There are recent signs of life in the exploration sector, with as many delayed projects getting funding during the first half of 2017 as in all of 2016.

A report from consultancy Rystad Energy tempers that superlative by describing the jump in the number of delayed projects getting a final investment decision (FID) as “apparent positive momentum.”

On the upside, it reported 17 delayed international projects have received an FID since it started tracking the many delayed projects in 2015 in the wake of the oil price plunge. The development cost of those projects is expected to be USD 78 billion.

The total spending for all projects will be larger because Rystad only looks at projects that had been put on hold, and does not include the ones sanctioned “more or less” on schedule after appraisal drilling was completed.

On the downside, the list of projects on hold in the energy information company’s UCube database keeps growing.

“The ongoing results of the oil price pain is clear to see—still over 100 projects delayed,” accounting for nearly 35 billion bbl of oil equivalent and USD 300 billion of potential spending, says Readul Islam, a research analyst for Rystad Energy.

Operators working in areas with high development costs, such as deep water and the Canadian oil sands, have reduced costs but need help from the price of oil to justify investing in growth.

“I feel the delayed projects list continues to grow because most people are seeking evidence of a sustained recovery in prices, which has so far remained stubbornly elusive as prices largely track sideways,” he said.

In part, these long-term efforts suffer in comparison to onshore projects that can pay back on their initial investments in a fraction of the time. In a world oversupplied with oil, decision makers are in no hurry to make big, long-term commitments.

For example, BP announced last December it would fund the Mad Dog 2 development after revamping the delayed project to reduce its cost by 60%. But the final decision only came recently when its partners BHP Billiton and Chevron officially joined in.

“All input assumptions need to be questioned and rechecked to ensure they lead to acceptable profits. This stretches project timelines,” Islam said. “Also stretching timelines is the possibility some investment boards are putting off a sanction decision, hoping to catch the bottom of the cost cycle.”

Compared with 2016, though, offshore projects are moving closer to being back in the money.

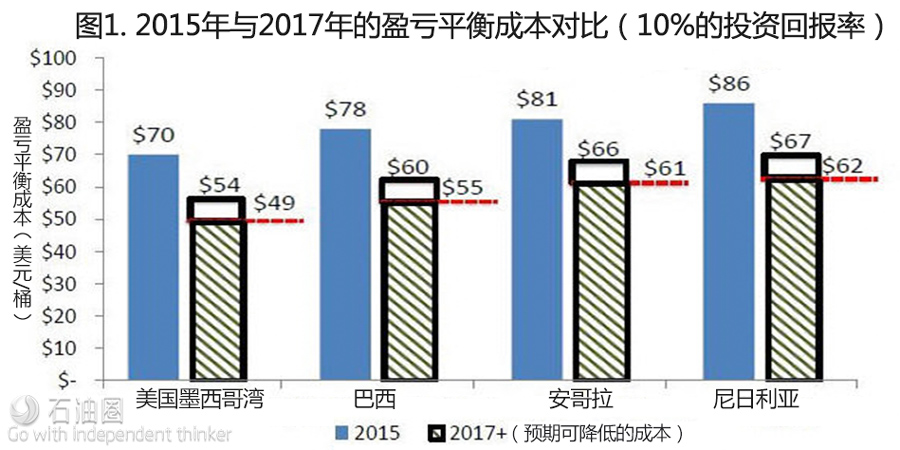

“The numbers are better but not amazing,” said Dan Pickering, chief investment officer for the firm of Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., pointing to a chart showing lower average break-even costs in key deepwater basins. As a result, he sees new field development offshore “emerging from the abyss” with capital expenditures rising sharply from last year’s dismal level.

The deep slump has battered the offshore service sector, and contributed to shrinking reserve totals for the biggest international oil companies.

A jump in project sanctions might help these publicly traded companies avoid a third straight year of declining reserves.

Proved reserves declined in 2015 and 2016 for 68 companies tracked by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), using data in earnings reports.

The big declines were reported by the larger producers in the group, and were concentrated in the Canadian oil sands, where billions of barrels of reserves had to be subtracted from the proven total because they will not be developed anytime soon.

Going forward on big field developments could change that. For example a final decision is expected later this year on the Libra field, which could significantly add to the reserve totals for Petrobras and its partners.

