Two years ago, Reg MacDonald’s 20-day drilling classes were packed to capacity, with nearly 40 students eager to land lucrative jobs in the booming oil and gas industry. Now he is lucky if he gets half a dozen to enroll.

HOUSTON/RUNGE, Texas, July 14 (Reuters) – Two years ago, Reg MacDonald’s 20-day drilling classes were packed to capacity, with nearly 40 students eager to land lucrative jobs in the booming oil and gas industry. Now he is lucky if he gets half a dozen to enroll.

The latest rout in oil prices has been the last straw for many workers just getting back on their feet after the last downturn in 2008, said MacDonald, president of Maritime Drilling Schools Ltd in Nova Scotia, Canada, which trains both entry-level and experienced workers for oilfield jobs all over the world.

“It’s not stable. It’s too cyclical. You get ahead and you lose,” said MacDonald, who has been in the industry since the mid-1970s.

Supply outages brought oil prices close to $50 a barrel that many U.S. shale producers say they need to lift output, and drilling has picked up in some of the best oil patches.

Conversations with larger producers, contractors and suppliers suggest, however, that any recovery will look very different from the 2009-2014 shale boom that nearly doubled U.S. crude output and turned it into one of leading global producers.

The loss of thousands of workers during the two-year downturn and dearth of candidates to replace them is just one challenge. Oil professionals also talk about equipment idled for so long that it has become unusable, rising service costs, and the threat of extra supply from the backlog of drilled-but-uncompleted wells.

A Dallas Federal Reserve survey of about 200 oil companies found last month that 70 percent were optimistic that oil would fetch higher prices in a year. But it is a cautious optimism, tempered in part by oil’s 13 percent retreat in the past few weeks to around $45 a barrel.

“Oil tickled $51 dollars for about four hours,” said Raymond Welder, president of privately held Welder Exploration and Production Inc, which has more than 150 wells in south Texas. “And I must admit, I felt better on that Thursday afternoon. But it didn’t last very long.”

Engineers and Rigs

Over the next two to three years, if oil recovers, labor shortages are going hit the industry hardest, producers and recruiters say.

More than 100,000 U.S. oil and gas extraction and support jobs have been lost since late 2014, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Early retirements, minimal hiring of new graduates, and a loss of early-career professionals to other industries have reduced the workforce that will be available when the recovery takes hold.

Torgrim Reitan, executive vice president at Statoil USA in Houston, said a shortage of skilled contractors would force producers to dial down their plans if they all tried to boost output over the next six months or so.

“So many people have been let go, and so many people have left the industry,” he said. “We need to be prepared for growth in activity that needs to be at a slower pace than we thought earlier.” With energy sector jobs still scarce, some petroleum engineering graduates opt for jobs that offer more security even if they cannot match the industry’s six-digit salaries.

“I would say to future graduates – ‘do not go into this path’,” said Nick Menon, 23, a petroleum engineering graduate, who took up a job as a mechanical engineer.

To be sure, several former oil and gas employees interviewed by Reuters have said they would return if given a chance, because the money was so good.

Raising production also becomes harder with each month drilling rigs and other machinery sit idle because they often get “cannibalized” for spare parts for what is still in use.

“The capacity that we had two years ago is already crippled, and it’ll take a while to catch up,” said Jennifer Miskimins, associate professor at Colorado School of Mines in Golden, Colorado.

Bad Habit

Some of the impressive cost savings that allowed producers to survive with oil prices at less than half their 2014 peaks may also not last. While new drilling techniques helped slash costs, so did a collapse in prices of services and supplies. Now, encouraged by early stirrings of activity, some oil field services companies are raising their prices, according to investment bank Evercore ISI, citing its industry contacts.

Memories of last year’s “false dawn,” when oil rallied to $60 a barrel only to crash in the second half of the year, also argue against any aggressive production hikes.

