许多专家认为,被称为“蓝金”的天然气将是不可替代的过渡能源。现在及将来,关于“蓝金”天然气主要运输线路的地缘政治和基础设施问题有哪些?管网建设存在何种挑战?本文将介绍近年来全球范围内十大最重要的天然气管道项目。

来自 | AGE

编译 | 白小明

后石油时代,天然气是大势所趋。俄罗斯“北溪”天然气管道(Nord Stream)扩建项目、意大利和阿尔及利亚的GALSI输气项目、地中海丰富资源储量的开发、南部天然气走廊(SGC)的相关利益及猜想、土耳其天然气管道及向东北的通道面临的挑战……这些项目的发展历程和轨迹你都知道吗,本文将为你一一解读,同时聚焦于全球天然气管网的最新动态。

一、“北溪”天然气管道——输送能力翻倍

由于俄罗斯希望绕开乌克兰、波罗的海国家和波兰,再加上“南溪”天然气管道项目(South Stream)的搁浅,俄罗斯政府开始支持扩建“北溪”天然气管道,并使其输送能力翻倍。

自2011年以来,“北溪”天然气管道就已经通过波罗的海将俄罗斯的LNG输送到德国。扩建项目计划在现有两条管道的基础上,新增两条管道来增加输送能力。“北溪”项目建设中积累的经验有望在扩建项目中加以利用,但由于目前还在进行环境影响评估,且有关各方的意见还未统一,最终线路的提案还未确定。另外,该项目受到沿途各国法律的约束,管道将穿越各国的水域或专属经济区,涉及国家包括俄罗斯、芬兰、瑞典、丹麦和德国。在最近的一份报告中,欧洲议会认为“北溪”天然气管道2号线违背了欧盟的利益。

新的天然气管道预计有约1200公里位于波罗的海海底,并延伸至德国的Greifswald。与“北溪”天然气管道一样,两条管道的输送能力均为275亿方/年。“北溪”天然气管道2号线总共需要大约10万根24吨的钢管,管道单根长12米、内径为1153毫米、表面涂有水泥砂浆并铺设在海床上。管道的铺设和焊接将由专用船完成,由波罗的海沿岸港口提供后勤支持。该管道目前由俄罗斯天然气(Gazprom)的子公司控股、总部位于瑞士Zug的一家公司负责设计、建造和管理;Nord Stream 2 AG公司正在审核国际管道供应商的报价。该公司还得到了Wintershall(德国)、荷兰皇家壳牌(英国和荷兰)、OMV Ag(奥地利)和Engie SA(法国)等公司的支持。根据项目当前的进度计划表,管道铺设工作将于2018年开始,“北溪”天然气管道2号线的两条管道均将于2019年年底前投入运行。

