这家世界上最赚钱的石油公司正在悄然发生着变化……

来自 | 经济学人

编译 | 宁采臣 杜威

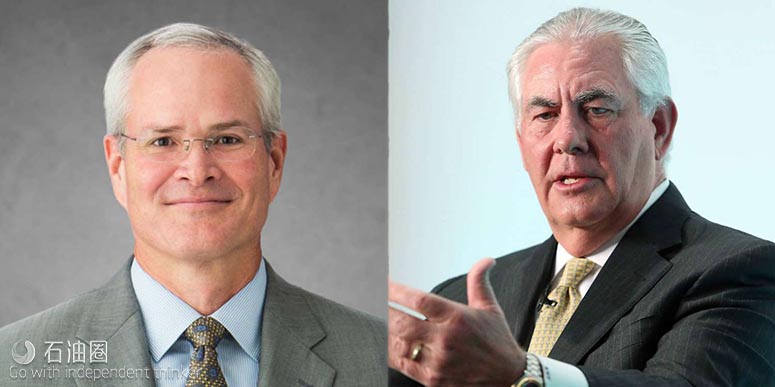

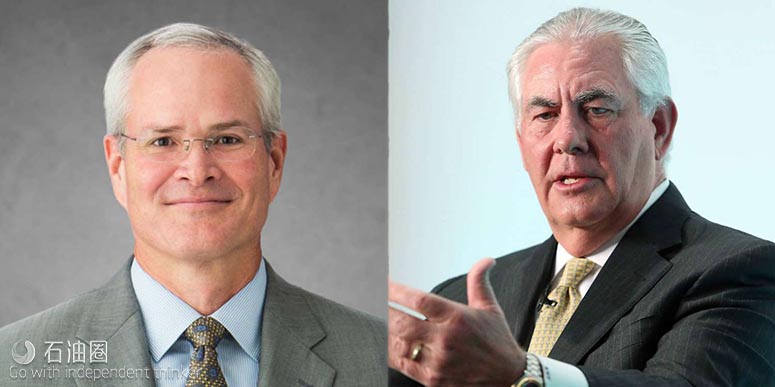

前任CEO蒂勒森按规定于今年初正式退休,但特朗普的点名指派却将蒂勒森推至风口浪尖,他掌管的埃克森美孚没能逃过舆论的漩涡,新CEO Woods一时间也成为热点人物。

下游专家出任新CEO

路透社消息称,蒂勒森离开后,埃克森美孚董事将剩余12人。事实上,蒂勒森和埃克森美孚均希望加速这一流程,前者相信越快卸任CEO才能越快进入国务卿这一角色,而埃克森美孚则希望尽快任命新掌门,才能尽可能地降低对业务发展的影响。于是,Woods提前进入了我们的视野。

维基百科上,对Darren Woods的介绍只有寥寥几行字,主要的内容是他的生辰年月,而埃克森美孚公司官方对他的介绍更为简短:今年52岁。据了解,Woods与蒂勒森一样,都毕业于德克萨斯大学,并于1992年进入埃克森美孚公司,曾就职于埃克森美孚炼油与供应公司、埃克森美孚化学公司和埃克森美孚国际公司。

不过,Woods一直工作于下游领域,对炼化、运输、化学品等业务非常熟悉,还曾担任过埃克森美孚精炼和运输部门负责人,此前从未接触过上游勘探和生产领域。但埃克森美孚作为全球最大上市油企,勘探和生产领域才是“重头戏”,“下游专家”Woods能否带领其走出增长滞缓的困局,业内为他捏了一把冷汗。

现在的埃克森美孚被称为“瘸腿巨人”

今年1月31日的公司报表显示,埃克森美孚的利润继续下降。从2014年开始,公司股票就一直在下跌,现在一年的利润比不上过去一个季度的利润,甚至比1999年兼并Mobil之前还要低。

