Guyana is not usually mentioned as one of the top targets for investment in Latin America. The country, which has a population of around 800,000 and a landmass roughly equivalent in size to Kansas, sits sandwiched between Suriname and Venezuela. A former British colony that is the only officially English-speaking country in South America, Guyana has never been particularly well integrated with its Spanish-speaking and lusophone neighbors. Most people in the country speak Guyanese creole rather than Spanish or Portuguese. Overall, Guyana’s GDP (which is worth just over $3 billion) is less than 1% of the economic output of regional heavyweights such as Colombia and Venezuela. In 2017, however, after a major off-shore discovery, Guyana’s oil industry is attracting new attention from foreign investors. Some analysts believe that Guyana could soon become one of the region’s top oil producers.

To get a sense of what’s happening in Guyana, I reached out to Daniel Gray, the Associate Director of The Caribbean Council, a London-based consultancy.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery: Guyana has been receiving some extra attention lately due to the discovery of offshore oil. How significant is the find?

Daniel Gray: The oil discoveries within the offshore Stabroek Block are vast, and exploratory drilling continues to push up the estimated total barrels of recoverable oil. In the wake of the initial May 2015 discovery, Minister of Natural Resources Raphael Trotman announced that there could be as much as 700 million recoverable barrels of high-quality oil, something which ExxonMobil, Stabroek’s primary operator, described as “a world class discovery.”

Since then, further successful exploratory drilling in Liza and the nearby Payara fields have led estimates of recoverable oil to double, to 1.4 billion barrels. Even based on more conservative estimates the market value of the oil produced would be in excess of $41 billion, based on current oil prices. To put this in context, the size of Guyana’s economy currently stands at around $3.4 billion.

For many, the find has quite literally put Guyana on the map. The 6.6 million acre Stabroek Block is shared between ExxonMobil, whose Guyanese affiliate holds a 45% interest, while Hess and CNOOC Nexen hold the remainder, at 30% and 25%, respectively. The finds have attracted many more Exploration & Production companies, including Tullow Oil, Eco Atlantic, Repsol and CGX Energy Inc. Some of these companies have operations in Guyana which predate the Liza find, and are prospecting neighboring blocks including Canje, Kanuku and Demerara with renewed vigor.

I think the recent finds in Guyana pale in comparison to the reserves in neighboring Venezuela, a country which holds the largest reserves of oil in the world, at almost 300 billion barrels in conventional oil. However, Guyana does not suffer from the same political risks as Venezuela, a country where resource nationalism since the turn of the millennium has led most foreign oil companies to leave. ExxonMobil, the company leading the development in Guyana, might understand the difference better than most. ExxonMobil actually won a $1.6 billion settlement in 2014 after its assets were expropriated in Venezuela in 2007.

Right now traditional oil industry heavyweights in the region such as Brazil and Colombia are offering improved terms to investors, but still struggling in the face of low oil prices. While there are a lot of unconventional plays opening up in countries such as Argentina, and the 2013 energy sector reforms in Mexico have lifted levels of investment across the Gulf, I think Guyana’s finds continue to stand out as the most significant oil and gas development in the region in recent years, and it certainly merits the extra attention it has been receiving.

Parish Flannery: What impact is this discovery having on Guyana’s economy, and what roadblocks are being addressed in advance of these reserves coming on stream?

Gray: The immediate impact on the economy has been a sensory one; business confidence locally is high and there is a newfound buzz around Georgetown, the country’s capital city. And there’s good reason for it; while it may be at least another three years before the Liza and Payara fields reach the production phase, the government is moving quickly to address a number of roadblocks, especially the country’s significant infrastructure deficit.

Leading the way in this regard is a $500 million investment announced in December 2016 to build an onshore oil and gas service hub on a greenfield site at the mouth of the Berbice River, north of New Amsterdam. Yet there is a lot more to do- from building hotels to accommodate foreign oil and gas workers, to improving roads, port terminals and telecommunications networks. There will be no shortage of opportunities for investors, consultants and engineering firms from a range of sectors. The developments also stand to be transformative for the wider Guyanese economy, which will benefit from the logistical and infrastructural improvements many of which are long overdue. Key projects include the upgrade of the road to Brazil through Lethem, the replacement of the bridge over the River Demerara and the bridge to Suriname in the East.