While an early estimate puts the ultimate production of the field at around 10 billion barrels, the amount added will be a judgment call based on the likely output from the initial development.Rebuilding reserves quickly will be tough at a time when spending on exploration and development is down.

“It is an industry that is doing its best to right-size its cost structure but there is not a lot of dollars to go around,” Pickering said.

In some companies, cash is so short that development is not an option. “The (delayed) list also continues to grow as smaller companies fighting to stay afloat in the current environment throw in the towel and either farm out their assets, or even enter bankruptcy,” Islam said.

In this market, companies are working with investment bankers to add reserves. Last year, the reserves purchased by the 68 companies tracked by the EIA were far higher than any other year covered by the chart dating back to 2011.

Longer term, Pickering said deepwater exploration is ideally suited to fill the gap for major oil companies. Remote, offshore fields offer big oil and gas potential finds in a place where those players have resources and skills that others do not.

But exploration results show the cost of failure remains high. Each year Tudor Pickering tracks 50 wells to watch, and the futility level tends to be consistent, with only about 15% of them really successful.

“Finding oil and gas is tough, and finding oil is tougher,” Pickering said.

The offshore market is poised for growth in the next 4 years, but unconventional production must maintain a steady pace if the industry is to meet the supply levels needed for consistent growth in the price of oil, an analyst said.

At a presentation, “Offshore—Rigged for Return,” hosted by the Houston chapter of the United States Association for Energy Economics (USAEE), Oddmund Fore examined Rystad Energy’s outlook on future offshore oil and gas operations. Fore, a senior analyst in the oilfield services division at Rystad, spoke about the state of the offshore drilling market.

Fore said that, in previous decades, the industry significant overcapacity of oil reserves triggered lengthy cycles of underinvestment on new projects and subsequent economic downturns. Strong oil demand and limited capacity resulted in price increases, high activity, and strong but costly reserves replacement. Fore said the current oil price downturn is similar in nature, with overcapacity and US shale growth triggering the collapse. As such, he said massive underinvestment in recent years should trigger a new growth cycle, with shale production likely to smooth any drastic fluctuations in price.

“We are pretty optimistic for the offshore sphere,” he said. “We have started to see some positive signals that we have already reached the bottom, and with new contracts coming in, we can start to reshape and turn around this industry.”

Though offshore production will help with growing demand, Fore said it would not be enough to meet the supply necessary to sustain oil price growth. He said the industry will need unconventionals to help fill the supply gap, approximately 1.3 million bbl/D of unconventional production each year. Fore referred to this as the “call on shale.”

“The industry needs [unconventionals] if it wants to turn around quickly and provide volumes for rising demand in the short term,” he said.

Reduced costs should also help foster growth in offshore production. Fore said the deepwater cost curve has decreased 15% in the past year, with North America, South America, and Western Europe being the regions with the highest pre-sanction spends. The lower oil price was not the sole reason for these reduced costs: While downsizing and simplification of project scopes played a part, Fore said improved project design—including an added focus on increasing standardization and reducing complexity—and reduced contingencies also led to the drop in deepwater spend, along with other efficiency gains and currency gains. The re-engineering and downsizing of projects, he said, will be important as the industry continues to improve the economic picture of the offshore sector.

Another thing playing a role in cost reduction is the increase in drilling speed. Fore said that a “silent revolution” has been taking place on this front in Norway, where the average meters drilled per active drilling day on exploration and production projects has increased from approximately 80 in 2011 to 176 in 2016. This improvement in drilling speed has also been observed elsewhere. Fore attributed an improvement in speed for presalt wells drilled by Petrobras and GALP in Brazil to a corresponding increase in the natural learning curve as these wells matured. He also pointed to similar improvements in the US Gulf of Mexico, as Chevron has been able to reduce its drilling times by 50% from 2012 to 2015.

“We need shale, but we also need offshore, especially with a deepwater,” Fore said. If you combine [deepwater and offshore shelf] as a whole, you see something that gets bigger and is a very relevant player. It’s important to the whole picture. It takes time to sanction a field, to develop a field, and to get the volumes coming out. It’s not happening overnight.”

Fore’s presentation took place at the Houston branch of the US Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

石油圈

石油圈