Expanded use of 3D printing could transform oil and gas operations, but challenges remain to fully utilizing 3D printing’s potential.

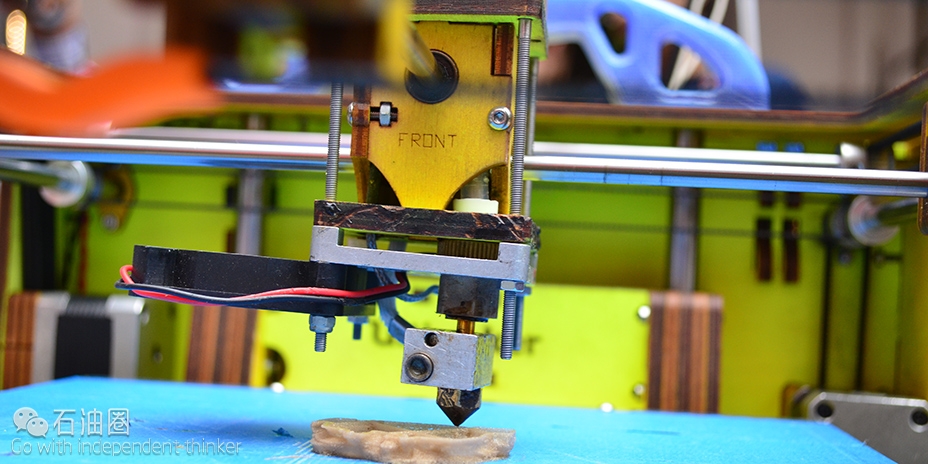

3D printing – or the process of making physical objects from a digital model using a printer – has been around for decades, but a number of industries, including oil and gas, are now exploring ways that 3D printing could enhance product development.

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, rapid prototyping or rapid manufacturing, has made headlines in recent years as the convergence of increased technology sophistication, lower equipment costs and far greater diversification of 3D printable materials. This has allowed 3D printing to move into the mainstream manufacturing and consumer market, according to a 2014 Accenture report on 3D printing’s potential for the oil and gas industry.

The expiration of a number of 3D printing technology patents has allowed more companies to enter the 3D space. The move by a number of industries for 3D printing applications beyond non-functional prototyping, surge of technology start-up companies, and availability and quality of printable materials, also have contributed to the major surge of interest by industry in 3D printing, said Lux Research Analyst Anthony Schiavo in an interview with Rigzone.

The aerospace and dental industries have both used 3D printing to produce parts. Key advantages of 3D printing include the ability to make smaller parts or parts with complex shapes or to reduce waste of high cost materials, Schiavo said.

Oil, Gas Companies Exploring 3D Printing

GE Oil & Gas started development activities on Additive Manufacturing (AM) Technology about five years ago, said Massimiliano Cecconi, materials & manufacturing technology leader for GE Oil & Gas’ system engineering and advantaged technology, in a statement to Rigzone. This development was further accelerated nearly three years ago with the installation of the first Direct Metal Laser Melting Machine (DMLM) in GE Oil & Gas Additive Manufacturing Laboratory in Florence, Italy.

“Since then, the laboratory has grown its capabilities thanks to the addition of two additional machines for the development of turbomachinery components and special alloys,” said Cecconi.

Collaborations with GE Aviation and GE Global Research Center have significantly accelerated the development of the technology. Capabilities have been significantly accelerated thanks to the creation of a new GE Oil & Gas Additive Manufacturing Lab in Bangalore, India.

GE is pursing three main activities in its lab. The first is fast prototyping of parts supporting new production introduction. This technology has enhanced GE’s ability to rapidly test several design concepts significantly shortening the development cycle, according to the company’s Fastworks approach, a methodology developed by GE to increase customer engagement and accelerate new products introduction time-to-market.

One example of this approach is the AM development of the burner for the new NovaLT16 gas turbine, said Cecconi. Four different design concepts were manufactured using DMLM and rapidly tested into our full-scale combustion rig, substantially reducing the development and validation cycle of these parts by over 50 percent, said Cecconi. The selected design of the fuel burner was successfully produced in initial rate to equip the first NovaLT16 engines and positively tested with it. GE also is leveraging its capability to generate complex geometries almost for free.

