Pioneer had no idea it had the prime position in what might be the biggest oil patch in U.S. history.

In the fall of 2011, Tom Spalding, a slim geologist with salt-and-pepper hair, stood before the board of directors of Pioneer Natural Resources, an oil and gas exploration company, to make a presentation unlike any he’d made in his 14 years there.

Using two flat screens in Pioneer’s suburban Dallas boardroom, Spalding, the company’s vice president for geoscience, walked directors through the results of weeks of research. He and his team had explored for undiscovered oil in horizontal shales deep within the Permian Basin, a vast rock formation beneath West Texas. They had analyzed seismic data and core samples of 7,000 company wells as well as information on decades-old wells archived at the University of Texas. “When we first did it, we couldn’t believe it,” Spalding recalls. “We had to go back to check our measurements.”

He showed the board a schematic of 13 slabs stacked one atop another like something out of a Frank Gehry sketchbook. Almost every tier was splashed in bright red, signifying the presence of crude. Crucially, there was scant evidence of the saltwater zones that often dot such diagrams and can spell doom. It was all oil.

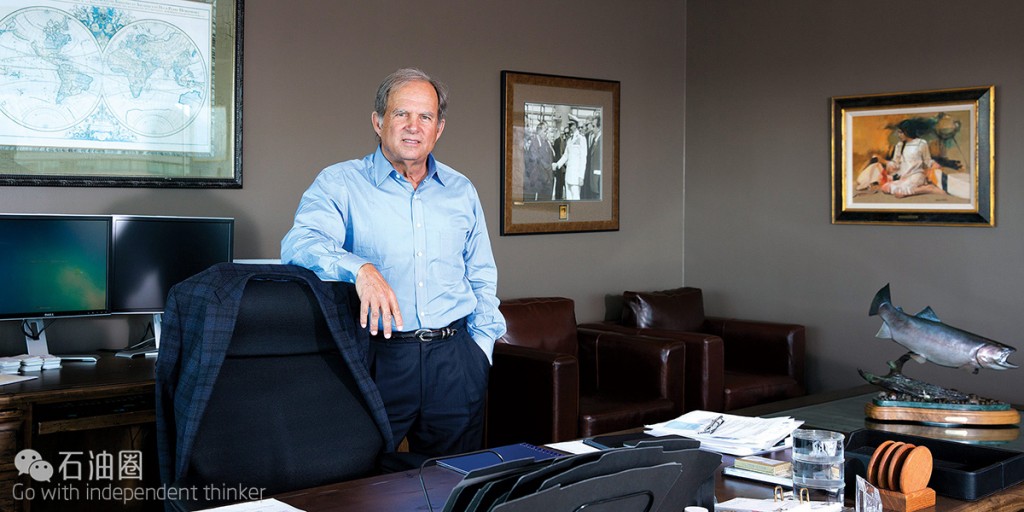

Pioneer’s chief executive officer, Scott Sheffield, watched with anticipation. He’d been drilling vertical wells in the Permian since 1979 with only modest success. After hearing his geologist, he ordered the drilling of two horizontal test wells.

Those wells cost four times what a vertical did, but wound up spewing seven times the crude. Sheffield called for more horizontals. He had the money to invest because he’d sold off seemingly sexier oil projects and avoided borrowing while other independent drillers were wagering yet again that oil prices would forever climb.

By 2015, Sheffield had stopped drilling new vertical wells altogether and diverted almost all of Pioneer’s effort and money into the Permian’s shale. All of which helps explain how Pioneer—a $26 billion company with less than a 10th of ExxonMobil’s market value, almost no oil fields beyond Texas, and the same boring CEO for more than 30 years—is now showing the world how to thrive amid the worst oil bust since the 1980s.

As crude prices have fallen about 60 percent since their most recent peak, in June 2014, investors have seen $1 trillion in value vanish. More than 40 oil-related companies have sought bankruptcy protection, and more filings are expected. Lenders are setting aside billions of dollars to cover losses. But over the last seven calendar years, Pioneer’s stock has risen an average of 34 percent annually, more than 10 times the rate of Exxon and Shell. In 2016 its shares are up 29 percent.

“Everybody looks good when prices are high,” says Michelle Foss, chief energy economist at the University of Texas at Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology. “Not very many companies look good when prices are lower.”

