Geopolitics are always a wildcard for the energy industry. Canada’s politics demonstrate that truth. The election of Rachel Notley, leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP), as Premier of Alberta in May 2015, kicked off a period of increased anxiety and uncertainty about the future of the province’s energy and environmental policies. That political change was followed five months later by the surprising election of the Liberal Party to rule the nation. The election results were a surprise because the Liberal Party and its leader Justin Trudeau had been given little chance of achieving an outright majority in Canada’s Parliament.

In matter of six months, the energy business went from operating under conservative and supportive governments in Alberta and Ottawa to trying to determine how tax and environmental policies would be changed under liberal politicians. It was immediately obvious to energy industry participants following Ms. Notley’s election that the cost of operating an energy business in Alberta would increase given her party’s push to extract greater revenues from those companies. At the same time, the push for greater environmental regulation in Alberta chilled confidence about the pace of energy business growth.

The federal election reflected a rejection of a fourth term for Conservative Party leader Stephen Harper and his pro-energy policies. That position was demonstrated by the Prime Minister’s aggressive support for the Keystone XL pipeline that was ultimately rejected by U.S. President Barack Obama. The surprise election of Mr. Trudeau as Prime Minister caused many residents to scramble to discern whether his campaign rhetoric, especially about new energy projects and environmental policies, would become reality, or was merely designed to gain votes.

Mr. Trudeau, the son of Pierre Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada from 1968 to 1984, was dismissed by many during the campaign for his lack of political experience. They said he was trading on the name and fame of his father. By leading his party into a majority position in the Parliament, Mr. Trudeau’s stature was raised. It was further elevated when President Obama embraced him as a kindred soul on social and environmental issues. The two leaders combined to push through the Paris Climate Change agreement, which improved Canada’s stature in the environmental world. The real measure of Prime Minister Trudeau’s elevated stature was being hosted by President Obama at a state dinner, something Mr. Harper was never offered during Mr. Obama’s first seven years in office.

The increase in taxes, a new royalty regime in Alberta and new rules for evaluating the worth of new oil and gas pipelines in Canada has the energy business on edge. The global oil and gas industry downturn has devastated the Canadian industry causing significant capital spending cuts, substantial layoffs of both field and home office staffs, and dramatic financial restructuring. The impact of the downturn on the industry is now being assessed as executives are finally gaining a perspective on the magnitude of the damage. Executives are also recognizing the difficult position of the Canadian energy industry as they search for catalysts to help revive the business. For energy, the issue is simple – Canada is rich in oil and gas resources, but it lacks sufficient access to world markets. The Canadian crude oil resources are among the largest in the world, if one counts the country’s oil sands reserves. However, the Canadian oil and gas industry was built with a North American focus and with North American outlets. With the shale revolution in the U.S. boosting its supply plus an aggressive push for renewables trimming demand at the margin, Canada’s output is struggling to find market opportunities both in the United States and elsewhere. Unfortunately, the opportunities seem limited.

Like many oil-rich countries, Canada’s oil output has grown sharply since 2010 as world oil prices soared above $100 a barrel. The high price and supposed need for greater oil supply incentivized conventional oil producers to step up drilling and fracking activity along with oil sands producers expanding their existing mines and opening new ones while also stepping up in situ recovery projects. The growth in oil output convinced the pipeline industry to expand existing lines and propose new ones to the United States such as Keystone. Because expectations were that all the additional output flowing through these new pipelines would be oil sands bitumen, considered to be one of the dirtiest oils on the planet, the proposed pipelines became high-profile targets for environmentalists. As production outstripped the ability of the pipeline industry to move the supply to the U.S. market, shippers turned to railcars to get the oil there.

Canadian crude oil shipments to the United States rose dramatically during 2012, setting the stage for even more volume being shipped in subsequent years. Rail shipments fell sharply in 2015 along with the decline in oil prices. Prospects suggest that shipments of oil by rail will remain restrained as a result of the forced shut-ins of Canadian oil sands output due to the forest fires near Fort McMurray. Many oil sands producers maintain crude oil storage facilities in southern Alberta, which have enabled them to sustain their shipment volumes for a while, but the output fall will eventually impact the volumes shipped both by pipelines and rail. As the mines come back online, production and exports will rise, however, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that Canadian oil sands output will fall by an average of 400,000 barrels per day in June due to the fires, signaling that the recovery will take a while.