The company is using this capability to redesign gas turbine combustion components with the introduction of innovative shapes and geometries, enhancing performance and emission reduction. “The novelty of the technology requires a transformative mindset approach for our design engineers that are now able to move in an enlarged design space with increased geometrical possibilities, compared to traditional manufacturing technologies like investment casting,” said Cecconi.

The possibility to print a component in a single piece instead of multiple parts to be brazed, welded or bolted together is an additional benefit in terms of simplified manufacturing process and assembly operations. “Compared to the traditional approach, our customers will also benefit from more frequent technology upgrades on their fleet due to the velocity of the new solutions introduction this technology allows,” said Cecconi.

The third level of printing that GE is exploring is the manufacturing of spare parts for installed fleets. “Our customers complain about the need to keep relevant stock of spare parts in their warehouses to assure limited shut-down periods for their equipment and plants,” said Cecconi.

“The AM-3D printing represents a paradigm shift, thanks to its ability to shorten production cycles and to bring production of hot gas parts of old gas turbine models like the Frame 3. To validate the assumption, it is possible to produce these parts quickly and with the same, or even better quality, than the original parts.”

While the initial development effort was mostly focused on turbomachinery components, GE is now in the process of extending its experience with 3D printing to its other produce lines such as subsea. “We have defined a challenging roadmap to leverage AM capabilities for valve parts, aiming improved design and shortened procurement,” said Cecconi.

In November 2014, GE Oil & Gas announced it would start operations of a new GE Additive Manufacturing Plant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This plant will further accelerate knowledge-sharing and expertise across GE’s different businesses, including oil and gas. “In summary, GE Oil & Gas is transitioning the technology from development and small rate to full production rate of components for turbomachinery applications,” said Cecconi.

“Opportunities to apply the 3D printing technology are mostly still undiscovered, requiring at the same time to reinvent the way we design and produce parts.” Oilfield service company Halliburton also has been using 3D printing across its different business lines, including completion tools, wireline and perforation tools, testing and subsea, and in its Sperry Drilling and drill bits and services lines, a Halliburton spokesperson told Rigzone.

Prototyping a part through 3D printing can take a couple of days, but the process is still faster compared with traditional prototyping processes, said Allen Zhong, research and development manager with Halliburton, in an interview with Rigzone. Parts with complex geometry also can be created more quickly with 3D printing. The limitations of traditional manufacturing mean that complex parts have to be broken into many components in order to machine the inside. By using 3D printing, parts can be combined to reduce the number of components. For example, a flow control device built through traditional manufacturing would have be built in two parts and then welded together; through 3D printing, the device can be printed in one part.

Challenges of 3D Printing in Oil, Gas Industry

While the oil and gas industry is no exception to industries looking at how they can use 3D printing, Lux researchers see limited potential for 3D printing in the oil and gas industry beyond the prototyping phase. High concerns about the liability and reliability of parts made through 3D printing will slow the adoption of 3D printing in the oil and gas industry. Schiavo pointed to the steep learning curve in the aerospace industry, with more than a decade needed to develop their internal processes to ensure quality and reliability of parts made in 3D printing.

Accenture does sees potential for 3D printing in oil and gas, but the downturn in oil prices means that companies will want to save money in 2016, and likely delay plans to explore 3D printing. 3D printing is a research and development agenda for how to save money in five to 10 years, said Brian Richards, North America Energy Innovation Lead for Accenture, in a statement to Rigzone.

“People are thinking about non-critical parts, as well as customized tools as a starting point, but issues remain around liability if a part were to fail, as well as who owns the intellectual property,” said Richards.

A new type of 3D printer and materials for 3D printing would need to be developed to operate in the high-pressure, high-temperature environments where energy companies often operate, Richards said. Software also is needed to address the computational challenges of fabricating complex surfaces and intricate designs, but Accenture has not seen oil and gas make progress in this area.

Barry Calnan, 3D printing manager with 3D-Printing Solutions, part of well control and rig equipment consulting firm Subsea Solutions LLC, said that the materials available for 3D printing also would need to be certified by the oil and gas industry, in the same way that the aerospace and motor vehicle industries has done, to make them usable. Subsea Solutions uses 3D printed models as part of its training courses, allowing students to hold, take apart and reassemble components of equipment such as a blowout preventer.

