The long horizontals and extensive fracturing typical of many North American shale wells have made drilling and completions more complex, but technology has allowed operators to reach their targets much faster and brought a dramatic decrease in drilling costs.

“I think right now our industry is this extraordinary story that’s not being told. It’s amazing that we’re all still in business right now,” says Sam Noynaert, assistant professor in the department of petroleum engineering at Texas A&M University.

The reason is speed, he says. Wells being drilled in the Permian, Eagle Ford and other shale plays are coming in at fractions of the time they took to drill three years ago.

“They’re the same wells, often with longer laterals, with larger frac jobs, but because we’re drilling faster, it’s essentially keeping the industry afloat,” says Noynaert, a former drilling and completions foreman and engineer who still carries out some consulting work as an operations engineer.

“If you understand where that geologist is coming from, the drilling engineer can help the geologist with what they’re trying to do.”

—Sam Noynaert, Texas A&M University

As the operations teams are drilling the wells faster, they are also required to geosteer them faster, which can be a problem.

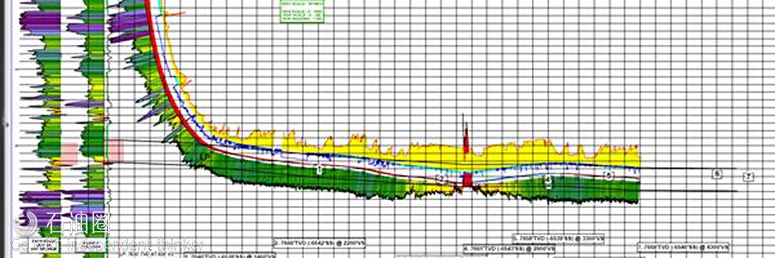

Stratigraphic geosteering – drilling and keeping a horizontal wellbore in a specific layer of the earth – sometimes targets a window as narrow as 1.5 metres.

Keeping the wellbore in the pay zone requires co-operation among drilling engineers, the well site team and the geologists who specialise in geosteering.

“These three parts of the team are all trying to work together,” Noynaert says.

The task is complicated enough without bringing into consideration the cultural differences driven by job performance metrics.

The geosteering professional is often measured on how much of the wellbore is within the pay zone, while the drilling engineer and well site team are typically rewarded for bringing a well in under the estimated time and cost to drill.

While the teams each have a common goal of drilling a productive well, the job drivers “are very different metrics, and those are usually at odds with each other”, Noynaert says.

“They’re working for the common good, but they’re still at odds with each other.”

In many ways, the groups speak different languages and do not understand the difficulties inherent in the other groups’ responsibilities.

The geosteering professional may not be conversant in the basic mechanics and physics of drilling, while a drilling engineer who makes decisions based on precise measurements may feel lost in the woods with the inherent uncertainties of a geologist’s work.

“While we understand there is uncertainty, we kind of just want a single, specific answer,” Noynaert says.

Ambiguous data

Raymond Woodward, president of BHL Consulting and BHL Boresight, says most geosteering issues stem from misunderstandings and misapplications, or too much faith in various technologies, while about a third boil down to workflow and work space cultures.

Many factors complicate a geologist’s job when it comes to geosteering. One of the biggest reasons for uncertainty about how the rocks and reservoirs exist below the surface is that there is no direct view or direct measurement of the subsurface until it has been drilled, he says.

“You just don’t fully know until you drill a hole in it. God alone can see what’s down there, and he’s not talking,” Woodward says.

“As a geologist, I love seismic data — I’ll take all the seismic data I can get. It’s understanding its limitations and avoiding the potential pitfalls,” he says.

“Every pre-drill geologic model is an incomplete and invariably defective prediction. It’s only a question of how incomplete and how defective.”

Sometimes, Woodward says, old vertical wells in mature areas are simply not where the maps say they are. Sometimes interpretations and interpolations are flawed.

“There are problems in interpretation. The saying is, if you give five geologists all the same data, you’ll get six different opinions about what’s down there and where to find it.”

Further, he notes, not all data are equal. Measurement and logging-while-drilling data are not always “gospel data” and cannot be considered as trustworthy as wireline logs, he says.

“If you use dubious data you get dubious results.”

Clouding the issue is that the explosive demand for geosteering capabilities means some who are carrying out the function have scant or no formal education in the principles of geosteering, he says.

Hindsight

Noynaert compares geosteering to driving a city bus that’s 60 feet long but with the steering wheel at the back rather than in front. In geosteering, the drillbit is at the front and the measurement tools at the back.

“You don’t realise you’ve run off the curb until the back of the bus crosses the curb,” he says. “You’re not looking forward out of the windshield at all. You’re looking backwards.

“The only data we have is where we’ve been. We don’t know what’s ahead of us. We’re steering the bus from the back, looking backwards.

“The geologist can catch a lot of grief from drilling engineers for appearing lost.

“They just don’t see where they are until 60 feet later. There’s uncertainty in interpretation and measurements,” Noynaert says.

Similarly, the drilling team and rig team may not see a reaction from the bottomhole assembly until about 60 feet later, he adds.