Pioneer has a huge presence in the Permian, with the rights to 800,000 acres and more than 20,000 drilling sites that could hold as much as 10 billion barrels of crude. Sheffield estimates the Permian shales in total could hold 75 billion barrels, second only to Saudi Arabia’s gargantuan Ghawar field. Pioneer’s good fortune is the result of a bunch of little, long-ago bets that added up to a big one. Sheffield bought most of the company’s Permian drilling acreage in the ’80s and ’90s, when the world’s oil giants were bolting West Texas for offshore and foreign plays. Sheffield kept it because it was low-risk and reliable. He had no idea those parcels one day would reside in what might be the biggest oil find in U.S. history.

Scott Sheffield personifies Pioneer just as he defies the stereotype of the Texas wildcatter. A 63-year-old with bushy reddish-gray eyebrows and a hint of his native Texas accent, he’s cautious and publicity-shy—the antithesis of the late natural-gas fracker Aubrey McClendon.

Sheffield attended high school in Iran, where his father worked for Arco. Sheffield was a petroleum engineer at Amoco in 1979 when his then-father-in-law, Joe Parsley, hired him at Parker & Parsley, a small independent producer in Midland, Texas, in the heart of the Permian Basin.

The Permian was once the mother lode of U.S. crude production. First drilled in the 1920s, it endowed Texas with a sway over global energy markets unmatched until the rise of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Parker & Parsley focused on a part of the basin named for Abner Spraberry, who owned farmland where oil was discovered in the 1940s. Sheffield made it his mission “to know the Spraberry backward and forward,” he says. Eventually he could rattle off the daily production rate of every Parker & Parsley well. The wells were unspectacular but consistent producers that promised to last for decades. Parsley lectured his son-in-law on the value of hanging onto such dependable assets.

Parker & Parsley’s co-founders sold their company in 1985 to a real estate concern. Sheffield was named president of its Parker & Parsley subsidiary. The major U.S. energy companies were shedding domestic assets to invest overseas. The middling Spraberry wasn’t economical for the big guys, but it was fine for Sheffield. He started buying drilling leases from Mobil, Exxon, and others.

Parker & Parsley broke away from its parent in the late 1980s and went public in 1991. Sheffield kept buying the Spraberry even as Wall Street yawned and experts proclaimed the Permian to be old news. “It had no sizzle,” Sheffield says. “That’s what analysts and investors told me.” But he viewed those acres as an annuity that would keep producing as the company tried riskier ventures. “He looked at it as kind of the breadbasket,” says Tim Dunn, then a top Sheffield lieutenant and now CEO of CrownQuest Operating. “He went against the grain and used it as a platform.”

In 1997, Parker & Parsley merged with Mesa, the company founded by T. Boone Pickens and later restructured by investor Richard Rainwater. The new company, Pioneer, moved to the Dallas suburb of Irving. Suddenly, Sheffield had a big gas field in Kansas and $1.6 billion in debt, five times what he had before. Not long after, oil prices crashed. Pioneer lost almost $1.7 billion from 1997 to 1999. After firing 300 employees, Sheffield vowed never to let Pioneer get so leveraged again.

Over the next decade, the company embarked on drilling adventures in Tunisia, South Africa, Argentina, Canada, and the Gulf of Mexico. By 2011, it was unwinding all of them, partly because of heightened political risk overseas. It was Texas (and a small stake in Colorado) or nothing.

At the time, crude was flowing from North Dakota’s Bakken field and gas from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus formation out of wells bored sideways, then fractured—or fracked—by blasting in water and sand to prop open cracks and let hydrocarbons out. Pioneer began to have some success drilling horizontally in a south Texas formation known as Eagle Ford. The company had plenty more places to drill to the northwest in the Permian. Only then were drillers realizing fracking could work there, too. Chevron revived its dormant Permian portfolio. Independents came, as well, including Apache, Diamondback Energy, Concho Resources, and Parsley Energy, named for Joe Parsley. It’s run by Sheffield’s son, Bryan Sheffield.

Pioneer’s advantage was a rich trove of data it had compiled on those Permian acres stretching back to the days of Parker & Parsley: logs from its own and others’ wells, warehouses of cylindrical drilling cores, and a database of raw numbers on rock porosity, density, and flow rates. Plumbing that information, Pioneer’s geoscientists could assemble a 3D subterranean map of how oil and gas flowed in the Permian. “We basically make treasure maps and put an X on where to drill,” Spalding says.