Guyana’s government is also modernizing its legal and regulatory environment, with the intention of ensuring that the country’s incoming oil wealth is managed effectively. Importantly for investors, the government appears keen to convey that investors have a stable and clear policy environment in which to operate. Having engaged international organizations on these issues, the government is setting up the institutions and legal framework needed to establish best practices in managing the industry and the revenues. This includes a regulatory Petroleum Commission, competitive local content requirements, and the establishment of robust health and safety and environmental standards.

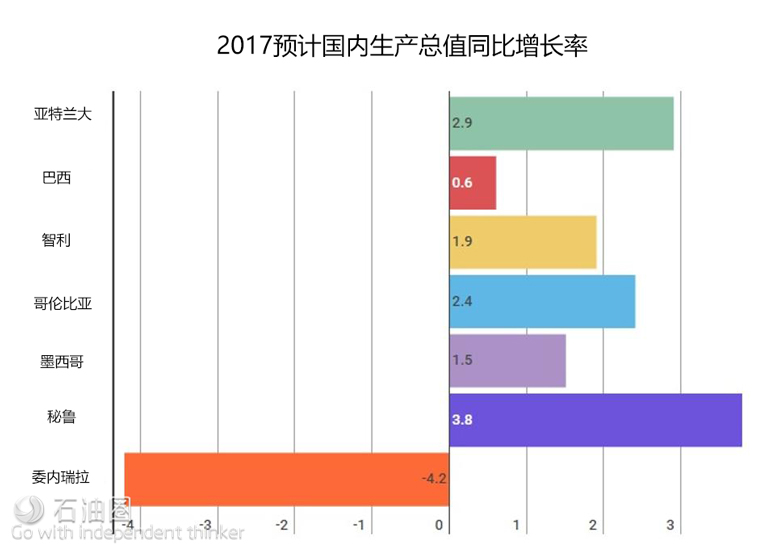

Crucially, the government has also created a Sovereign Wealth Fund intended to manage revenues equitably, and ensure that the benefits accrued are used to develop the country effectively. This month, the government also proposed accompanying Integrity Commission Laws intended to mitigate the governance and corruption risks associated with a sudden influx of resource wealth. Like many countries, Guyana’s political parties are split along ethnic lines with the potential for real divisions; it is vital that all of the different groups in Guyana feel confident that the newly found oil and gas wealth is benefiting their communities to shared effect. In the short term Guyana’s economy is expected to grow at just over 3% in 2017, faster than most of the region’s major economies.

Parish Flannery: What longer-term challenges will Guyana still need to confront?

Gray: One key long-term challenge will be high-quality job creation. Infrastructure construction will provide opportunities in the near to medium term, with the oil and gas services hub already set to create 600 local jobs. However, as was recently recognized by Prime Minister Nagamootoo at a conference convened by the Guyana Oil and Gas Association [GOGA], the oil industry will not provide locals with quality long term employment. This is because oil can be largely processed and exported using minimal onshore infrastructure, unlike natural gas which tends to require a lot more onshore management, as seen over the past several decades in nearby Trinidad & Tobago. Moreover, there are currently no plans to build local refineries.

Therefore, despite local content regulations requiring the training and employment of Guyanese nationals, there will, in reality, be relatively few high quality jobs available. As a result, Prime Minister Nagamootoo stated that the government will need to look to develop a more integrated economy, where locals can find quality jobs in a range of ancillary support sectors to the oil industry, as well as traditional sectors such as sugar, agriculture and mining.

This, however, raises an additional longer-term challenge posed by the expected influx of oil revenues; Dutch disease. Guyana’s meagre energy demands means that it is going to be exporting the vast majority of its oil. With a sudden increase in transactions taking place using Guyanese Dollars, its exchange rate is likely to appreciate significantly. The creation of a sovereign wealth fund will allow the Guyanese Government to guard against some of these risks but nevertheless it will be highly challenging to retain cost-competitiveness for traditional exports from Guyana such as rice and sugar.

Guyana will need to rapidly assess how it will protect its key industries going forward so that it remains a diversified economy not overdependent on oil and gas in the way that Trinidad has become. Part of the answer must be to take this opportunity to make the long-term capital investment industries such as sugar and rice need to mechanize and move up the value chain.

Finally, it’s important to consider wider developments in global energy. The continued glut of global oil supplies from conventional and unconventional sources, combined with increasingly competitive renewable energy and carbon taxes may altogether conspire to keep the global oil price low. Nonetheless, for Guyana, at whatever the oil price, the opportunity remains huge and represents a once in a century opportunity to transform the lives of its people.

石油圈

石油圈