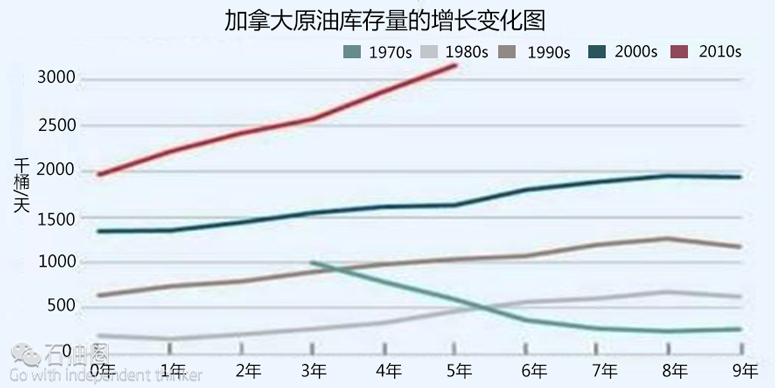

The history of crude oil shipments to the United States has shown steady growth since the 1980s. During the 1970s, Canada was a significant supplier of oil to the U.S., but that outlet was shut down as the dramatic price rise due initially to the Arab oil embargo of 1973-1974 and the Iranian revolution in 1978-1979 cut U.S. consumption. Once the world recovered from that oil industry downturn, Canada became an important oil supplier to the U.S. The recent shale revolution sent domestic output sharply higher. At the same time, high oil prices crimped consumption due to increased energy efficiency putting further downward pressure on oil use. The growth of U.S. oil supply plus new export pipelines into eastern Canada has resulted in sharply higher oil volumes moving north of the border. The net result of these trends is that U.S. oil exports to Canada now represent nearly 15% of oil import volumes coming here.

The critical issue for Canadian oil producers, especially its oil sands producers, is gaining increased access to world markets. The producers desire that outlet because without it they are subject to potentially lower prices if oil prices stay low and American refiners are unwilling to pay market prices for Canadian volumes they know the producers have to sell.

The challenge for Canadian producers due to the revival of the U.S. oil industry and the lack of alternative markets for Canadian output was highlighted in the report produced by the panel that recently reviewed Alberta’s royalty rates. The panel said, “The U.S. is now a rejuvenated force in oil and gas production, one that poses huge risks to Alberta’s market share. This is problematic, since we have long relied on the U.S. as our primary (and to some extent, only) customer, and we do not have sufficient means to move and sell our oil and gas to other countries.”

On the drawing boards are several oil pipelines that could move western Canada’s crude oil to the East and West Coasts where it could be shipped to world markets. The opposition to these pipelines is coming from the First Nations whose property is being crossed, along with the environmental movement. In the case of TransCanada Corp.’s (TRC-NYSE) Energy East pipeline to move Alberta oil across Canada to an oil export port on the East Coast, the opposition is coming from politicians and environmentalists throughout the eastern provinces.

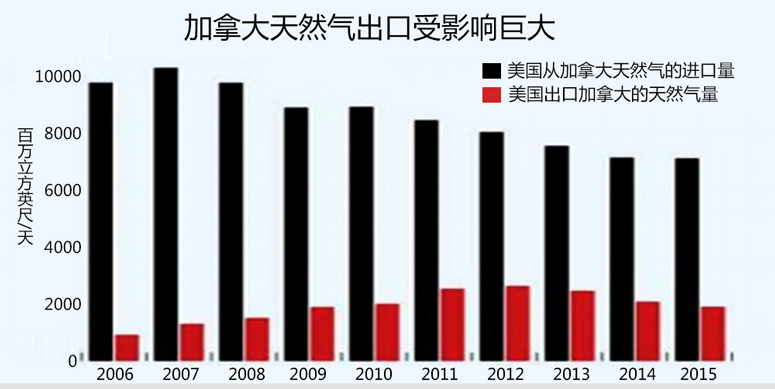

The natural gas market is also challenged by changes in the U.S. gas market and the failure of Canada to develop liquefied natural gas (LNG) export opportunities. Canadian natural gas exports to the United States peaked in 2007 and have declined steadily since. The decline coincides with the growth of U.S. natural gas output due to the success of its shale revolution. The growth in U.S. supply has more than satisfied the increased demand from more natural gas being burned to generate electricity.