由于这两年油价大幅下降,埃克森美孚和其他大的石油公司一样,公司利润率大幅下降,甚至需要借钱去维持股票分红和继续勘探开发的投资需求。去年4月,标准普尔剥夺了其AAA评级,降至AA+,这是自上世纪30年代美国大萧条以来,埃克森美孚首次失去AAA评级。

在商业环境如此恶劣的时候,埃克森美孚在美国天然气的项目又减记20亿美元。预计在接下来的几个星期,公司的原油储量会从250亿桶下降到204亿桶,因为原油的购买成本太高,增加这46亿桶则无法盈利。

该公司股价表现目前比雪佛龙低20%,并且同样低于于欧洲的同行们,包括壳牌,道达尔,英国石油。埃克森美孚的业务规模和工程技艺,无疑是登顶石油行业的最大助力,然油价萎靡至今,行业发展动力不足,该公司在这场低迷周期中日渐憔悴。

为了弥补上述问题,埃克森美孚试图将Permian Basin的油气产量翻倍。为使产量从每天14万桶增加到每天35万桶,公司今年做出的第一个交易就是用66亿美元现金加股票的方式购买Woods区块。相对于俄罗斯北极圈高成本的勘探项目,埃克森美孚要购买更多低成本的页岩气区块来丰富自己的资产组合。

而对比雪佛龙,埃克森美孚似乎又略逊一筹。雪佛龙从20世纪20年代就占有Permian的一些区块,拥有超过200万英亩的土地,而埃克森美孚最近只购买了25万英亩。Permian区块的页岩油收益很不错,然而埃克森美孚通过收购了XTO能源,将赌注押在了页岩气上面。由于气价低于油价,埃克森美孚难以获得理想中的高额回报。

Woods的机遇和挑战

Woods掌管埃克森美孚之后,需要直面埃克森美孚的长期发展问题。

特朗普对化石燃料的青睐有加,让石油业再次燃起了希望,而有了蒂勒森的“庇护”,埃克森美孚的业务前景预估更是不知好了多少倍。美国政治新闻网站《政客》撰文称,即将出任国务卿的蒂勒森,势必会回报“老东家”,特朗普对化石燃料的大举推动被认为是埃克森美孚重振旗鼓的最佳机遇。

而且,Persian海湾是埃克森美孚未来的机遇所在,这里勘探开采原油的成本比较低廉,只不过存在长期的地缘政治风险和比较激励的商业竞争。

机遇伴随着挑战,也伴随着危机。

Woods接手公司后面临的一个挑战是气候问题。化石能源的发展前景需要进一步讨论,环保主义者和一些投资人要求公开公司具体项目发展情况的透明度。2月21日,公司任命了曾经在联合国任职的气象学家Susan Avery进入董事会。一些舆论认为这不过是一种做秀,但是这种进步的举动确实会悄然改变公司在对应气候变化方面问题的思考方式。

公司还面临一个潜在的危机,即公司的前任老板和现任总统亲密的工作关系。这可能导致公司不能继续坚持自身优秀的传统。近期,埃克森美孚的高层与共和党的国会议员共同提出废除一项条款,旨在减少公司在富裕国家的腐败问题并且督促公司对国外政府公布所有的付款明细。

也许Woods还沉浸在当选的喜悦中,但他面临的局面并不乐观。能否扭转蒂勒森留下的“烂摊子”局面,我们还未可知,但是可以知晓的是,埃克森美孚不同以往地提拔了下游专家为公司最高决策人,从侧面说明,该公司开始越来越重视炼化行业。

WITH an institutional culture that lies somewhere between the marines and the boy scouts, ExxonMobil tends to avoid personality cults. Even so, it is surprising how little is known about Darren Woods, the chief executive who last month succeeded Rex Tillerson, America’s new secretary of state. Mr Woods’s Wikipedia biography is a few lines long. Rather than reveal the year of his birth, ExxonMobil just says he is 52. Never mind: the most significant fact about him is that he comes from the refining and chemicals side of the business, which hums along so efficiently that ExxonMobil is widely considered the world’s best “integrated” oil company. Yet it is upstream—the exploration and production part—where his hardest tasks lie.

