At its most basic, a chemical tracer allows operators to see the flow-back from each stage of a well.

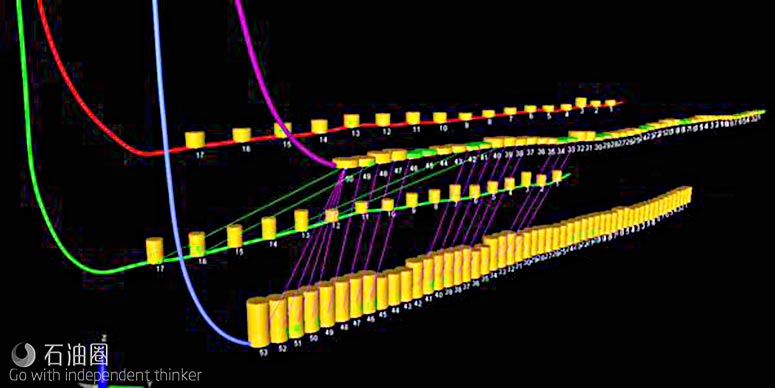

In an unconventional well, which may have four dozen or more stages, operators can find this quantitative measurement useful.

“Putting tracers in the well is neat, but I want a better well. I want to make money from it. I don’t want to do it just because I like science,” says Dave Bucior, Tracerco’s Reservoir business development manager.

“It’s nice to say that I got 10% of the oil from stage five and 20% of the oil from stage seven, but I want to know why stage seven gave me 20%, and why stage five gave me 10%.”

Tracers provide correlation between the stage production and geophysical data about the well, and operators can use the ever-increasing understanding about their reservoirs to create better plans for future wells and fields.

Chemical tracers are not new to the oil and gas industry. They have provided information about reservoirs for about half a century.

From the outset, the pattern tended to be a production well surrounded by injection wells, whereby a different tracer was placed in each injection well to determine how long it took to reach the production well.

As unconventional wells gained in number and increased in length – and regulations to protect the environment became more stringent – new technology had to evolve that could provide the information operators wanted about their wells, such as whether the stimulation of a stage was effective and whether the frac stage placement was correct.

About seven years ago, Tracerco developed and patented a tracer technology that would provide insight as to where in the reservoir oil was coming from.

Bucior says the company created a tracer capable of forming an emulsion with frac water, and due to its high solubility in oil or gas move across when in contact with native hydrocarbons in the reservoir.

The tracer enters the well’s fracture matrix via the stimulation fluid. When the well flows, the water comes out of the well first, followed by the oil or gas. The oil or gas carries the tracer back to the surface.

“We put a different tracer into each stage and sample the oil or gas at the top of the well when it’s returned,” Bucior says.

“We measure the concentration of oil or gas tracers in the samples and assign how much oil or gas came from each stage based upon the amount returning over a given time period.”

Tracerco’s new tracer technology, which the company refers to as Tracer Production Log, allows operators to track the water, oil and gas phase flow from each stage in a well.

“If I understand what I produced, I can then look at the assumptions I made when I drilled and stimulated the well and validate whether those were accurate,” he says.

An operator can then compare that tracer feedback with logging and production data.

“Whatever data they have and whatever decisions they’ve made about the well, the tracer technology today provides a method to evaluate how well they did when planning, drilling, completing and stimulating.

“The more they know and more they refine it, the better they’ll produce in the future,” Bucior says.

This data can tell them how close together to drill future wells, for example.

“If they drill wells too far apart and the fracture matrix doesn’t connect, then they’re leaving untapped hydrocarbons in the ground, but if they overlap too much, they’re drilling too close together,” he says.

“If we see tracers in one well and it also turns up in the other well, we can prove connectivity. By seeing how much returned from the parent well and how much came from the sister well, we can then begin to understand how much the fracture matrix overlaps.”

How long a tracer remains in the reservoir depends on the well. If a stage does not produce oil, the tracer will remain static in the ground. The higher the flow rate from a stage, the quicker the tracer comes out of the reservoir.

It is also possible to determine just how much tracer has been recovered from an individual stage.

Bucior says lengthening laterals in the unconventional plays mean more unique tracers are required.

“Five years ago, 15 tracers were all that was needed, because wells would be typically 15 stages in design. Today, 50 is common, and 70 stages is not completely unheard of,” he says.

“We’re on a never-ending quest to identify new tracers and bump that number up.”

However, identifying new tracers is not a simple matter. To be considered, a tracer must be a chemical that is non-native to the reservoir, it must not cause any changes in the reservoir, and it must not be altered by the reservoir or absorb into the geology within the reservoir. It must also have no detrimental environmental properties.

Sometimes there are misconceptions about how tracers work.

“Some people want to know what isotope we’re using. We’re not using radiation or stable isotopes. We’re using chemicals at such low levels that you couldn’t even detect them if you don’t know how,” he says.

Tracerco, which stopped relying on radioactive tracers nearly two decades ago, uses chemical compositions that are detectable in the production stream at a rate of parts per trillion.

“Every tracer we use has to be environmentally friendly,” Bucior says. “The tracers we use are carried in an environmentally-friendly solvent.

“The active chemical tracers have undergone scrutiny by the likes of the US (Environmental Protection Agency) to ensure that they meet requirements under the Toxic Substances Control Act programme.”

石油圈

石油圈