“This is the reality of geosteering,” he says. “It’s a complex thing we do. We steer these wells and keep them in zones in spite of ourselves.”

As Woodward puts it: “No matter what technology is involved, at the surface or downhole, geosteering is a geologic interpretation, period.

“That’s what it is. The geosteering interpreter’s work assumes the well path is where we think it is, but for a host of reasons, those surveys are never as accurate as they appear. Ever.”

Woodward calls positional uncertainty an “unpleasant topic” that nonetheless must be addressed.

Geologists tend to live in the world of uncertainty, while engineers are more used to “reducing everything to precision in an Excel spreadsheet,” he says.

“Not all engineers fully integrate this business of directional uncertainty in their thinking. They get frustrated when the geologist says, ‘we thought we were going to be drilling at 1.5 degrees down, but now we need to drill at two degrees down’.”

Horizontal drilling plans are based on pre-drill models, he notes. But “geosteering says, ‘this is where we get off the plan, and here’s why’. This is a source of frustration to the engineers, who just want to get it done. They don’t want a geologic treatise. They just want an answer.”

Opposing forces

If the drilling experts understand and accept a range of uncertainty in targeting, they can better plan their roles in the drilling operations, says Noynaert.

A geologist may respond to incoming measurements from the bottomhole assembly and demand a target change, which will result in “all sorts of complaining” from the drill site, he says.

“The geologist wants to know why everyone is so upset — they are simply trying keep the well path in the pay zone.

“The drilling engineer wants the geologist to know that target changes can result in an undulating wellpath, which can impair drilling efficiency.

“The three fundamentals of drilling that geologists need to know and understand as the unconventionals industry goes forward are torque and drag, the basics of directional drilling, and hydraulics,” Noynaert says.

Torque and drag refer to forces involved in moving pipe in and out of a well. Undulating well paths create more friction across the entire drillstring. The higher the torque and drag, the harder it is to steer the well.

“If a geologist is constantly steering up and down, trying to figure out where they are and stay in a hard-to-find zone, they’re doing exactly what they were asked to do.

“But the consequence of that is it makes the drilling and operations aspect that much more difficult,” Noynaert says.

“It becomes a vicious cycle, as oversteering makes future steering harder… It can take longer to drill a given foot of rock.”

In terms of directional drilling, geologists often underestimate how difficult it is to make sudden significant alterations in a well path.

For example, he says, a team is trying to land the well when, unexpectedly, “the geologist says, ‘I’m not sure where we are, let’s come up 20 feet’, and there’s this explosion of email and curse words from the drilling side. And the geologist says, ‘I don’t understand what you’re complaining about’,” Noynaert says.

“You don’t instantly transport yourself from A to B. It takes you some time to get there. The tools can only do so many things. There are some physical limits to changing direction.”

Learning experience

The limiting factor in extended reach and horizontal wells is beginning to change from torque and drag, Noynaert says, to hydraulics and the ability to circulate fluid without breaking something on the rig or damaging the formation.

“As these laterals get longer, this is something geologists are going to hear more and more about,” he says.

There is no clear-cut answer or solution to the problem, he notes, although he believes some basic awareness of the motivations of colleagues on other teams will help, as will understanding the consequences that decisions in one discipline will have on the others.

“Just having the understanding, which sounds touchy-feely, helps the process quite a bit. If you understand where that geologist is coming from, the drilling engineer can help the geologist with what they’re trying to do,” Noynaert says.

Training is crucial — not just in basic skills, but in improving cross-disciplinary understanding. Noynaert once brought a geosteering company into his drilling engineering classroom to give a short course.

For every example the geosteering professionals presented for interpretation, he says, “I got it wrong every time. I’d never tried it for myself, put myself in their shoes.”

The training was an eye-opening experience.

“It further drove home what I knew from experience – that the solution to improving a geosteering team’s performance is not with a new tool or logging technique.

“Instead it is the more fundamental and often difficult to solve aspects such as knowledge gaps, awareness of team members’ motivations and performance metrics,” Noynaert says.

If the whole team is working from a point of understanding and knowledge of the other group’s goals and limitations, he says, it is more likely to agree to sacrifice a little to bring in an overall successful well.

Another possible solution relates to determining who has final say over how and where the well is drilled.

“The management sets up the circumstances,” Woodward says. “It is sometimes difficult for the working engineers and geologists to overcome, but it is possible.”

He cites an example from the mid-1990s, when he was employed by Sonat Exploration as a geologist working in the Austin Chalk.

That operator put the drilling engineers, the geosteering professionals, and the well site personnel all on the same team.

“We had to sink or swim together. It wasn’t a circumstance of engineer versus geologist or vice versa. There was a strong organisational or cultural understanding that we would all succeed or fail together,” Woodward recalls.

“What resulted was there was a lot of motivation for us geologist types to educate the engineers and vice versa.”

Collaboration, Noynaert believes, is key for successfully and quickly drilling a horizontal well in the pay zone. Alone, each area has its own “cool area of expertise” but “we can’t do it on our own, and it is significantly better with everybody’s input”.

石油圈

石油圈