Europe increasingly dependent on oil imports, above all from Russia

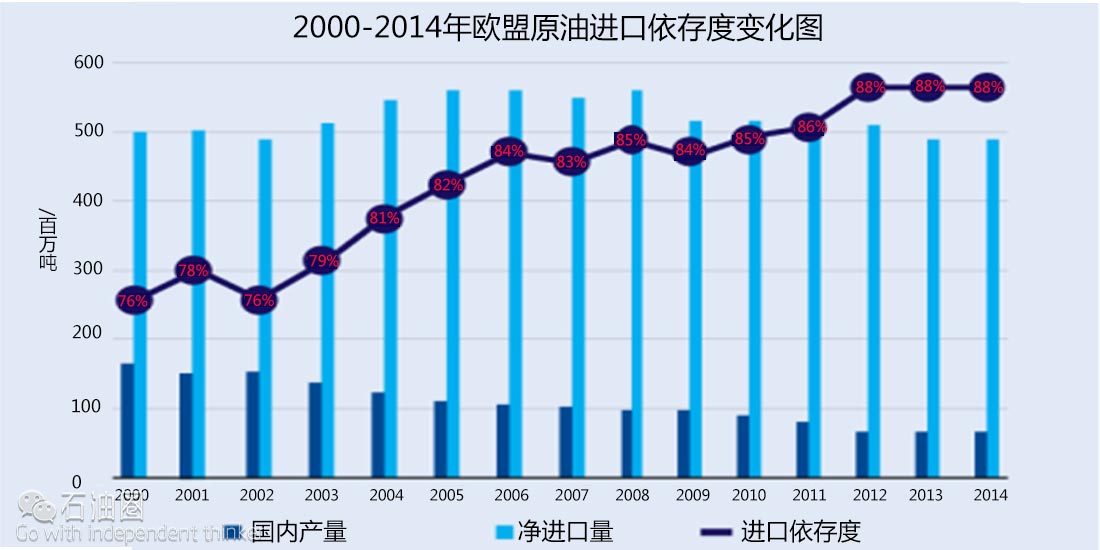

European dependence on oil imports has grown from 76% in 2000 to over 88% in 2014. The EU spends some €215 bn on oil imports, over 5 times as much as gas imports (€40 bn). Russia is the biggest supplier: dependence on Russia has grown from 22% in 2001 to 30% in 2015. These are some of the main conclusions of a study from Cambridge Econometrics made for the Brussels-based NGO Transport & Environment (T&E).

According to “A Study on oil dependency in the EU”, published on 11 July, since 2000, there has been a gradual decline in total final consumption of oil and petroleum products in the EU (on average a 1.1% reduction per annum). As a Briefing based on the study notes, this decline is due to “a reduction of oil demand outside the transport sector, improvements in vehicle efficiency, the blending of biofuels and, in more recent years, reduced demand following the recent global economic downturn.”

Despite this decline, the EU has become increasingly dependent on crude oil imports, which now amount to 88% of the region’s total consumption. Diesel imports doubled between 2001 and 2014 to €35 bn in 2014. In 2015 (when the oil price was exceptionally low), total spending on crude oil imports in the EU was €187 bn, making a total of around €215 bn, €425 per capita. According to T&E, the EU should not just be talking about gas imports when it comes to energy security, but also about its dependence on oil and diesel imports.

