许多专家认为,被称为“蓝金”的天然气将是不可替代的过渡能源。现在及将来,关于“蓝金”天然气主要运输线路的地缘政治和基础设施问题有哪些?管网建设存在何种挑战?本文将介绍近年来全球范围内十大最重要的天然气管道项目。

来自 | AGE

编译 | 白小明

后石油时代,天然气是大势所趋。俄罗斯“北溪”天然气管道(Nord Stream)扩建项目、意大利和阿尔及利亚的GALSI输气项目、地中海丰富资源储量的开发、南部天然气走廊(SGC)的相关利益及猜想、土耳其天然气管道及向东北的通道面临的挑战……这些项目的发展历程和轨迹你都知道吗,本文将为你一一解读,同时聚焦于全球天然气管网的最新动态。

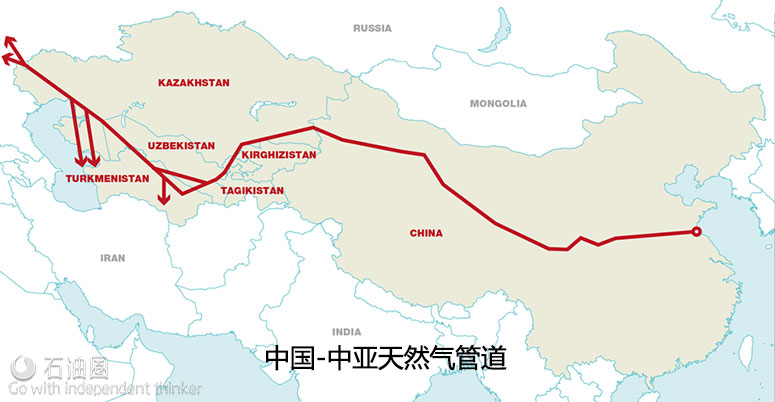

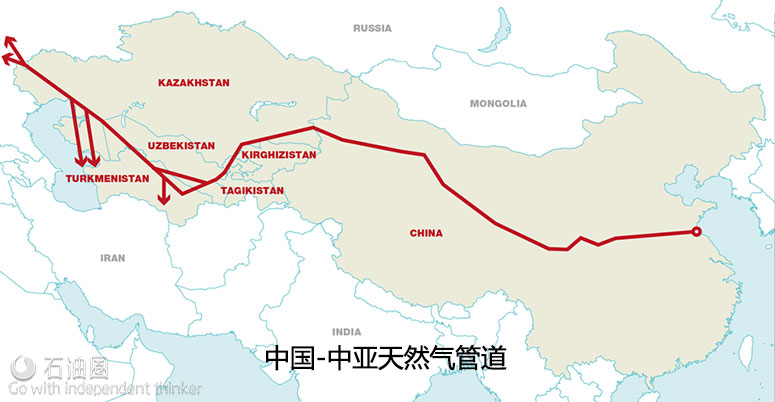

六、中国-中亚天然气管道

中国-中亚天然气管道是从土库曼斯坦向中国新疆(通过乌兹别克斯坦和哈萨克斯坦)输送天然气的主要基础设施,由中石油(CNPC)和中亚国家的合作公司共同管理,年输气能力约为550亿方,相当于中国能源需求的约20%。该综合设施计划在相距1830公里的中国新疆的霍尔果斯和土耳其城市Gedaim(与乌兹别克斯坦接壤)之间铺设三条平行的天然气管道。三条管道的总长度约为3600公里,两条输气管道中的第一条A线,于2008年7月启动,于2009年12月投入运行;B线紧随其后于2010年10月投入运行。双管道系统在2011年的输送能力为300亿方/年;第三条管道C线于2012年9月开工,于2013年底竣工,该管道于2014年正式投入运行,使天然气管道输送能力每年增加250亿方。

2013年9月,中国与乌兹别克斯坦、塔吉克斯坦和吉尔吉斯斯坦签署了政府间协议,建设天然气管道D线,该管道于2014年9月13日开工,目前仍在进行中。新的天然气管道将把土库曼斯坦Galkynysh超大型天然气盆地与中国相连,并将使中亚-中国天然气管道综合设施的总输送能力每年增加300亿方,达到850亿方,从而成为中亚最大的天然气输送系统。