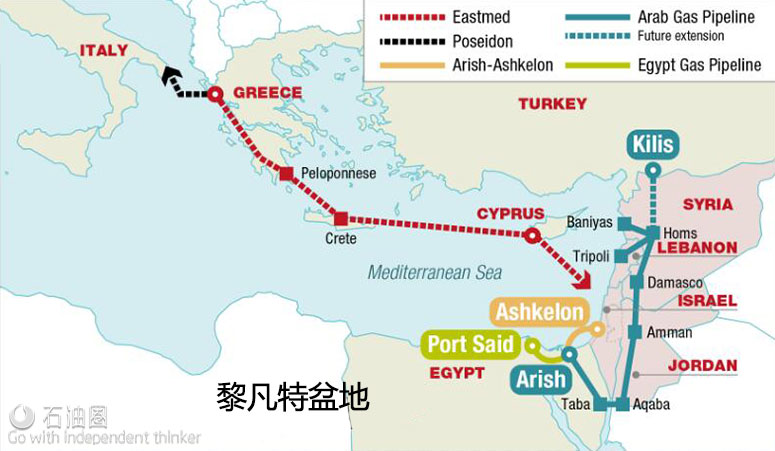

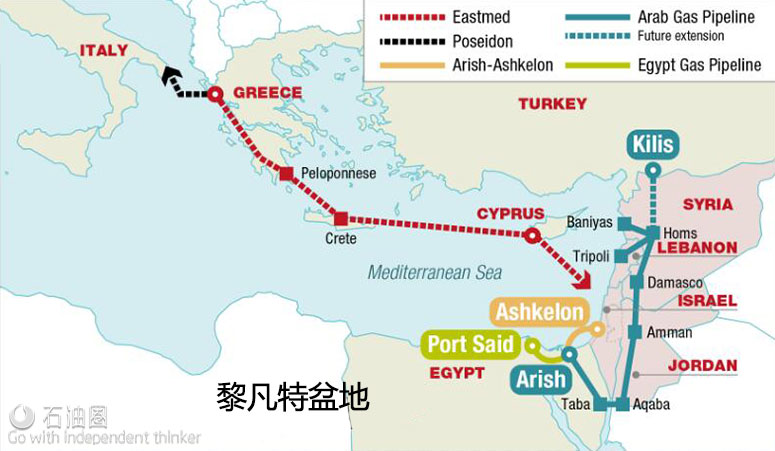

二、黎凡特盆地

黎凡特盆地(东地中海)的油气新发现,将彻底改变欧洲油气供应的地理格局。以色列沿岸的Leviathan大型气田(4500-6000亿方)、埃及海岸的Zohr超大油气藏(8500亿方),以及富含大量天然气的塞浦路斯Aphrodite气田(2000-3000亿方)或将可以满足欧洲的能源需求。然而,资源运输方面仍然存在不确定性。

•第一个也是最现实的选择,是通过现有的埃及Idku和Damietta液化厂出口天然气。2016年8月31日,埃及和塞浦路斯两国签署了建设水下管道的协议,将天然气从塞浦路斯的经济区输送到埃及,然后通过管道输送到埃及的液化厂。此外,在满足国内需求且产能过剩的情况下,有两个已建成的终端可以出口埃及天然气。以色列、塞浦路斯和希腊已经同意建设从塞浦路斯沿岸运输产自Aphrodite气田的天然气的共同基础设施。埃及、塞浦路斯和希腊的领导人也已于2015年12月9日在雅典签署了一项联合声明,旨在让区域各国遵守国际法的合并原则,将油气作为促进和平的催化剂。

•第二个选择,涉及到加强区域间合作,是通过延长阿拉伯天然气管道,使其连接到埃及、约旦、叙利亚和黎巴嫩。这一选择有利的条件是运输天然气所需的大部分基础设施都已建成。但是,其可行性取决于一些地缘政治因素,例如以色列与其阿拉伯邻国之间的关系,西奈半岛地区的不稳定以及叙利亚冲突的发展态势。

•第三种可能性,是在东地中海铺设海底管道,通过希腊大陆将克里特岛(Crete)与意大利相连。此方案得到了欧盟的大力支持,其联合资助了该项目的技术和商业可行性研究。然而,东地中海天然气管道项目预计成本非常高,而且来自塞浦路斯和以色列气田的天然气数量可能有限。

•最后一种解决方案,是通过土耳其的专属经济区,铺设一条天然气管道,将以色列的天然气从Leviathan气田输往欧洲。之前,土耳其和以色列公司就已经签署了建设基础设施的协议,但各种地缘政治因素使项目充满不确定性。虽然原因各不相同,但塞浦路斯、埃及、希腊和以色列都对土耳其表达了强烈的不信任。

三、非洲和欧洲之间:GALSI输气项目

“GALSI”是Gasdotto、Algeria、Sardegna、Italia(即阿尔及利亚-撒丁岛-意大利天然气管道项目)的首字母的缩写,该输气项目旨在建设一条将阿尔及利亚的天然气经撒丁岛出口到意大利大陆的天然气管道。

项目于2003年开始筹划,由于诸多原因于2011年停工,这些原因包括:撒丁岛环境运动的抗议、合作公司在供应成本上存在分歧,以及地缘政治阻碍。项目最初计划于2014年开始运行,经撒丁岛,连接阿尔及利亚东部的Koudiet Draouche和意大利的Piombino。2003年成立了总资本为1000万美元企业财团,包括阿尔及利亚的Sonatrach(41.6%)、Edison(20.8%)、Enel(15.6%),SFIRS–Sardinia地方政府(11.6%)和Hera集团(10.4%)。自2007年以来,Snam Rete Gas公司(意大利)也参与了该项目,并被委托建设和管理撒丁岛段管道。作为创始公司之一的德国化学巨头巴斯夫的子公司Wintershall于2008年2月离开了财团,将其股份出售给了其他股东。

