油价的持续走低、美国页岩气的大发现、已探明石油储量的增加、新能源的冲击……这些因素使曾经辉煌的石油行业正经历着剧变,石油巨头们纷纷开始转移业务重心,改变商业策略,以期获得长久发展,而有些人仍不肯接受现实。

来自 | Economist

编译 | 白小明

有人将西德克萨斯州的Midland称之为“德克萨州的海湾地区”,在该地区,基本上每40英亩的土地上就有一台抽油机,从深达3700米二叠纪盆地的页岩地层开采石油。在小城边缘的二叠纪盆地石油博物馆,有一个古董“磕头机”的展览,最古老的磕头机可以追溯到20世纪30年代。在博物馆的后面,一台磕头机正缓缓地上下摆动工作着。

然而,汽车往北开20英里,便可以看到数百台风力涡轮机呼呼作响旋转着,完全掩盖了比涡轮机矮太多的磕头机的风采。远处的棉花地,在早秋的阳光下闪烁着白光,此情此景便是变革中能源行业的一个简单写照。

抽油机及附件的风力涡轮机

您可能会认为,身处困境中的石油人会怨恨像涡轮机这样的新能源产品,因为正是这些产品让世界不再需要化石燃料。但石油生产商Joshua Johnson却看好这些新技术,他管理着该地区的一系列石油租约,很乐意向代理商展示自己所储存的原油,他认为随着世界能源需求的增加,可再生能源将成为石油的重要补充能源,但不赞成过多地考虑全球变暖,他认为无论化石燃料消耗量如何,全球气温总会越来越高。

尽管当前的石油市场处在20世纪90年代以来的最低迷时期,但二叠纪盆地却成为了石油开采的最新热土,它正经历着投资小高潮。自2016年5月以来,该地区的钻机数量增加了60%,而在美国的其他页岩盆地,钻机数增加量微乎其微。尽管钻井工作量仍然低于2014年高峰时的一半,但已钻完井的水力压裂工作量正在重新多起来,在Midland附近,大型的红色卡车再次聚集在油气井周围,在高压下将流体和砂子泵入井内。

今年到目前为止,美国的金融机构已向本国石油公司提供了超过200亿美元资金,主要用于资产收购以及二叠纪盆地页岩气井的压裂工作。该地区最大生产商之一的先锋自然资源公司CEO Scott Sheffield估计,二叠纪地层包含许多2.5亿年前形成的富含石油的储层,可采石油储量可以比得上沙特的Ghawar油田,后者的储量超过了沙特总石油储量的一半。不过,这可能只是他个人的想法,但在另一方面,也说明美国石油业正在逐渐恢复。

二叠纪盆地页岩气大发现是一个综合了运气、地质、技术、法律和勇气等因素发现巨大石油资源的典型例子,这一发现似乎解决了业界老生常谈的石油何时用完的问题。Blake Clayton在其最近出版的新书《市场的疯狂:一个充满石油恐慌、危机和崩盘的世纪》中描绘了全世界担心出现“石油峰值”的四个时期:第一个时期是汽车的出现,当时油价开始飙涨;第二个时期与第二次世界大战同时发生;第三个时期在20世纪70年代,当时OPEC推动了油价上涨;第四个时期从21世纪头十年的中期开始,油价逐渐上涨至140美元/桶,然而这些担心其实是多虑的。