七、土耳其天然气管道

土耳其天然气管道,旨在通过黑海将俄罗斯的天然气输送到欧洲,该项目是在2014年12月,俄罗斯总统普京访问土耳其期间首次提出的。该项目是在Shah Deniz财团选择采用南部天然气走廊(SGC)将天然气输往欧洲之后确立的,该财团控制着位于里海沿岸阿塞拜疆的油田。根据俄罗斯的说法,土耳其天然气管道项目将不得不解决“南溪”天然气管道的建设问题,后者为一大型天然气管道项目,旨在通过黑海水域、保加利亚、塞尔维亚和阿尔巴尼亚将俄罗斯南部天然气输往意大利。

然而,该项目于2015年11月陷入僵局,原因是土耳其空军在叙利亚边界上空击落了一架俄罗斯战斗机。这一突发事件恶化了两国的关系,甚至足以引起两国之间的军事冲突。2016年7月土耳其政变失败后,两国关系明显改善,在圣彼得堡普京和土耳其总统埃尔多安举行的会议上,两国达成和解,并重启了该项目。土耳其天然气管道项目预计将基于BOT(兴建、运营、转移)的融资模式,并包括两条线路:第一条满足土耳其国内市场,输气能力为约157.5亿方/年,第二条输送等量的俄罗斯天然气到欧洲。

八、跨里海天然气管道项目——里海困境

跨里海天然气管道项目,旨在连接土库曼斯坦的Türkmenbaşy和阿塞拜疆的巴库,作为南部天然气走廊的自然延伸。土库曼斯坦、哈萨克斯坦和欧盟强烈支持该管道的建设,欧盟在2011年试图展开谈判,但谈判最终以仅剩两个前苏联国家而告终。然而,该项目却受到俄罗斯和伊朗的强烈反对,因为目前土库曼斯坦和哈萨克斯坦天然气主要通过俄罗斯和伊朗输往欧洲,如果管道走里海,将绕开俄伊两国。

俄罗斯和伊朗正在以环保名义反对铺设水下管道,并声称里海不是海,而是湖泊,因此,必须得到里海沿岸各国的一致批准才能进行资源的开发。此外,对于这一点,伊朗翻出了1921年和1940年与苏联签署的条约,其中管道建设涉及的所有其他国家均为谈判的参与国。这些条约仍然有效,而事实上建设管道也确实需要周边国家的一致同意。

如果里海被宣布为海,则尽管其四周封闭,根据1982年“蒙特哥湾条约”:沿岸各国控制12海里的水域,12海里之外,各国还可以开发利用离基线200海里的专属经济区。然而,如果里海被认为是一个湖泊,沿海国家只能在12海里内行使其专属管辖权,12海里之外,如果要开发利用海底区域,如开采资源或铺设管道,将需要一个国际权威机构协调资源的开采和分配。2016年1月,伊朗经济制裁解除后,使其成为了区域地缘政治格局的中心。目前,将伊朗天然气输往西部的主要基础设施采用Tabriz-Ankara天然气管道,尽管其设计输气能力为16亿方/年,但实际每年出口约10亿方天然气。

自2009年以来,伊朗已经开启了多个上游天然气项目,随着制裁解除,波斯湾地区的South Pars气田开发已进入第21阶段。该国在里海最深处也有巨大的天然气储量,但目前缺乏开采这些天然气的技术。伊朗现在有能力重新出台出口政策,但油价的下跌使其开始寻求更有利可图的亚洲市场。最近几个月,伊朗官员一再强调,由于长距离(1800公里)及运输费用的原因,铺设经土耳其将South Pars天然气输往欧洲的天然气管道不具可行性。因此,伊朗政府已将发展天然气液化基础设施作为优先考虑。

同时,伊朗和俄罗斯正在推动兴建南部天然气走廊项目,连接俄罗斯、阿塞拜疆和伊朗,这为亚洲和欧洲的共同能源政策带来了新的期待。在过去两年里,伊朗总统鲁哈尼和阿塞拜疆总统阿里耶夫举行了七次会晤,而且在阿塞拜疆有约450家伊朗公司。伊朗与阿塞拜疆的关系,正和伊朗与俄罗斯的关系一样,不断巩固加强:俄罗斯正在推动一个框架协议,使阿塞拜疆和伊朗加入欧亚经济联盟。