撒丁岛环保人士认为,天然气管道按对角线隔断整个岛屿,要求的最小宽度为40米,这将使数百条水路面临风险。关于财团公司之间的分歧,意大利公司要求天然气成本与价格波动较大的现货市场挂钩,从而利用预期的市场低迷期赚取利润;而另一方面,阿尔及利亚希望天然气按固定和预定的价格供应。尽管该项目被列入到了具有共同利益的项目清单里,但当前仍处于搁浅状态,在SFIRS退出财团后,各方也考虑了在撒丁岛建设两个气化终端的可行性:一个在Porto Torres(Sassari省),一个在Sarroch(Cagliari省)。

四、南部天然气走廊

由于欧盟希望推动天然气基础设施建设项目,从而确保欧洲能源供应的多样化及安全性,因此有了南部天然气走廊(SGC)项目,从阿塞拜疆向欧洲输送天然气。管道总长约4000公里,穿越七国,涉及行业十多家大公司,该项目需要约450亿美元的总投资。包括Shah Deniz气田二期开发,在里海钻井及生产海上天然气,以及扩建阿塞拜疆里海沿岸的Sangachal制造厂。项目涉及三个计划中的基础设施:南高加索阿塞拜疆-格鲁吉亚天然气管道(SCPX)、从阿塞拜疆到土耳其的跨安纳托利亚管道(TANAP)和希腊、阿尔巴尼亚和意大利之间的跨亚得里亚天然气管道(TAP)。

TAP将穿越希腊和阿尔巴尼亚,到意大利的莱切省,长度为870公里,输送能力为100亿方/年,可扩大至200亿方/年。当前联合股东为意大利的Snam、英国BP和阿塞拜疆的SOCAR,分别占20%,另外还有比利时的Fluxys(19%)、西班牙的Enagás(16%)和瑞士的Axpo(5%)。

而TANAP天然气管道是土耳其和阿塞拜疆两国达成协议的结果,计划经土耳其将阿塞拜疆Shah Deniz II的天然气输送到TAP。管道于2015年3月开始铺设,预计于2018年开始向土耳其供应第一批天然气,TAP完成后,阿塞拜疆天然气预计于2020年前几月交付到意大利。目前TANAP的股东是SOCAR(58%)、土耳其的BOTAS(30%)和BP(12%)。