On January 31st the company reported another year of plunging profits, which have buffeted its share price since 2014 (see chart). It earned less in a year than it used to earn in a quarter, and also less than Exxon made before its $80bn merger with Mobil in 1999. Profits among its “Big Oil” peers have likewise been clobbered by falling oil prices over the past two and a half years. It is also not alone in having to borrow heavily to meet its dividend and investment obligations; last year it lost its coveted AAA credit rating.

Even so, it was a surprise that it took a $2bn hit on the value of some natural-gas assets in America; in the past it has avoided such write-downs. In coming weeks, it is expected to remove up to 4.6bn barrels of North American crude from its 25bn barrels of proved reserves, because they are too costly to produce profitably. That will be yet another rare occurrence.

It will add to a sense that ExxonMobil is struggling to find low-cost sources of oil production to prepare it for a world of potential oversupply. That impression has led its shares to lag behind those of Chevron, its biggest American rival, by 20% in the past year, as well as those of European peers, Royal Dutch Shell, BP and Total. Lysle Brinker, head of oil-company research at IHS Energy, a consultancy, says that, although historically ExxonMobil’s shares have traded at a higher premium to the value of its assets than its big rivals, in the past year “Chevron has overtaken it”.

In an effort to redress the problem, the company’s first deal in the Woods era has been a $6.6bn stock-and-cash purchase aimed at more than doubling its output in the Permian basin in Texas and New Mexico, to 350,000 barrels a day from 140,000. ExxonMobil hopes that acquiring more shale deposits will boost the proportion of oil and gas in its portfolio that is relatively quick and inexpensive to produce, compared with more costly and complex projects in places like the Russian Arctic. A potential boon is a bumper discovery in the oceans off Guyana, in South America.

Chevron has been far luckier. It clung onto legacy oilfields in the Permian that go back to the 1920s, and has 2m acres there, compared with the 250,000 recently bought by ExxonMobil. It has fared better from shale oil, whereas ExxonMobil bet big on shale gas via a $31bn merger in 2010 with XTO Energy. Since then gas assets have become even less valuable than oil ones, leaving ExxonMobil struggling to make amends.

An alternative for Mr Woods would be to do deals in the Persian Gulf, where oil is also cheap to produce but where there are rising competitive and geopolitical pressures. Mr Brinker notes that state-owned oil companies are nowadays offering less lucrative joint ventures to Western firms. A looming privatisation is likely to make Saudi Aramco, the only oil company that is bigger than ExxonMobil, into an even stronger competitor.

Adding to the challenges, Mr Woods takes over the company at a time when climate change is raising questions about future demand for fossil fuels. Environmental activists and increasing numbers of investors are demanding more transparency. On February 1st the firm appointed Susan Avery, an atmospheric scientist who formerly advised the UN, to its board. Some dismissed this as a publicity stunt. But it could be a bold move to shape its thinking on climate change.

One danger is that with its former boss standing shoulder to shoulder with Donald Trump, the firm reverts to its habit of insisting that it knows best. Many will be disheartened that, under pressure from companies including ExxonMobil, Republicans in Congress were this week planning to scrap a rule, aimed at reducing corruption in oil-rich countries, that forces firms to publish all payments to foreign governments. There is no reason to doubt ExxonMobil’s adherence to what it terms its “culture of integrity”. But it is increasingly important for oil firms not just to behave like good global citizens, but to be seen to do so, too.

未经允许,不得转载本站任何文章:

-

- Linda

-

石油圈认证作者

- 毕业于南开大学传播学专业,以国际权威网站发布的新闻作为原始材料,长期聚焦国内外油气行业最新最有价值的行业动态,让您紧跟油气行业商业发展的步伐!

石油圈

石油圈