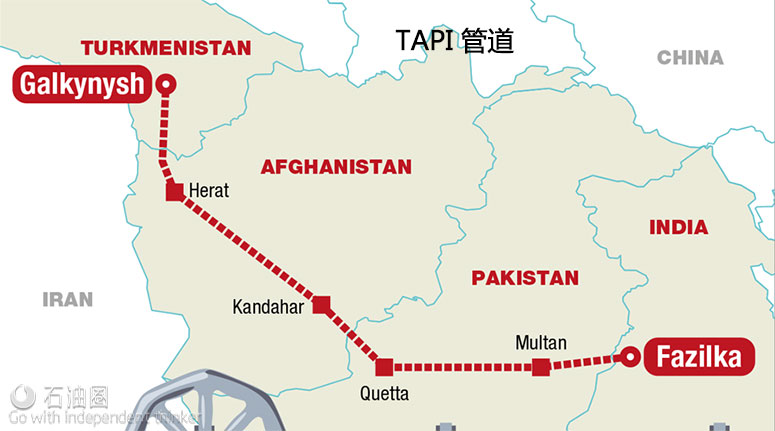

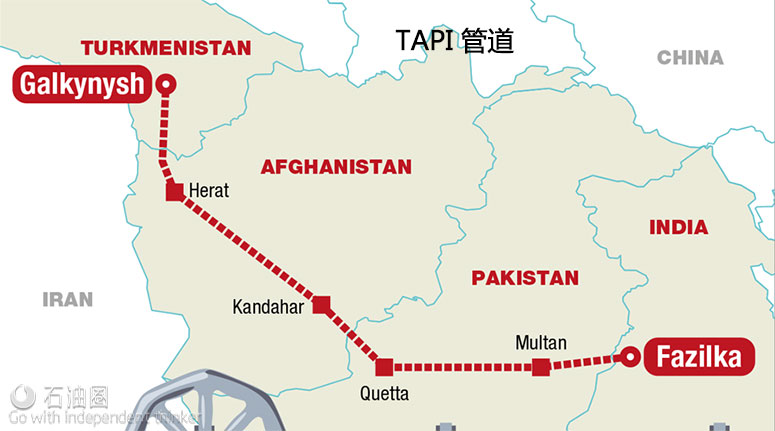

九、TAPI管道

自20世纪90年代以来,大家就一直在讨论从土库曼斯坦,经阿富汗,到巴基斯坦的天然气管道。当时,在美国总统克林顿的主持下,成立了中亚天然气管道联盟(Central Asia Gas Pipeline),由美国优尼科公司(Unocal)和沙特阿拉伯三角洲石油公司(Delta Oil)牵头。该项目计划将天然气从中亚输往印度洋,从而作为目前由俄罗斯控制的向欧洲出口天然气的替代路线。这样,俄罗斯将失去对中亚各共和国的战略控制。

但有一个问题:尽管苏联部队已撤出,但阿富汗内战仍在持续。阿富汗的团结统一,目前主要依靠古兰经的学生“塔利班”、沙特的资金以及巴基斯坦的军事支持和情报。实际上,“塔利班”实现了对大多数阿富汗地区的控制,但这与美国政府的想法并不一致。“塔利班”与基地组织结成了联盟,而后者的领导人本•拉登于2001年9月11日对美国发动了空袭,炸毁了世界贸易中心的双子塔,导弹击中了五角大楼。

2010年,当事四国政府签署了谅解备忘录,建设TAPI(土库曼斯坦-阿富汗-巴基斯坦-印度)天然气管道。然而,迄今为止只签署了初步协议,2亿美元已用于可行性研究报告。这条1800公里长的管道,预计从位于阿富汗边界以西200公里的土库曼斯坦Galkynish气田开始;然后穿越阿富汗的赫拉特、坎大哈和赫尔曼德三省,阿富汗境内长度为773公里;再穿过巴基斯坦的木尔坦和奎达省,巴基斯坦境内长度为872公里;最终到达位于印度北部旁遮普省的Fazilka市。

最终管道的成本预计约为100亿美元,预计输送能力约为9000万方/天,组成如下:3800万方到印度,3800万方到巴基斯坦,1400万方到阿富汗,然而,最近阿富汗已将其需求量减少到了400万方。该项目主要的问题是安全性。阿富汗仍然经历着无休止的武装冲突,赫尔曼德省由伊斯兰极端分子控制,甚至包括巴基斯坦西部省份,即所谓的部落地区,都不在巴基斯坦政府的控制范围。