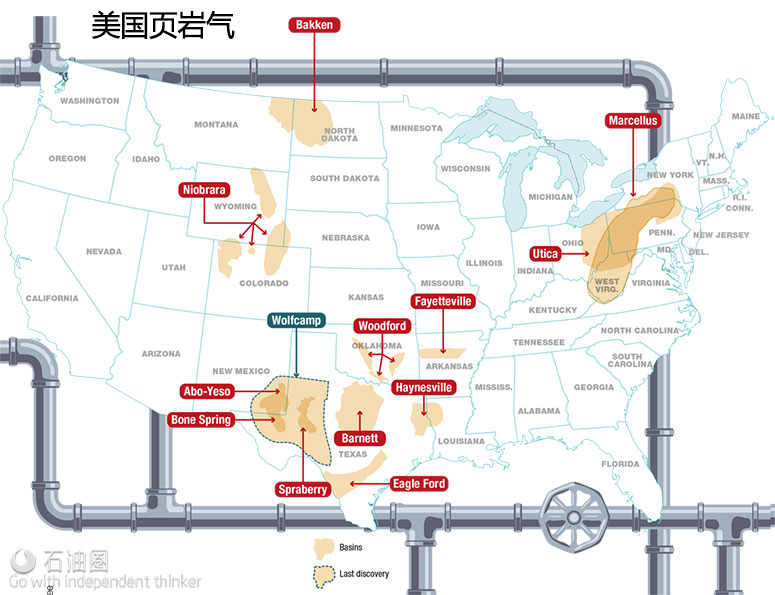

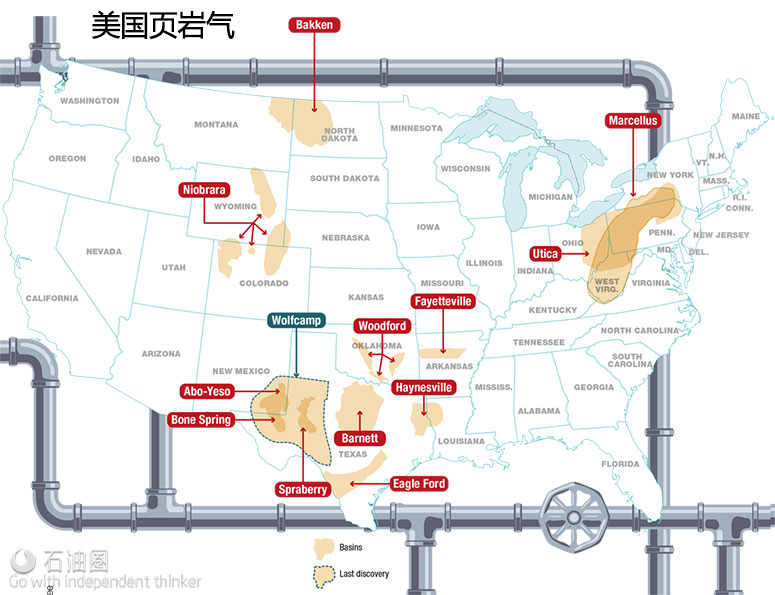

五、美国页岩气

2016年11月15日,美国地质调查局宣布,在西德克萨斯州发现了美国最大的页岩油气储层,即 Wolfcamp页岩,拥有约4530亿方天然气和200亿桶石油,约为美国年需求量的3倍。虽然该地区以前勘探并没有什么发现,但当前的非常规油气采收法、水平井钻井和水力压裂技术使勘探发现成为可能。这一发现增加了美国的油气预估储量,已使其成为了世界上最大的天然气生产国,并且拥有最大的储量。

2015年,根据EIA提供的最新数据,来自油页岩的天然气的产量达106万方/天,即美国总产量的50%。据预测,在未来几十年内,产量将继续稳步增长,在2040年达到22.7亿方/天。主要的天然气产地为Marcellus和Utica,并延伸到宾夕法尼亚州、西弗吉尼亚州和俄亥俄州。另外两个主要的储层为Haynesville和Barnett,分别位于德克萨斯州,以及德克萨斯州和路易斯安那州交界。据预测,仅Marcellus和Utica两个产地,在2040年的产气量将达到11.3亿方/天,相当于总预计产量的一半。然而,美国总共约有30个州拥有页岩气储量。

非常规油气大规模生产始于2000年左右,Mitchell能源公司在德克萨斯州的Barnett页岩采用了水力压裂技术,自20世纪80年代以来,该公司一直在现场试验各种油气采收技术。当天然气变得商业可采后,其他公司也开始对页岩气开采产生兴趣,2005年产量达到近141.6亿方/年。随着开采技术的改进,也开始开发其他页岩储层,如阿肯色州的Fayetteville,德克萨斯州和路易斯安那州交界的Haynesville,俄克拉何马州的Woodford以及Marcellus和Utica大气田。2015年,美国页岩气产量达到近11.3亿方/天,除了市场波动影响外,产量似乎还将增长。

What are the geopolitical and infrastructure-related issues of the main gas routes–present and future–of blue gold transport? Here we consider Russia’s plan to expand Nord Stream; Italy and Algeria’s consideration of GALSI; the exploitation of the rich deposits in the Mediterranean; interests and assumptions that revolve around the Southern Corridor; Turkish Stream and the challenge of a passage to the northeast. The time is right for a focus on global gas networks: their current status, potential developments and the parties driving them.

The doubling of Nord Stream

Russia’s desire to circumvent Ukraine, the Baltic countries and Poland, along with the abandonment of the South Stream project, have prompted the Russian government to support the doubling of Nord Stream, the gas pipeline that since 2011 has transported Russian LNG to Germany via the Baltic Sea. The plan is to increase the transport capacity by adding two new pipelines to the existing two. The knowledge gained from the construction of Nord Stream is expected to facilitate the technical planning, but the proposal of the final route is still pending environmental impact assessments and the opinion of the parties concerned. The project is subject to national legislation in each of the countries whose waters and/or exclusive economic zones are crossed by the pipeline: Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany. In a recent report, the European Parliament established that Nord Stream 2 is contrary to the Union’s interests.

The new gas pipeline is expected to extend for approximately 1,200 km on the seabed of the Baltic Sea to Greifswald in Germany. As with Nord Stream, both of the two lines will have a capacity of 27.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year. Composed of individual pipes measuring 12 meters each and with an internal diameter of 1,153 millimeters, Nord Stream 2 will require approximately 100,000 24-ton steel pipes, coated with cement mortar and laid on the seabed. The laying and welding of the pipelines will be carried out by specialized vessels aided by logistic support from ports on the Baltic coast. The company Nord Stream 2 AG is currently reviewing international proposals for the supply of pipes. The company responsible for designing, constructing and subsequently managing the gas pipeline is headquartered in Zug, Switzerland and is currently 100 percent controlled by a subsidiary of Gazprom (Russia). Nord Stream 2 AG also uses the support of Wintershall (Germany), Royal Dutch Shell (United Kingdom and the Netherlands), OMV Ag (Austria) and Engie SA (France). According to the project’s current schedule, the installation work should begin in 2018 and both Nord Stream 2 pipelines should become operational by the end of 2019.