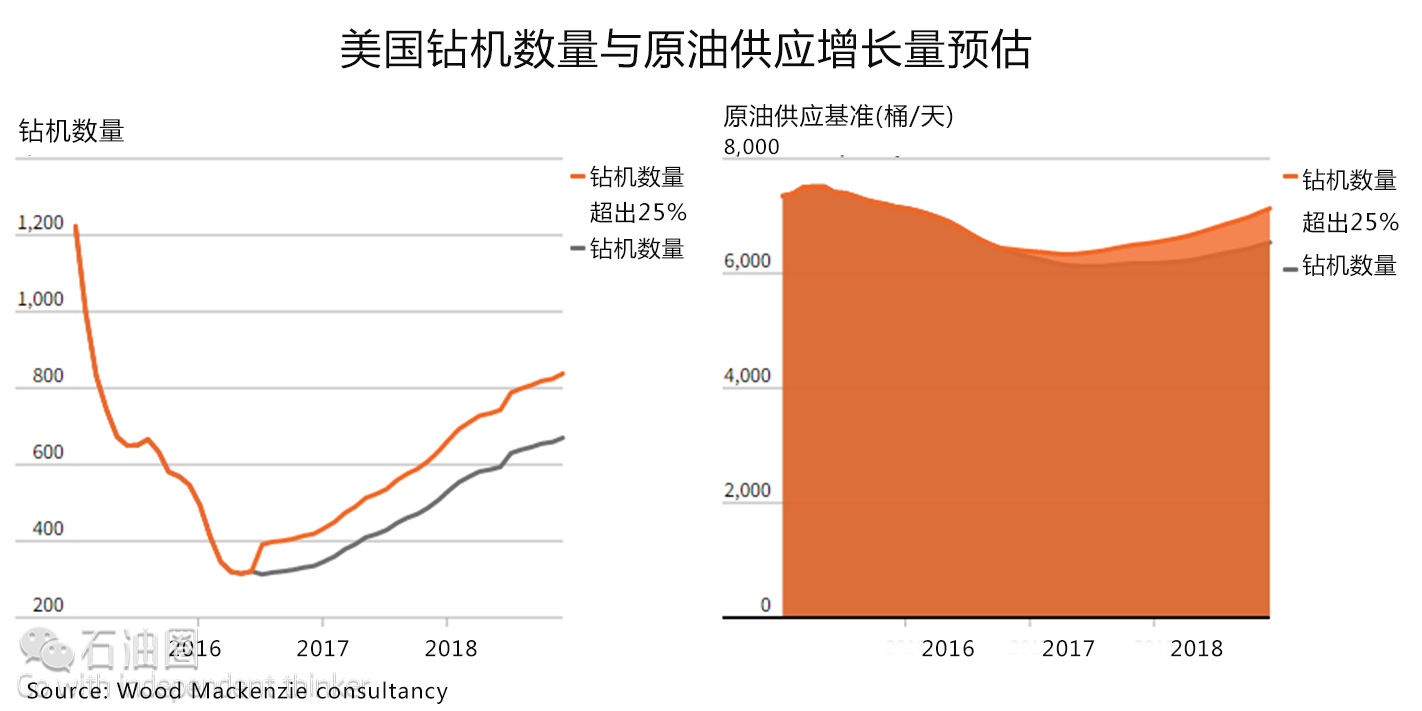

Then there are the uncompleted wells that can get finished quickly, unleashing up to hundreds of thousands of barrels per day of extra supply that could put the brakes on price gains. In fact, U.S. producers have been adding drilling rigs more slowly than in 2015 when they added 50 rigs in just two months in response to a sudden jump in prices, according to Baker Hughes data. Wood Mackenzie consultancy estimates drillers will add about 22 rigs by the end of the year, and 160 next year.

Yet Bill Thomas, chief executive of major shale producer EOG Resources, warned recently that producers could still end up drilling more than it made economic sense. “Our industry does have a bad habit of destroying capital,” he told an analyst conference. “It will be death by a thousand lashes, but at moderate oil prices, truly there’s a lot of the acreage being drilled in the U.S. that will never be productive.”

石油圈

石油圈