十、北极圈——新的前沿阵地

极地冰川的逐渐融化,让石油巨头们纷纷开始对全球自然环境最恶劣的北极地区产生兴趣。从20世纪70年代第一次卫星调查以来,北极冰川体积已经减少了一半,这种趋势还在继续。2007年,欧洲航天局(ESA)宣布“西北航道(Northwest Passage)”是可行的,该线路经加拿大北极群岛,连通大西洋和太平洋,并穿越一直冰封的北冰洋。

然而,更为复杂的是“东北航道(Northeast Passage)”是从北海开始,经北冰洋,沿西伯利亚沿岸,穿过白令海峡和白令海,最终到达亚洲东部的太平洋沿岸。直到最近,由于浮冰和冰川的存在,该路线仍被认为是极其危险的,并没有纳入到中国与欧洲之间的正常贸易线路。

然而,冰川的融化,即使是普通的商船在7-11月可以通航,这对从中国到欧洲运输货物的公司极其有利。据气候学家称,按照目前的全球变暖的速度,在2030-2050年间,“东北航道”将全年安全通航。不久的将来,与北极地区接壤的国家可能将伸张自己的海洋权利,并开始行动起来维护自己的利益。

20年后,北极航线可能成为世界主要航线,进一步缩短航行时间,并避免走一些危险的通道,如仍然受到海盗侵扰的马六甲海峡;政治不稳定或有争议的地区,如中国南海;受货物重量限制的航道,如苏伊士和巴拿马运河。还有一个因素使北极成为全球最重要的地缘政治地区之一,即巨大的资源储量。

根据10年前的预计,全球30%的常规天然气储量和13%的石油储存在北极,并且北极还有大量矿物资源,如铀、金和钨。因为北极地区还从未进行过系统的勘探,也没有进行过精确的分析,所以预计的数量肯定还将增加。对北极地区最感兴趣的国家是俄罗斯,其从北极圈附近的资源中获得了占其GDP约15%的收入。2016年6月15日,俄罗斯石油公司(Rosneft)首席执行官Igor Sechin表示,西西伯利亚沿岸最大的油田位于Kara海,其潜在资源量与沙特阿拉伯相当,仅从这一点就可以看出北极地区巨大的潜在资源量。

Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline

The Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline is the main infrastructure complex for transporting gas from Turkmenistan to the Chinese region of Xinjiang (via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan). It is managed by the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), together with partner companies of the Central Asian countries. It has a capacity of approximately 55 billion cubic meters of gas per year, equal to approximately 20 percent of China’s energy need. The complex envisages the parallel passage of three gas pipelines covering a distance of 1,830 kilometers between the Turkmen cities of Gedaim (on the border with Uzbekistan) and Hogor, in the Chinese province of Xinjiang. The total length of the three pipelines is approximately 3,600 kilometers. The first of the two gas pipelines, line A, was started in July 2008, became operational in December 2009. Line B followed in October of 2010. The two-pipeline system had a capacity of 30 billion cubic meters per year during 2011. Work on a third pipeline, known as line C, started in September of 2012 and was completed at the end of 2013. The pipeline officially entered into operation in 2014, increasing the gas pipeline’s capacity by 25 billion cubic meters per year. In September of 2013, China signed intergovernmental agreements with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kirghizstan for the construction of line D of the gas pipeline, whose construction started on September 13, 2014 and is still in progress. The new gas pipeline will connect the supergiant gas basin of Galkynysh in Turkmenistan to China and will increase the total capacity of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline complex by an additional 30 billion cubic meters per year, reaching a total of 85 billion cubic meters, becoming the largest gas transport system in Central Asia.

