Reservoirs prone to producing sand along with oil and gas can cause a lot of headaches for operators. For starters, the sand can damage the equipment. It can restrict the flow of oil. At worst, eroding formations can collapse and damage the wellbore. The standard response to the sanding issue has long been to place sand screens downhole.

“But that doesn’t really solve the fundamental problem,” says Frank Chang, petroleum engineering consultant at Saudi Aramco’s Exploration & Petroleum Advanced Research Centre in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.

Such equipment can clog simply by doing its job, and there is a secondary drawback – it can slow oil production.

A few years ago, Chang and his colleagues began thinking about better methods for producing in unconsolidated reservoirs.

“We wanted to be more proactive,” Chang says. “We wanted to see if we can glue these sand grains together, so they are consolidated, so the fluid will flow, but the sand will stay there.”

Keeping the sand in the reservoir removes the need for expensive sand screens in the wellbore, he adds.

In their research, launched in 2015, Chang and Rajendra Kalgaonkar, a polymer scientist with Saudi Aramco, looked at various methods of keeping sands in the reservoir and out of the wellbore.

Resins seemed a possibility and were available from service companies, Chang says, but while an epoxy resin did keep the sand in place, it caused a larger issue. The resin filled up the pore spaces and blocked the flow of oil, which he says is the main issue with existing products in the industry.

“It prompted us to regroup and focus on a new kind of chemistry,” he says.

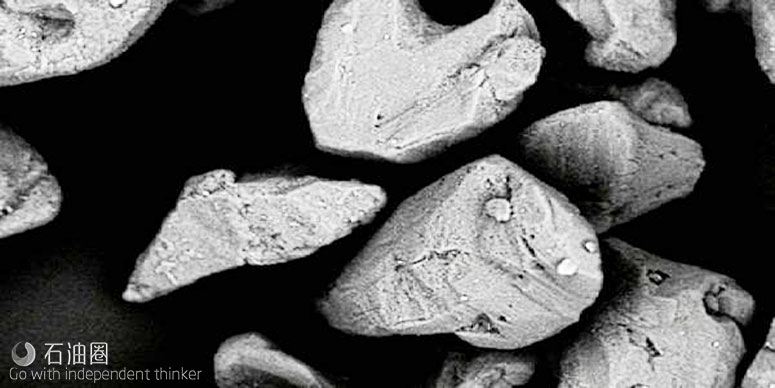

The search was on for something that would have an affinity for the grains of sand, but not for itself, so that it would not come together and block the pore spaces. Ideally, Chang says, such a material would spread out in a thin sheet upon contact with the grains of sand.

The pair turned to nanoparticles, mostly with silicate bases, when the quest first began. While they are still fine-tuning the application process, the basics are in place, Chang says.

The chosen nanoparticles have a positive charge and can self-assemble via electrostatic attraction over the unconsolidated formation of negatively-charged sand particles to form a layer of consolidating material. The self-assembling nanoparticles cure at reservoir temperatures and form a thin layer of hard gel around the sand particles. The sand grains are cemented together, while the pore spaces remain clear for oil production.

“The material we would like to develop is basically a liquid-to-solid sand consolidation chemical that, when we inject it into the formation, it covers the sand grain only, without filling up the pore space. So, when it sets, the sand grains are held together but the hydrocarbons can still flow into the well without additional restriction,” Chang says.

The nanoparticles can be delivered through a single step — one “pill”—during a coiled tubing injection, he says.

“We’re still fine-tuning how to put it in the right place,” Chang says. “The thicker the zone, the more difficult it is to put chemicals in the right places to achieve full coverage.”

He says extremely thick formations or extended horizontal wells could be a limitation until reservoir engineers have a better placement mechanism for the nanoparticle treatment.

“We still have work to do. We’re still far away from our dream,” he says.

A field trial could happen in the next couple of years. The next steps for the technology include optimising the nanoparticle material so it retains its affinity to the sand grains but does so in a thinner layer, he says.

“To make it thinner, we have to control the additives. To make it set from a liquid, we need an activator with key nano material,” Chang says.

Chang and Kalgaonkar are fine-tuning the chemistries and synthesising new materials.

“We’ve always had the goal,” Chang says. “We believed, engineering-wise, that this performance is what was needed. We just set out to look for products that give us that performance.”

石油圈

石油圈