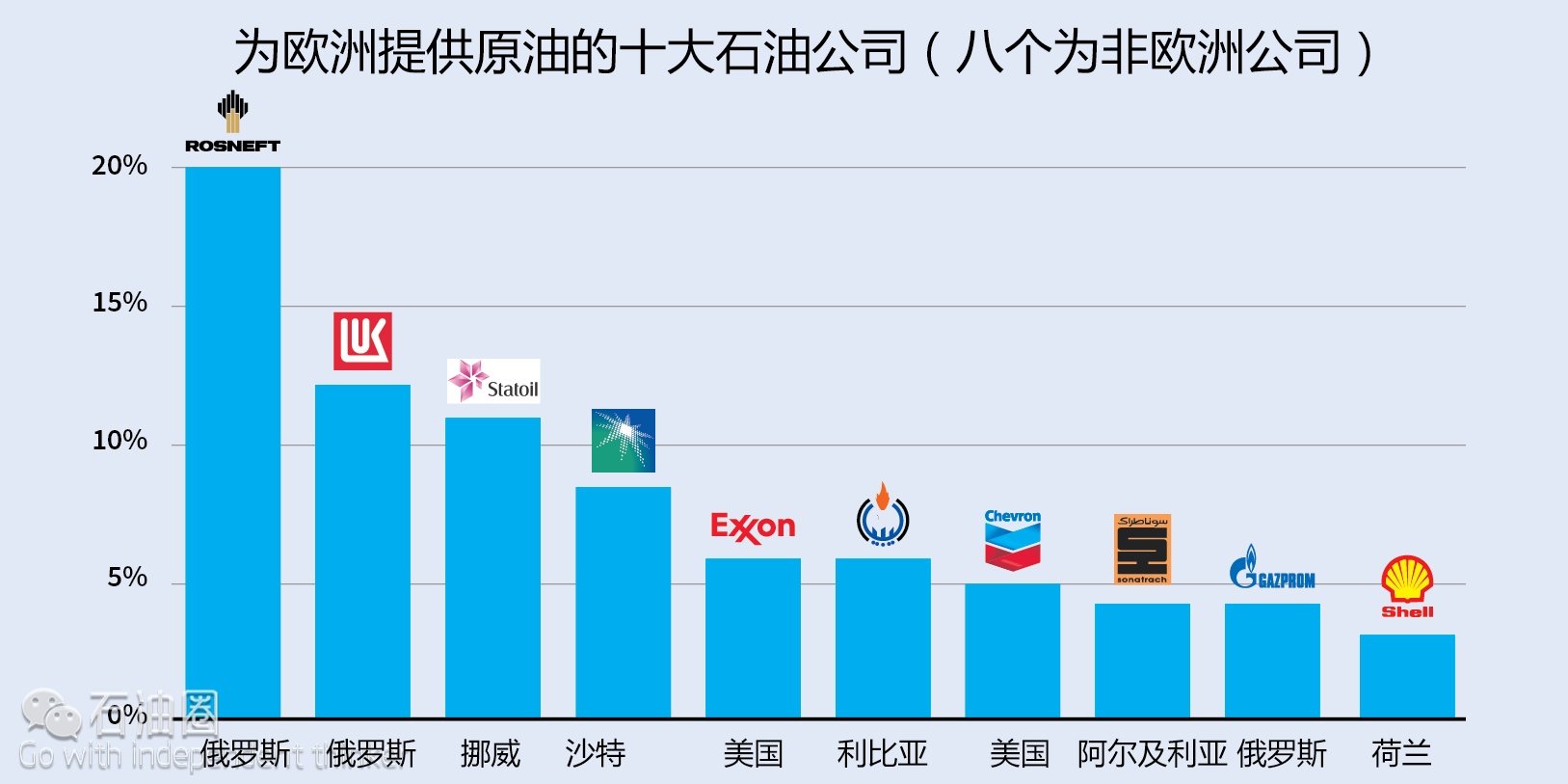

As in the gas sector, Russia is by far the largest suppier in oil. Russia accounted for one third of EU imports (around €50 bn). The report also assesses what companies instead of countries benefit from the EU’s oil imports. Over 80% of the imported crude oil in 2014 was supplied by non-European companies. Rosneft – the state-owned oil company with close ties to President Putin – is the biggest supplier of oil to Europe.

The T&E Briefing notes that “Whilst the current discussions of EU energy security as part of the Energy Union package focus mainly on gas, there is also a security of supply risk for some [Eastern European] countries when it comes to oil imports.”

The current risk of security of supply for crude oil is the highest in the ‘Visegrad’ countries (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic) and Greece: “These countries are highly exposed to the risk of supply disruption for their oil imports because of high dependence on oil supplied by pipeline from one single supplier (Russia). Greece is also exposed to a relatively high security of supply risk, due to heavy reliance on oil imports from geopolitically unstable regions (in 2014, Greece imported almost 40% of its oil from Iraq).”

Western European countries such as France or the Netherlands “are not exposed to a high risk because their oil suppliers are more diverse, and they have large import terminals that enable them to switch more easily to alternative sources of supply. To address concerns around security of supply, the EU has adopted the Oil Stocks Directive that requires EU Member States to hold oil stocks to address potential supply shortages. However, the EU will need to reduce its overall use of oil if it wants to reduce the economy’s exposure to oil supply risks, especially in high risk countries.”

T&E notes that “The transport sector is the biggest driver of oil demand at EU level – two-thirds of final demand for oil comes from transport” and “Transport is also the biggest emitter of CO2 and greenhouse gases in Europe.” So, “Reducing the EU’s energy dependency and decarbonising transport are two sides of the same coin. The EU needs to reduce its demand for crude oil and petroleum products in the transport sector if it wants to reduce its energy bill and its reliance on geopolitically and environmentally risky oil imports.”

According to T&E, the European Commission “is preparing a strategy for decarbonising transport, expected later this summer.” It recommends that this study includes:

New CO2 standards for new cars, vans and trucks for 2025:

·an integrated strategy to accelerate the electrification of transport that embraces mobility needs

·a strategy to increase the potential of emobility balancing smart, renewable grids

·an industrial policy that supports the shift to electric vehicles

·committing to go beyond global action in tackling CO2 emissions and oil use of aviation and shipping

?

T&E notes that “improved transport efficiency would also deliver substantial economic and environmental benefits. For instance, the take-up of electric vehicles and 2025 standards for cars is estimated to lead to a 1% increase in EU GDP, up to 2 million additional jobs and a 93% reduction in GHG emissions from cars and vans, by 2050.”

石油圈

石油圈