Turkish Stream

The Turkish Stream gas pipeline, which is expected to transport Russian gas to Europe via the Black Sea, was first announced in December 2014, during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s historic visit to Ankara. The project was founded after the Shah Deniz consortium, which controls the Azerbaijani field off the Caspian coast, had chosen the Southern Gas Corridor to transport natural gas to Europe. According to Moscow, Turkish Stream would have then had to address the failed construction of South Stream, the large gas pipeline designed to transport gas from southern Russia to Italy via the waters of the Black Sea, Bulgaria, Serbia and Albania. However, the project was frozen in November 2015, after the Turkish air force shot down a Russian fighter jet on the border with Syria. This episode abruptly worsened relations between Moscow and Ankara, enough to fear that conflict might develop between the two countries. After the failed coup in Turkey in July 2016, relations between the two countries significantly improved and led to a reconciliation, one sanctioned by a meeting in St. Petersburg between Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and they have therefore relaunched the project. Turkish Stream is expected to be based on a BOT (Build, operate, transfer) funding model and should involve two lines: the first should supply the domestic Turkish market with approximately 15.75 billion cubic meters of gas per year, and the second should transport the same amount of Russian gas to Europe.

The Caspian dilemma

The Trans-Caspian gas pipeline project is designed to connect Türkmenbaşy, in Turkmenistan, to Baku in Azerbaijan. Regarded as a natural extension of the Southern Corridor, the pipeline is strongly desired by Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and the European Union, which, in 2011, attempted to launch negotiations to that end with the two former Soviet republics. The project, however, is strongly opposed by Russia and Iran, countries through which Turkmen and Kazakh gas is currently transported to Europe, and which would be bypassed if natural gas were to flow via the Caspian Sea instead. Moscow and Tehran are advancing environmental objections to the laying of underwater pipelines, and also claim that the Caspian is not a sea but a lake, and that, therefore, the exploitation of resources must be unanimously approved by all Caspian bordering countries. In this regard, moreover, Iran is recalling the treaties signed in 1921 and 1940 with the Soviet Union, of which all other countries involved in the negotiations were part. These treaties are still in force and in fact require the unanimity of the bordering states.

If the Caspian is declared a sea, albeit closed, it would be subject to the 1982 Treaty of Montego Bay: the bordering states govern within 12 nautical miles, but beyond these 12 miles they can exploit an exclusive economic zone that can extend for up to 200 miles from the base line. However, if the Caspian is acknowledged as a lake, the coastal states could exercise their exclusive jurisdiction only within the 12 miles, and, beyond this, the exploitation of seabed areas—such as the extraction of resources or the laying of pipelines—would become communal and would require an international authority called upon to coordinate the extraction and division of assets. The lifting of the economic sanctions against Iran in January 2016 led Tehran to the center of the regional geopolitical chessboard. The main infrastructure for transporting Iranian gas to the west is the Tabriz-Ankara gas pipeline, with exports of approximately 10 bcm per year, despite having a capacity of 16 bcm.

Since 2009, Iran has developed various upstream gas projects and, with the lifting of the sanctions, has reached phase 21 of the development of the South Pars gas field in the Persian Gulf. The country also has huge gas reserves in the deepest part of the Caspian Sea, but does not have the technology required to extract them. Tehran has repeatedly declared its willingness to transport its natural gas to Europe, originally through the—now dismissed—Nabucco gas pipeline project. With the lifting of the sanctions, Iran is now able to relaunch its export policy, but the fall in crude oil prices is driving the country to look to the more profitable Asian markets. In recent months, Iranian officials have repeatedly stressed the impossibility of constructing a gas pipeline to transport gas extracted from South Pars to Europe via Turkey, due to the long distance (1,800 km) and transport costs. The Tehran government has therefore established the development of infrastructure for gas liquefaction as a priority.

At the same time, Tehran and Moscow are pushing for the creation of a North-South Corridor to connect Russia, Azerbaijan and Iran, offering new prospects for common energy policies towards Asia and Europe. Iranian President Hassan Rohani and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev have met seven times over the past two years, and there are approximately 450 Iranian companies operating in Azerbaijan. The intensification of relations between Baku and Teheran is proceeding on par with the increasingly strong relations between Moscow and Tehran: a framework that could drive Azerbaijan and Iran to join the Eurasian Economic Union, led by Moscow.