Intellectual property considerations are another area of concern, especially for operators, as much of the intellectual property involved in these components belong to third parties.

“There isn’t a single broker in the market – in the same way that iTunes is a broker in the music market – to bring together different companies and put them all under a common intellectual property framework,” Richards noted.

While there are a number of issues, 3D printing has interesting potential for offshore. Lux researchers see greater potential for its use for offshore versus onshore due to the remoteness of offshore from machine shops and skilled labor. One of the long-term holy grails of 3D printing is the ability to make parts on site as needed, instead of having to fly in parts when something breaks, Lux analysts said. In the case of a drilling rig, this would entail having material and printer to make parts. Creating a part through 3D printing can take between six and 24 hours. While this could reduce the lead time for replacing a part on an offshore rig, a drilling rig doesn’t have all of the quality control and inspection tools of a factory.

“In general, anywhere you have complex parts that use expensive materials and are made in small batch sizes, 3D printing could be a solution,” said Schiavo.

In its 2014 report, Accenture touted the ability to manufacture tools onsite at remote locations as a way for oil and gas companies to better manage their supply chain operations. For oilfield service companies, there is an opportunity to sell the digital representations of their tools or a license to print parts – much like a music label sells this right to iTunes, said Richards.

“However, it is not expected to be ‘material’ to oil and gas revenues in the near future, or less than five years. Another area of opportunity for companies is to look at parts that were made by companies now out of business, and use 3D printing to extend the useful life of an asset.

How should oil and gas companies approach 3D printing beyond the prototyping it has done for years? Accenture advised in its 2014 report that companies should begin by building models to become more familiar with the current state of the technologies, as well as creating strategies that target arears of the organization where this technology can provide the most value.

“Close collaboration with field workers will help companies understand which parts could be 3D printed, as well as how it can be applied to maintain and/or replace equipment as it becomes legacy.” Operators also should begin working with suppliers outside their organizations to see how they plan to use 3D printing in their supply chains in the future.

“In upstream operations, control and visibility over the supply chain will be crucial to making proactive, data-based decisions on where 3D printing technology can be applied most effectively,” said Accenture in the report. “The importance to achieving success may lie in verifying a smooth transition to a digitalized supply chain without compromising existing structures.”

Accenture also is encouraging suppliers and service companies to use 3D printing as part of their portfolio of cost savings measures, said Richards. “The value won’t be ‘significant’ compared to other levers that are more mature, but it can lay the foundation for greater understanding around the potential use cases and value.”

3D Printing Calls for New Approach in Engineering Drawings

Calnan said that 3D printing is more than just reproducing parts that are already being created in a cost-efficient way. But increasing the number of ways that 3D printing can be used in oil and gas means that old school engineering drawings would need to be translated into modern design, or modifying existing design concepts into designs not envisioned when the parts were designed using standard manufacturing technologies, said Calnan.

Part of the issue also is changing engineers’ mindset of current manufacturing standards and limitations. Calnan cites the example of a group of engineers that he had presented to on the concept of 3D printing. While they found it interesting, the consensus was that it would be impossible to use 3D printing. This is very understandable, as 10 years ago, the main focus of engineering was to know the rules and make sure everything was engineering to meet the standards and make things work well and safely.

“The downside of current manufacturing standards and limitations is that they prevent innovation and curiosity,” Calnan noted. “This goes back to ‘It’s the way it’s always been done’,” said Calnan. “A machined part is smooth and shiny and a printed part may have a rough look, but both do the same thing. It’s more a preference than a functional issue. But with the printed part, you have the ability to create anything.” But Calnan believes that the use of 3D printing in oil and gas will grow as the existing workforce retires and is replaced by students coming up in the school system who have been exposed to 3D design and printing from the beginning. Calnan hopes that 3D printing can allow oil and gas tools and equipment to be reimagined in new, more efficient ways, a goal on which major oil and gas companies would have to take lead. Doing things the same way that they’ve always been done and expecting to innovate is just crazy. “In a downturn, you need to leverage the people you have to create better products in a better, and more cost effective way.”

石油圈

石油圈