The Levant Basin

The new hydrocarbon discoveries in the Levant Basin (Eastern Mediterranean) could radically change the geography of supplies to Europe. The large Leviathan natural gas field (450-600 bcm) off the coast of Israel, the supergiant reserves of Zohr (850 bcm), along the coasts of Egypt, and the large quantities of gas found in the Cypriot gas field of Aphrodite (200-300 bcm) could potentially meet the energy needs of Europe. However, there is uncertainty regarding the transport of these resources.

The first and most realistic option would be to export gas via the existing Egyptian liquefaction plants of Idku and Damietta. On August 31, 2016, Cairo and Nicosia signed an agreement for the construction of underwater pipelines that would transport natural gas from the economic zone of Cyprus to Egypt, to then be piped into the Egyptian liquefaction plants. Moreover, the two terminals are already prepared to liquefy and export Egyptian gas, in the event of surplus production with respect to domestic needs. Israel, Cyprus and Greece have already agreed on the construction of common infrastructure for transporting gas from the Aphrodite gas field along the coasts of Cyprus. The leaders of Egypt, Cyprus and Greece also signed a joint statement in Athens on December 9, 2015, with the aim of using hydrocarbons as a catalyst for peace “through the adherence of the countries in the region to the consolidated principles of international law.”

The second option involves strengthening interregional cooperation by extending the Arab Gas Pipeline, the pipeline connecting Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. The positive aspect of this option is that most of the infrastructure needed to transport gas already exists. However, its feasibility depends

on certain highly volatile geopolitical factors, such as the relations between Israel and its Arabic neighbors, instability in the Sinai Peninsula region and the development of the conflict in Syria.

A third possibility is one that plans for the construction of an underwater pipeline in the Eastern Mediterranean, one that connects the island of Crete to Italy, passing via the Greek mainland. This solution is strongly supported by the E.U., which has co-funded a technical and commercial feasibility study of the project. The East Med gas pipeline, however, is expected to have very high costs, and the amount of gas derived from Cypriot and Israeli gas fields could be limited.

The final solution is to pass via Turkey, by constructing a gas pipeline that would transport Israeli natural gas from the Leviathan gas field to Europe, passing via the Turkish Exclusive Economic Zone. In the past, Turkish and Israeli companies signed agreements for the construction of the infrastructure, but various geopolitical considerations make the construction problematic. Cyprus, Egypt, Greece and Israel all harbor a strong distrust of Turkey, albeit for different reasons.

Between Africa and Europe: the GALSI

The GALSI project, which stands for Gasdotto Algeria Sardegna Italia (Algeria, Sardinia, Italy Gas Pipeline), is aimed at the construction of a gas pipeline to export natural gas from Algeria to continental Italy via Sardinia. Founded in 2003, the project was stopped in 2011 for several reasons: the protests of Sardinian environmental movements, the disagreement between partner companies over the cost of supplies, as well as geopolitical obstacles. The initial plan for the gas pipeline, the construction of which was due to start in 2014, called for connecting Koudiet Draouche (in easter Algeria) to Piombino, passing via Sardinia (Porto Botte and Olbia). The corporate consortium, established in 2003 with $10 million in capital, comprised Algeria’s Sonatrach (41.6 percent), Edison (20.8 percent), Enel (15.6 percent), SFIRS – Sardinia Region (11.6 percent) and Hera Group (10.4 percent). Since 2007, Snam Rete Gas has also been involved with the project, under an agreement that had entrusted it with the construction and management of the Sardinian segment. Despite being one of the founders, Germany’s Wintershall, a subsidiary of the chemical giant BASF, left the consortium in February 2008, selling its shares to the other shareholders. Sardinian environmentalists argued that the gas pipeline, by diagonally cutting the entire island and requiring a minimum width of 40 meters, would put hundreds of waterways at risk.

