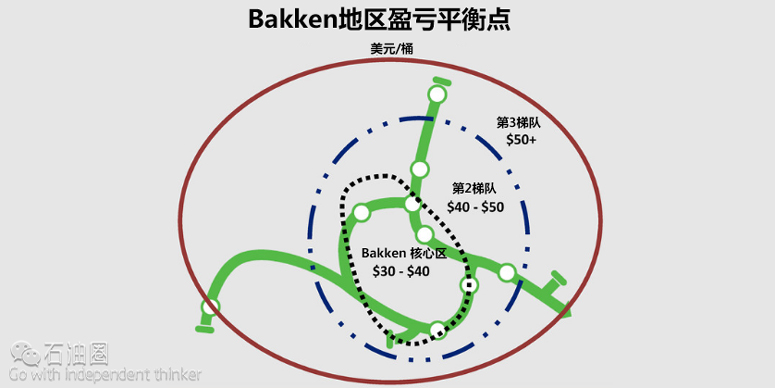

In the American free market economy, oil companies drilling and producing in the “core of the core” can realize an economic return on investment at lower oil prices than those on the periphery of the core. The “core of the core” would entail a Tier 1 position. The Tier 1 acreage holders will continue to drill and produce their Tier 1 acreage because it’s where they can produce the most volume of oil for the lowest drilling costs.

Saudi Arabia abdicated its swing producer role to a group of “accidental” swing producers – the North American shale players who hold Tier 2, Tier 3 and Tier 4 acreage outside the “core of the core” of the most prolific plays.

The decision making process to drill and produce Tier 2, 3, and 4 acreage becomes a little more complex, because costs are higher and EURs are often lower than in the Tier 1 acreage. The one factor that drives the decision is what will the return be on the investment? And that decision is dictated by the price that a producer will receive when they sell the product to generate revenue. Oil price is dictating drilling decisions which in turn dictates the available supply.

The central planning economic model uses supply to control the price, the capitalist/free market approach uses oil price to dictate supply. Since these producers cannot by law act in collusion, the way a cartel would, it is not so much that they are swing producers, but rather, North America’s market-based economy has become the “swing system” for the oil industry.

The concept of a swing system does not mean that central planning ceases to exist, but the role of swing producer has been bestowed on North American oil and gas companies. And in doing so it has put the economic decision making by a few hundred executives at the forefront in terms of dictating supply.

With $95 and $100 oil prices holding steady for more than three years, oil companies’ business strategy was focused entirely on growth, banks threw open the vault doors and the U.S. companies drilled everything they had. The end result was to escalate production to the point where the U.S. became the world’s number one oil producer, leaping ahead of Saudi Arabia and Russia. Then Thanksgiving Day happened and the blazing speed of the commodity downturn taught a highly leveraged industry a memorable lesson.

The shift from one market dynamic to the next didn’t happen overnight. There was a learning curve for the shale producers.

The North American oil producers’ swing system will reach a place where price stability is attainable, and that will become the new norm. It won’t be the same environment in which OPEC says, “Yeah, $95 a barrel sounds good, let’s keep it there.” However, in the new normal, the decision making is based upon companies’ IRRs, price decks, hedging and cash flows. Good accounting will determine supply.

What Does the Future Hold for Oil?

Hypothetically, if oil were to move to $70 tomorrow, rigs would pop up all over the U.S. landscape, increasing total production, adding barrels to supply, pushing the price back down. Consequently, if oil falls to $20, rigs will be laid down, production will fall and price will increase. The key will be to find a balance where the swings in rig count and production are mitigated, and the oil price finds a level where there is stability. Then oil producers in the U.S. and Canada will move forward in accordance with oil market dynamics. When that happens, the global landscape of oil will shift towards a balance, and price swings will be met with measured activity, instead of cathartic release.

In the past, the world’s supply, which dictated the price of oil, was in the hands of OPEC. In the new environment, the price of oil will dictate the drilling and development decisions made by the Tier 2, 3 and 4 acreage holders. And their actions will determine the ultimate level of supply.

石油圈

石油圈