The only thing certain about any and all economic forecasts is that they are wrong. I don’t know why and don’t know in which direction, but be assured the published information will not be correct. There are just too many unknowns when predicting the future. The multitude of wrong predictions on oil prices in the past two years is but one example.

That said, modern commerce depends upon forecasts and therefore they proliferate. But for years economics has often been called, “the dismal science”. The old George Bernard Shaw quote goes, “If all the economists were laid end to end, they’d never reach a conclusion”.

This is in stark contrast to climate change forecasts for which “the science is settled”. It seems counterintuitive that a civilization which cannot predict the future price of oil can accurately forecast the weather with such accuracy and what the necessary political response is. Perhaps the oil guys should hire some environmentalists.

And so it goes with the latest forecast on future oil production by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP). In mid-June CAPP released its annual Crude Oil Forecast, Markets and Transportation study. It is actually pretty good news considering the current state of the industry because it shows continued production growth through 2030. Like previous forecasts it is most likely wrong, but it does provide some optimism about the future for the Canadian oilpatch.

CAPP writes in the prelude to its supply forecast, “Crude oil is one of the most important commodities in the world. Not only is it the dominant source of transportation energy now and for the foreseeable future, it has many other uses. It is a crucial raw material for the chemical industry, and in the production of plastics, which makes possible almost every item in our daily lives. CAPP is forecasting Western Canada crude oil production to grow by over 1.1 million b/d by 2030. After blending and including imported diluent volumes, this means over 1.5 million b/d of crude oil supplies need to be transported to refining markets.”

This must be what oil producing associations feel compelled to write in the face of a loud and growing anti-oil movement, one which increasingly espouses the view hydrocarbon fuels will soon be obsolete.

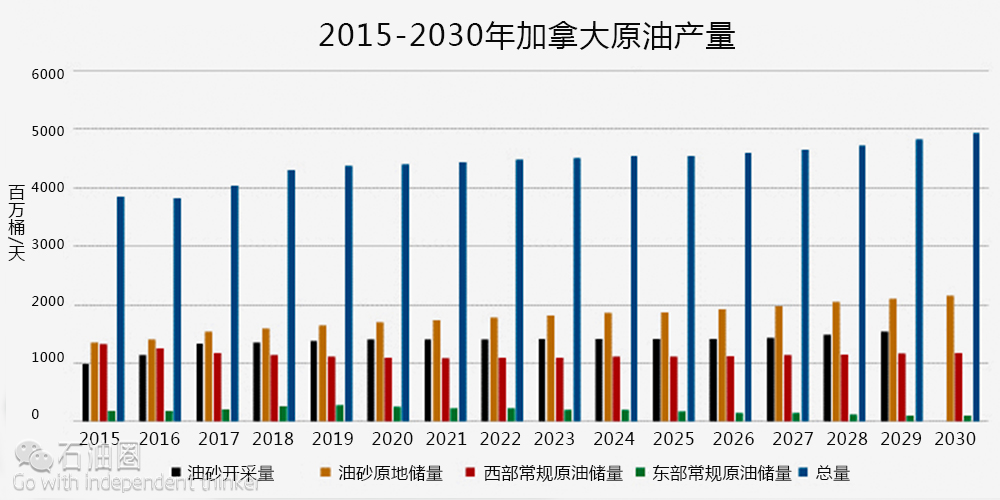

1) Total bitumen production is actually higher. The oilsands mining and in situ figures are for net bitumen production after upgrading.

2) 2) Conventional western oil production includes light and medium crude, heavy crude and natural gas liquids such as pentanes and condensate.

3) 3) Conventional eastern production is primarily offshore but there is a small amount of production from Ontario.

Over the 15-year period CAPP sees crude oil production rising by 1.1 million b/d from 3.852 million b/d in 2015 (actual) to 4.928 million b/d in 2030. Most of the growth will come from oilsands which will rise from 2.365 million b/d to 3.668 million b/d, an increase of about one-third. Western Canadian conventional production will fall nearly 200,000 b/d from 1.311 million b/d in 2015 to 1.167 million b/d in 2030. Eastern Canadian output will rise from 176,000 b/d last year peaking at 275,000 b/d in 2019 as new projects come on stream. Thereafter it will taper off to only 93,000 b/d by the end of the forecast period.

