Deepwater Sector In Deep Trouble

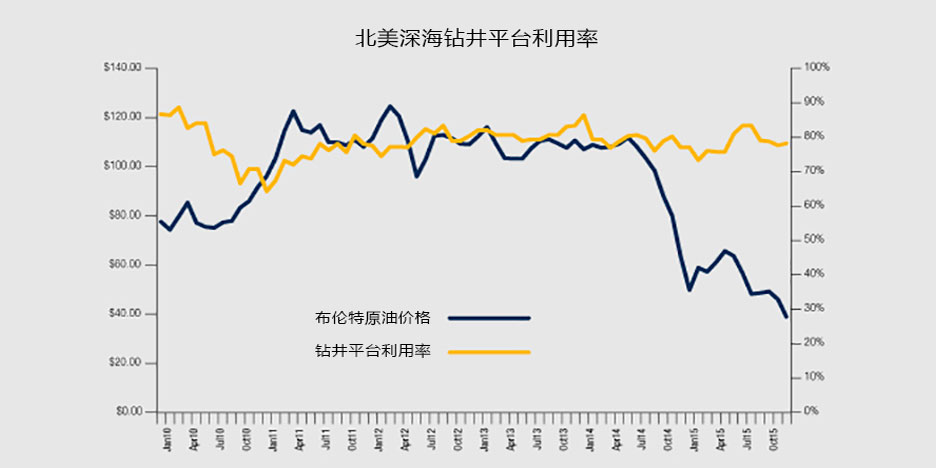

Drilling activity in the deepest parts of the world’s waters can yield tremendous oil volumes, but exploring thousands of feet below sea level is also the most expensive of energy’s high tech endeavors. And in an environment of $30 oil, investment in deepwater production is pouring out.

Beyond a rebound in oil prices, recovery of the deepwater sector could take an additional two years,SajjadAlam, senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service told Rigzone.

And some companies are opting to not even try to make deepwater work. In an Oct. 29 earnings call with analysts, ConocoPhillips Executive Vice President for Exploration and Production Matt Fox said one of the company’s largest assets includes 2.2 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico, which includes three existing discoveries. But the super major made it clear the company won’t be drilling there.

“This is a strategic decision to leave – to exit deepwater exploration,” he said.

ConocoPhillips isn’t the only deepwater investor reconsidering its options. In a January 2016 report, Wood Mackenzie (Wood Mac) noted that 22 major projects worth 7 billion barrels of oil equivalent (Bboe) in commercial reserves have been delayed during the last six months. That’s in addition to the deferral of 46 developments and 20 Bboe in reserves the research firm identified last June. All told, that’s 68 major projects to develop and 27 Bboe put on hold.

“The impact on future production is significant,” Wood Mac wrote. “And with oil prices dipping to new lows at the start of 2016 and capital allocation tightening, the list will continue to grow.”

Of those projects,deepwater accounts for more than half of the new project deferrals. The sector’s high project breakeven rates, enormous capital requirements and relative inflexibility combined to make it unpalatable.

All of which will lead to a necessary dip in supply, said James West, senior managing director at Evercore ISI.

“This cancellation of projects is going to leave us a gap in future production, which we will eventually need,” he told Rigzone. “We may find ourselves in a really tight spot in a few years from now as this excess oil supply gets soaked up and we’re needing incremental supply … As we cancel more of these projects, it can actually help the oil market out because it does take the future supply off the market,[which] should be able to sniff out that we’re going to get tighter, faster.”

Taking Debt, Losing Credit

But as Alam noted, things will get worse for offshore drillers before they improve.

“The worst is yet to come from a credit perspective, in terms of where drillers are today versus where they will most likely end up over time. The reason being [that] in the offshore drilling space, deterioration happens gradually because of the contractual protection that benefits drillers,” he said. “As these contracts expire, they will be looking at much lower day rates, and many of their rigs may not even be re-contracted.”

As a result, the revenue stream dries up, margins continue to compress, and rig companies find themselves in a world in which they had a capital structure built for certain day rates [and] certain asset values, he said.

“Now, asset valuation has come down dramatically. Day rates have come down dramatically. So their debt level is going to look very high, relative to their cash flows,” Alam explained.

Consequently, Moody’s lowered ratings gradually to account for increasing credit risk. After downgrading most offshore drillers in October 2014, the investors’ service intends to again review offshore drillers for further downgrade.

A Deluge of Bankruptcies

Across the energy sector, more than 40 companies filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection last year. Alam noted that the early December bankruptcy of international offshore drilling contractor Vantage Drilling Co.’s bankruptcy is evidence of what happens when a company is overburdened by their own debt.

In Vantage’s case, the company had three drillships and four jackups, each built within the last five years at an average cost of around $650 million per drillship and $225 million per jackup,Alam said. In today’s market, those drillships are probably worth between $300 million and $350 million, about half as much as they cost to build. Jackups likely haven’t fared as poorly, but still, they’re probably worth less than $150 million each. In addition, Vantage had a significant amount of debt,Alam said.

“So what’s going to happen is essentially the debt holders are going to become equity holders after taking a significant loss. A lot of these over-levered companies will probably file for bankruptcy and if that debt goes away, maybe there will be an interested buyer for the rigs,” he said. “But at their current level of debt, there is not a lot of interest.”

Consolidation in a down market is a natural progression,Alam said, last seen in earnest in the 2010 down cycle.

“Most rig companies feel the earnings prospects look weak, and it’s not going to improve in the near future. Unless there is a deep, deep discount, [another company] is not going to volunteer to acquire that rig. Everybody is holding back for prices to come down even more. A lot of these rig companies – they have attractive assets, but they also have a lot of debt … because equipment is so expensive,” he explained.

A couple of weeks after Vantage filed for bankruptcy, it was Norway’s Dolphin Group ASA, an offshore seismic survey company for the oil and gas industry, heading to the bankruptcy courts.

There’s no question that offshore drilling is tough, and while some producers have managed to shore up their balance sheets, it’s a mixed bag for service providers, West said.

“It’s a question mark in our minds for the supply vessel companies, maybe not so much for the U.S. based ones, but some of the Norwegian companies and some of the Asian companies, are likely to go out of business,” he said.

The global market is oversupplied by about a million barrels per day, but that could turn around by the end of the year if U.S. shale production cuts down, West said. Already, supply appears to be dwindling in 2016, he said, hinting at a balance between ever-important supply and demand and giving a bounce to oil prices. That will put rigs onshore back online, but deepwater will likely be the last of the rig population to return to work.

“We could look at a recovery for deep demand materializing in late ‘17, or early ‘18 but I don’t see it before that,” West said.

石油圈

石油圈