In the 1990s, Canada’s natural gas exports to the U.S. grew rapidly as U.S. output fell and prospects for its recovery were considered dim. During that time, gas consumption was curtailed and natural gas prices fell to $1.00 per thousand cubic feet (mcf). The low price curtailed gas-oriented drilling, especially in the Gulf of Mexico, which was declared to be the “Dead Sea” by John Laborde, CEO of Tidewater, Inc.

Canada is also importing more natural gas from the United States, especially in the eastern provinces. These trends of falling gas imports from Canada and increased exports to Canada are shown in Exhibit 14. The dynamics of the North American natural gas market has translated into lower marketable gas output for Canada. Its gas output reached a high during the first few years of the 2000s. Production fell in 2008-2009 due to the financial crisis and recession that cut demand. Afterwards, production growth was limited by the dramatic growth of U.S. shale gas output. Between 2009 and 2015, U.S. gas output from shale grew to 37 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), nearly four times Alberta’s total production of natural gas of 10 bcf/d.

The biggest difference now between the Canadian and the U.S. natural gas markets is the pace of development of LNG export facilities. In the U.S., when it became obvious that the shale gas revolution was providing substantial volumes of supply and engineers were predicting “hundreds of years of supply growth at low prices,” domestic gas producers realized that the supply glut would depress prices. They lobbied for the right to export surplus natural gas to international markets where gas prices were higher than could be earned in the U.S. even after considering the cost of liquefying the gas, shipping it to foreign markets and re-gasifying the volumes.

Both U.S. and Canadian producers sought LNG export licenses and planned to build export terminals. Many of the U.S. proposals involved utilizing existing LNG import terminal infrastructure that only needed liquefying facilities along with the necessary export permits. Canada was not as fortunate because it lacked LNG import terminals and pipeline infrastructure. The U.S. natural gas industry was fortunate that its gas supplies were close to the coast where the LNG terminals were located, plus the interstate pipeline network to move that gas was in place.

According to the web site of Canada’s National Energy Board, there are 44 applications for LNG export permits. Industry attention is focused on the status of the proposal by Pacific North West LNG, a subsidiary of Malaysia’s Petronas for a terminal in Prince Rupert, B.C. The federal review of this proposal was due in April, but the new Canadian Environment Minister Catherine McKenna added further environmental hurdles to the review process. The most likely project to follow the Petronas one is Shell Oil’s LNG terminal at Kitimat, B.C.

The Petronas project is “on the clock” with a decision by Minister McKenna due in the next several months. If the decision is positive and there are no new restrictions on the project, then a final investment decision (FID) can be made. Assuming the project moves forward, the first Canadian LNG shipment would likely occur after 2020. The prospect that project moving forward, with possibly a second one on the horizon, would be a boost to Canadian oilfield activity. The recent industry downturn has so devastated the Canadian producing and service industries that drilling rig activity has fallen to levels not seen in decades. Without a catalyst such as the Petronas LNG project that would prompt producers to begin drilling the natural gas resources necessary to support the exports, the Canadian service industry will struggle to re-size itself and become profitable at lower levels of activity for the foreseeable future.

The future of the Canadian energy business is reaching a critical point in its history. Regulatory and market access for Canada’s oil and gas output will set the direction and pace of development for the country’s industry, and especially its service industry. The oil price recovery is a welcome salve for the damage to the industry, but the regulatory rulings on the West Coast LNG projects and Energy East will be crucial for the long-term future. Stay tuned for decisions this summer.

石油圈

石油圈