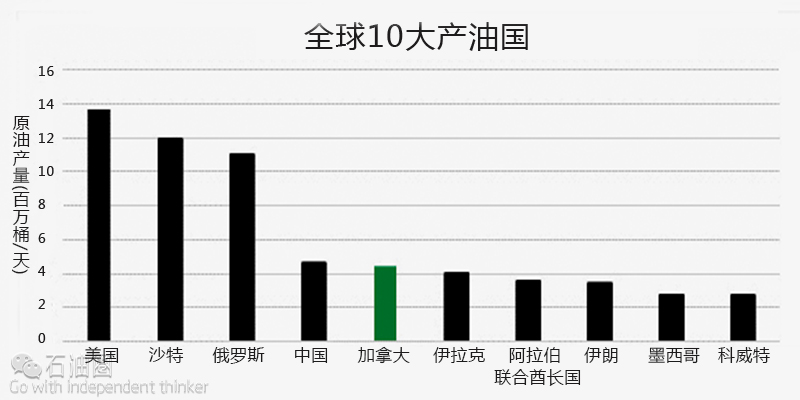

What is important about these numbers if correct is that Canada will remain a significant oil producer on a global scale. The following chart shows the top ten oil producing countries in the first quarter of 2016. They have changed somewhat since March (Iran may be a bit higher) but Canada is unlikely to be removed from the world’s top ten oil producing countries anytime soon unless non-oil alternatives make considerably more progress than is currently anticipated.

CAPP’s methodology for oilsands growth includes projects which are known or on the drawing board but which have not yet been completed. Imperial Oil, for example, has announced a couple of projects which are not yet underway. The primary source of growth will be increased production and efficiency from existing operations once the current round of major project construction is completed.

CAPP writes extensively about market access and how North America is and will remain the major market for Canadian crude. By 2017 western Canadian output will exceed existing pipeline capacity. CAPP wrote, “Canadian crude supplies (from the WCSB) are forecast to grow by 1.5 million b/d in 2030 (In this number CAPP includes bitumen diluent which is imported into Canada and must be shipped to markets as a blended commodity). Pipelines are the preferred mode of transportation to move this product but unexpected extensions in the regulatory projects have created new uncertainty around project timing. However, it remains clear that better tidewater access will be needed to reach growing global market outlets and capture full value for western Canadian supplies”.

To this end the full report carries an extensive survey of the array of crude-by-rail transloading terminals in western Canada which the report indicates must be utilized in the absence of new pipeline capacity. In previous presentations CAPP had included startup dates for various pipeline projects. Not this year.

CAPP makes no predictions on oil prices. It does, however, provide a comprehensive list of known and approved oilsands projects which are either in production or approved.

Hopefully, the future will unfold as presented above. It is great news for the oilfield services industry which provides equipment and services for all aspects of the business. Of particular interest is the size of the production maintenance sector which, based on production, will be 25 percent larger in 14 years than it is today based on total crude oil output.

However, this forecast is somewhat tempered from that of previous years because of the realities of the oil price collapse and the absence of meaningful new low-cost pipeline takeaway capacity. Such is the inherent risk in the forecasting game. In the 2012 CAPP crude oil forecast production in 2030 was predicted to be 6.2 million b/d, the major change being oilsands output of 5 million b/d compared to this year’s estimate of 3.7 million b/d. This 1.3 million b/d decline is the negative impact of the numerous projects which have been delayed or cancelled in the past few years.

On June 27, 2016 oil and gas forecasting and analytics company IHS Energy released its own forecast for Canadian oilsands production. In a Globe and Mail report IHS sees output reaching 3.4 million b/d by 2025, about the same as CAPP’s number if upgrading volume loss is not included. This is a million b/d increase in the next nine years, not the rate of growth service and supply had hoped for but hardly a sunset industry. IHS figures that since 2014 the capital cost of a new oilsands plant has fallen by $10 a barrel and thermal operations could now break even with crude at US$50 per barrel (full cycle cost, not just operating which is lower).

Forecast or not, much of the oil output growth in the next three years from 2016 to 2018 – 520,000 b/d – will come from projects that are for the most part already underway. As challenging as this market has been – compounded by the devastation of the recent wildfires – this is a great reason for the workers and companies supporting this industry to be at least modestly optimistic about their future. Oil prices have not risen high enough to spur this sort of production growth in any of the other major crude and natural gas liquids producing regions of North America.

For conventional light, medium and heavy crude and natural gas liquids investment and activity will recover with price. After four months of almost steady price recovery, recent events in Europe have set back the crude oil price recovery for the moment. But this is likely temporary. In its weekly report ARC Financial Corp. wrote about Brexit on June 28, 2016, “Brexit is unlikely to affect demand growth in a meaningful way; to the contrary it’s more likely to delay investment into new supply, which will lead to higher prices.” The thesis is turmoil in global capital markets will make it even harder for oil companies to raise capital which will, down the road, further pinch supply.

石油圈

石油圈