As for the disagreement between the companies in the consortium, the Italian companies pressed for the cost of gas to be linked to the spot market, with a high fluctuation in prices, in order to exploit forecasts of a downturn in the market. Algeria, on the other hand, wanted a supply at a fixed and predetermined price. For now, the project remains suspended, despite being placed on the list of Projects of Common Interest and, following the exit of SFIRS from the consortium, the feasibility of building two regasification terminals in Sardinia: one in Porto Torres (province of Sassari) and one in Sarroch (province of Cagliari) is being considered.

The Southern Gas Corridor

The Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) was founded because of the European Commission’s desire to promote infrastructure projects capable of ensuring the diversification of energy sources and the security of energy supplies, thanks to the transport of gas from Azerbaijan to Europe. With a route almost 4,000 kilometers long, the crossing of seven countries and the involvement of a dozen major companies in the industry, the plan requires overall investments of approximately $45 billion. This includes the second phase of exploitation of the Shah Deniz gas field (Shah Deniz II), the construction of wells and the production of offshore gas in the Caspian Sea, as well as the expansion of the Sangachal manufacturing plant on the Caspian coast of Azerbaijan. There are three planned infrastructures: the South Caucasus Azerbaijan-Georgia gas pipeline (SCPX), the Trans-Anatolian pipeline from Azerbaijan to Turkey (TANAP) and the Trans-Adriatic pipeline, between Greece, Albania and Italy (TAP).

• The TAP will pass through Greece and Albania to land in Italy, in the province of Lecce, with a length of 870 km and a capacity of 10 bcm per year, expandable to up to 20 bcm. The current shareholders of the

consortium are Italy’s Snam, Britain’s BP and Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, each with 20 percent, plus Belgium’s Fluxys (19 percent), Spain’s Enagás (16 percent) and Switzerland’s Axpo (5 percent).

• The TANAP gas pipeline, on the other hand, is the result of an agreement between Ankara and Baku and is expected to transport Azerbaijani gas from Shah Deniz II via Turkey, to then connect to the TAP. The construction of the gas pipeline commenced in March 2015. The first gas supplies to Turkey are planned for 2018 and after the completion of the TAP, Azerbaijani natural gas is expected to be delivered to Italy in the first months of 2020. The current shareholders of the TANAP are SOCAR (58 percent), Turkey’s BOTAS (30 percent) and BP (12 percent).

Shale gas in the U.S.

On November 15, 2016, the U.S. Geological Survey reported the discovery in West Texas of the largest deposit of shale hydrocarbons ever found in the United States. The Wolfcamp Shale, it was announced, held 16 thousand billion cubic feet of gas and 20 billion barrels of oil, or approximately three times the country’s annual need. While the area had already been previously explored without success; unconventional extraction methods, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) now made it possible. The discovery could mean that estimates may rise again, already making the U.S. the largest natural gas producer in the world by far, and one with the largest reserves.

In 2015, according to the latest data provided by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the production of natural gas from oil shale reached 37.4 million cubic feet of natural gas per day, that is, 50 percent of the United States’ total production. According to forecasts, production will continue to grow steadily over the coming decades, reaching 80 billion cubic feet per day in 2040. The main sites, known as Marcellus and Utica, extend into the subsoil of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio. The other two main deposits known, Haynesville and Barnett, are located in Texas and between Texas and Louisiana, respectively. The sites of Marcellus and Utica alone, according to forecasts, will, in 2040, provide 40 billion cubic meters of gas per day, equivalent to half of the total estimated production. In total, however, there are about thirty U.S. states that have shale gas reserves. The large-scale production of unconventional started in around 2000, with the the fracking of the Barnett Shale in Texas by Mitchell Energy which, since the 1980s, had been experimenting with various extraction techniques at the site. When the commercial viability of the gas field became apparent, other companies became interested in its development, with its productivity in 2005 reaching almost 500 billion cubic feet of gas per year. With the refinement of extraction technologies, exploitation began of other deposits, such as Fayetteville in Arkansas, Haynesville in Texas-Louisiana, Woodford in Oklahoma, and the maxi-gas fields of Marcellus and Utica. In 2015, U.S. shale gas production amounted to almost 40 billion cubic meters per day and, apart from the fluctuation owing to the market, appears to be set to grow.

未经允许,不得转载本站任何文章:

-

- Linda

-

石油圈认证作者

- 毕业于南开大学传播学专业,以国际权威网站发布的新闻作为原始材料,长期聚焦国内外油气行业最新最有价值的行业动态,让您紧跟油气行业商业发展的步伐!

石油圈

石油圈