It’s a sunny March afternoon on a dusty plain 30 miles north of Midland. A brisk wind scatters tumbleweed and snaps the yellow caution tape snaked around a Pioneer rig drilling a fresh Spraberry well. The rig towers over ranch land owned by the Scharbauer family and leased by Sheffield in the late ’80s.

In a control room 40 feet up, Executive Vice President J.D. Hall peers over the shoulder of a young man using a joystick and a bank of monitors to help maneuver a drill bit through dense rock 2 miles underground.

“You’re looking for the sweet spot,” says Hall, a bespectacled petroleum engineer in jeans, work boots, and a white Pioneer hard hat. “Then you gotta stay in it.”

Pioneer’s geologists have determined that this bore needs to twist—or, as Hall puts it, “porpoise”—through an oval of rock 50 feet across and 30 feet from top to bottom. Once it’s done, the rig will be shifted 45 feet to drill a second well, then moved over for a third.

Fracking has continued to evolve. Drillers are now extending bores laterally as far as 10,000 feet. This enables the installation of more “stages”—as many as 35 on a single bore—at which the rock is fractured, or “stimulated,” in the jargon. In effect, drillers build a series of miniature wells along the horizontal bore, each draining out petroleum. Depending on the peculiar geology of the rock, producers also vary the types and amounts of sand and water used and how hard it’s pumped in. Pioneer in particular has focused on spacing separate bores close enough laterally that between them they create complex fracture networks that yield more oil and gas. If the bores are too far apart, they can leave hydrocarbons behind; too close and they can interfere with each other, reducing the flow. “There’s no one way to do it,” says Allen Gilmer, CEO of Drillinginfo, an Austin oil and gas analytics firm. “The difference between a good frack job and a bad frack job might be 50 percent of production.”

At the three-well drilling pad on the Scharbauer lease near Midland, the bores will do their porpoising 650 to 800 feet apart. Pioneer will apply what it learns from seismic testing and production results to the next site nearby, expanding or shrinking the distance between bores. Then it will keep spreading the knowledge incrementally across its 20,000-plus Permian drilling sites.

Pioneer spends, on average, about $8 million to complete a well. In a March investor presentation, the company said its cost to drill and frack each 12-inch length of a well dropped 30 percent in the past year, to $905. At the same time, production from those wells jumped more than 50 percent. The cost declines are expected to slow, but Pioneer last month lifted its 2016 target for production growth without any spending increase. Such efficiencies have made it possible for the company to amass cash with crude prices as low as $35 a barrel. Pioneer’s cash reserves rose to $1.61 billion in the first quarter of this year, up from $383 million a year earlier.

The company, meanwhile, is spending a lot of money now in the belief that oil prices will soon rise. Not everyone thinks it will pay off. Criticizing shale drillers at the Sohn Investment Conference a year ago, David Einhorn singled out Pioneer, in which he has a short position, as the “Mother-Fracker.” Einhorn, president of Greenlight Capital, argued that Pioneer lost $12 for every barrel it developed over the previous nine years. “That’s like using $50 bills to counterfeit $20s,” he said. Pioneer’s shares fell almost 2 percent that day. Then the market reconsidered—the share price has nearly recovered even as oil plunged from $63 a barrel to as low as $26. Pioneer’s stock for the past year has outperformed its peers by more than 50 percent.

A Pioneer pad site near Midland

Daniel Katzenberg, a senior analyst at Robert W. Baird, says investors aren’t worried about profits as much as production. Quarter after quarter, the output of Pioneer’s new horizontal wells has exceeded expectations, and that’s why the stock price keeps rising. “What the market sees is that they’re sitting on one of the most attractive and economic resource plays in the world,” says Katzenberg. “Pioneer is tasked with proving their acreage is as good as the hype.”

Sheffield doesn’t get out to West Texas that often. But he has brought Pioneer home, and he bristles a little at the suggestion that he’s just lucky to have those acres. He invokes Parsley, who died in October at the age of 86. “You shouldn’t sell long-life assets,” he says. “The best decision we ever made was never to sell the foundation of the company.”

石油圈

石油圈