TAPI pipeline

Since the 1990’s, there has been talk of a gas pipeline travelling from Turkmenistan to Pakistan, passing through Afghanistan. Back then, under the auspices of U.S. President Bill Clinton, the Central Asia Gas Pipeline consortium was formed, led by the U.S.’s Unocal and Saudi Arabia’s Delta Oil. The idea was to transport natural gas from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean, thereby creating an alternative route for exports to Europe presently controlled by Russia. In this way, it was thought, Moscow would lose strategic control of the Central Asian republics. But there was a problem: despite the withdrawal of Soviet troops, Afghanistan continued to suffer from the civil war. It was therefore decided to unify the country by using the Students of the Quran, the “Taliban,” using Saudi funding and the military support and intelligence of Pakistan. In effect, the Taliban imposed its control over most of Afghanistan, but their plans did not coincide with those of the U.S. administration. The Students of the Quran formed an alliance with al- Qaeda, whose leader, Osama bin Laden, launched an air strike directly against the United States, bringing down the twin towers of the World Trade Center and hitting the Pentagon. That was September 11, 2001.

The project was revived in 2010 when the governments of the four countries, affected by the route of the old project, signed a memorandum of understanding for the construction of the TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) pipeline. To date, however, only preliminary agreements have been signed, and $200 million has been allocated to the feasibility study. The 1,800-km long pipeline is expected to start from the Turkmen gas field of Galkynish, located 200 km west of the Afghan border; it will travel 773 km across Afghanistan, crossing the provinces of Herat, Kandahar and Helmand; it will then travel another 872 km across Pakistan, passing through the provinces of Multan and Quetta, and will finally reach Fazilka, a city located in the north Indian province of Punjab.

The resulting pipeline, the cost of which is estimated at approximately $10 billion, is expected to have a capacity of approximately 90 mcm of natural gas per day, which would be distributed as follows: 38 mcm to India, 38 mcm to Pakistan and 14 mcm to Afghanistan, which has, however, recently reduced its requirement to 4 mcm. The main problem is security. Afghanistan is still suffering from an endless armed conflict, the Helmand province is controlled by Islamic extremists, and even the western provinces of Pakistan, the so-called tribal areas, are beyond the control of the government in Islamabad.

The Arctic, the new frontier

The gradual melting of polar ice has sparked the interest of the superpowers towards the world’s most inhospitable region. From the era of the first specific satellite surveys until the end of the ’70s, Arctic ice has lost half its volume, and this trend does not appear to be stopping. In 2007, the European Space Agency (ESA) declared the so-called “Northwest Passage”—that is, the route connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific passing through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago into the Arctic Ocean, which has historically been blocked by ice—totally passable. Slightly more complex, however, is the situation of the “Northeast Passage,” the route that reaches the Pacific Ocean, starting from the North Sea and continuing in the Arctic Ocean, along the coast of Siberia, crossing the Bering Strait and the Bering Sea, to reach the eastern coasts of Asia. Until recently, this route was considered dangerous due to the presence of ice and icebergs, and was not included in the ordinary trade routes between China and Europe. The melting of the ice, however, has made navigation possible from July to November, even for normal merchant ships, with great advantages for companies that transport goods from China to Europe. According to climatologists, if global warming continues at the current rate, between 2030 and 2050 the Northeast Passage would become safely navigable all months of the year. Quite a long time, but not that long for the nations bordering the Arctic, which may claim rights over the seas surrounding it, to start doing something to defend their interests.

In twenty years, the Arctic routes could become the world’s main shipping routes, avoiding dangerous bottlenecks such as the Strait of Malacca, which is still infested by pirates; politically unstable or disputed areas, such as the China Sea; passages subjected to heavy freight, such as the Suez and Panama Canals, further decreasing navigation times. There is another factor that makes the North Pole one of the most important geopolitical stages on the planet. According to estimates dating back a decade, 30 percent of all conventional gas reserves are in fact enclosed in the Arctic, 13 percent of which are oil, and which also contain large deposits of a variety of minerals, such as uranium, gold and tungsten. Estimates will certainly be revised upwards, as systematic explorations and, therefore, precise analyses, have never been conducted. The country most interested in knowing the situation is Russia, which already derives approximately 15 percent of its GDP from resources located beyond the Arctic Circle. To give an idea of the stakes, suffice it to say that on June 15, 2016, the CEO of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, said that the potential of the largest oil field off the coast of Western Siberia, in the Kara Sea, is equivalent to that of Saudi Arabia.

未经允许,不得转载本站任何文章:

-

- Linda

-

石油圈认证作者

- 毕业于南开大学传播学专业,以国际权威网站发布的新闻作为原始材料,长期聚焦国内外油气行业最新最有价值的行业动态,让您紧跟油气行业商业发展的步伐!

石油圈

石油圈