Horizontal multistage fracturing has opened up new oil and gas plays, revived old ones and bolstered production per well as much as tenfold since the technology was developed about 15 years ago.

But as horizontal wellbore sections have lengthened to multiple kilometres and frac stages have increased—with record wells into the triple digits—obtaining real-time information about downhole tool performance during fracturing operations has remained a challenge.

Since the cost would be too high to monitor each frac stage in each well using conventional techniques—such as microseismic arrays, tracers or distributed acoustic sensors (fibre-optic cables run inside the wellbore or outside the casing)—completions companies have been left in the dark as to whether frac balls have launched correctly or downhole sleeves have opened properly for each stage. And missing just a few stages of a multistage fractured well could have a dramatic impact on its initial and ultimate recovery.

That knowledge gap prompted Packers Plus Energy Services to develop a new monitoring technology that can be mounted at the wellhead, detect the real-time operation of downhole tools for each frac stage and be inexpensive enough to install on a routine basis. Its ePLUS Retina Monitoring System, which entered the market about 18 months ago, uses both pressure and acoustic signals to monitor downhole events.

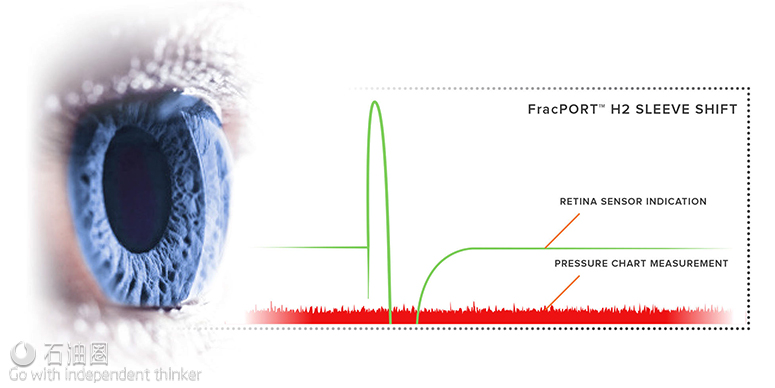

While certain downhole events produce distinct pressure signals, they may occur too quickly to be detected with conventional equipment. Other events, such as ball launches and perforation charge detonation, do not have pressure signatures but can be acoustically detected. The Retina system solves both these challenges, says Barry Hlidek, manager of the Fracture Sciences Group at Packers Plus.

“The beauty of [Retina] is we can monitor certain wellbore events in real time in a relatively economical way, and it’s completely non-invasive: you don’t have to open the wellhead or anything like that. It is magnetically attached to the outside of the wellhead and easy to install—one person can do it in a half hour,” he says.

“We have been using it primarily to verify ball launch and ball seating in multistage sliding sleeve fracture treatments, so we can actually hear or see the ball launch using electroacoustic and electromagnetic sensors. You have not only a visualization graph, but you can also listen to it. We can hear the downhole sleeve shifting,” he says.

The sensitive instrumentation specifically developed for Retina includes high-resolution pressure transducers with a sampling rate of 10,000 data points per second, compared to one reading every second with standard monitoring devices. This is important since events that occur in less than a second can otherwise be missed.

“We actually see sleeves shift in about 0.4 seconds, so they may not be detectable at all by the frac crew because it happens too fast,” Hlidek says.

By observing such events with Retina, a company can continue completing a well without the downtime that might otherwise be necessary to confirm an event took place. “It also helps a lot to verify the ball launches and the sleeve openings because you don’t want to over-flush that treatment,” he says.

In multistage fracture operations, progressively larger balls are launched down the horizontal wellbore into progressively larger seats along its length. When each ball is seated, it shifts an associated sleeve to allow fracturing of that stage, a process repeated up the wellbore. Studies have shown that more successful ball seat landings correlate to higher production.

In one case study of a completion operation in Texas, ball launch and seat indications were not observed during stage five of a 16-stage completion. Rather than shut down operations and take apart the wellhead to determine if the ball had launched, the operator continued to complete the well as if it had launched. The stage six ball subsequently dislodged the stage five ball, which was still in the launcher, and the two balls landed and shifted stages five and six just 45 seconds apart. The two events for each stage were clearly captured by the Retina system, inferring that stage four was stimulated twice and stage five not at all, according to the case study.

The cost and revenue lost in one of 16 stages is significant, the paper concludes. “With estimated drilling and completions expenses of approximately $5 million, each stage costs $312,500. Potential revenue from production is also lost, and reserves in the field remain untapped.”

Retina can confirm ball seating and sleeve shifting in a variety of ball-drop completion systems and is compatible for open-hole and cemented applications. In another case study of a third-party frac operation, the Retina system was able to provide dual verification of several actuation balls having extruded through their seats by capturing an abrupt decrease in pressure along with acoustic detection. Obtaining such accurate real-time information allows the company to take immediate corrective action.

A better understanding of downhole operations can improve critical decision making in a wide range of operations, Hlidek says. “We have also been able to verify explosive perforations, that the perfs have gone off, from surface. We can hear some changes in the noise of the surface equipment that can be an early warning of the failure of that equipment, such as fracturing pumps, and then take appropriate action in real time. Some other things we can do are verifying certain types of packer setting and post-stimulation operations like milling operations and coiled tubing clean out,” he says.

Retina has been used been used in all regions of North America and in the Middle East by operators large and small, says Hlidek. Packers Plus continues to refine the technology based on experience in the field.

随着压裂长度和级数的增加,实时监控井下压裂作业情况迫在眉睫,现有的常规监测技术价格高昂,并不能用于每级压裂的监控,为解决上述难题Packers Plus公司的ePlus视网膜系统应运而生。

随着压裂长度和级数的增加,实时监控井下压裂作业情况迫在眉睫,现有的常规监测技术价格高昂,并不能用于每级压裂的监控,为解决上述难题Packers Plus公司的ePlus视网膜系统应运而生。

石油圈

石油圈