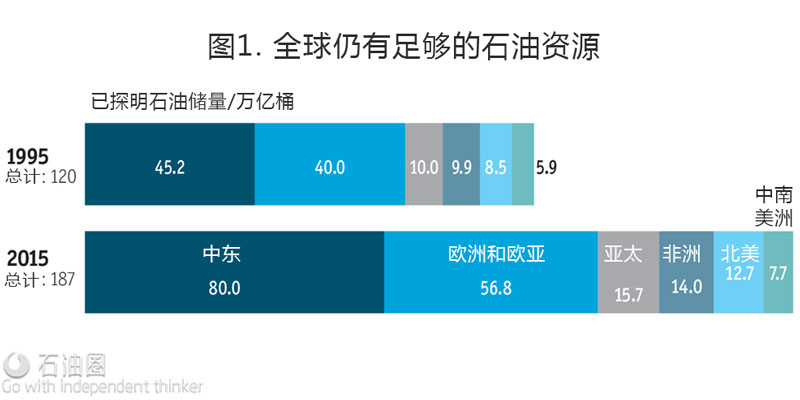

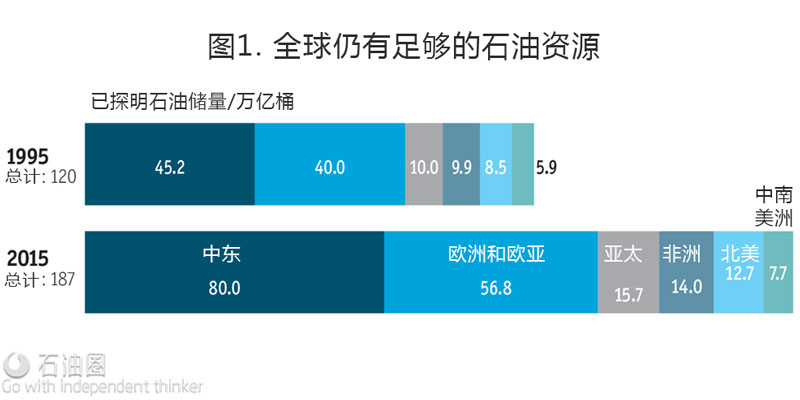

石油峰值论的创始人King Hubbert早在1956年就预测全球石油供应量永远不会超过3300万桶/天,而当前的石油供应量为9700万桶/天。根据BP的数据,在过去20年里,全球已探明石油储量增长了50%,按照当前的速度,石油还可以持续开采约50年(图1)。

好事过头反成坏事

已探明石油储量过多可能并不是好事,反而对行业来说不利,即违背了“物以稀为贵”的理论。

随着大家对气候变化关注的增加,政策制定者、监管机构和投资者已经从担心石油短缺,转向担忧产量过剩。专家们表示,在最极端的情形下,如果将全球变暖温度控制在2ºC以内,成功的可能性是50%,那么今后只需消耗35%的已探明化石燃料储量,主要是煤和石油。如果将目标限定在1.5ºC以内,则只需消耗10%的已探明储量即可满足全球能源需求。正如Clayton在书中写的一样,在石油被淘汰之前,全世界的油井不会干涸。

先锋公司的Sheffield也同意上述石油在淘汰前不会用完的观点,而其许多美国同行却有截然不同的看法。Sheffield认为,由于全球经济增长缓慢,以及大规模引进以可再生能源为动力的电动汽车,全球石油需求可能在未来10-15年内达到峰值。他表示,为了迎接石油需求峰值的到来,先锋公司正在考虑出售其在美国其他地方的资产,专注于二叠纪盆地页岩资源的开发,他认为在当前石油需求量不断减少的情况下,该地区的开发成本还是很有竞争力的。

受近两年油价下跌的影响,一些与先锋公司一样、规模较大的综合性石油公司,特别是欧洲的石油公司,正在改变未来石油发展策略。例如,荷兰皇家壳牌因钻井成本太高,退出了北极项目;道达尔也因类似的原因不愿意进一步投资加拿大油砂项目。

不过他们都清楚,如果石油需求量长期减少,只有开采成本最低的油气公司才能获得长久发展。壳牌CFO Simon Henry表示,该公司预计未来5-15年内全球石油需求将达到峰值,壳牌打算将精力集中在他们认为开采成本最低的区域,如巴西的深水项目,预计该项目在上述预期时间内可以收回投资。另外,壳牌和道达尔都将削减石油勘探投资,同时,道达尔也希望能找到低成本的石油,并期望海湾地区的石油一直保持较低的开采成本,他们还购买了阿布扎比附近的一份为期40年的一小部分石油开采权。

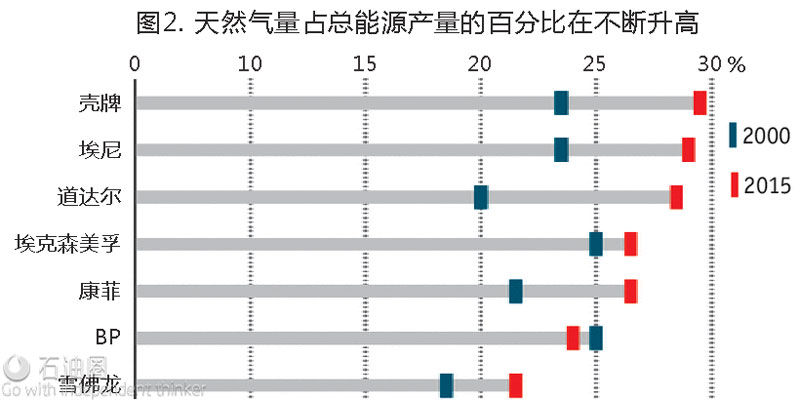

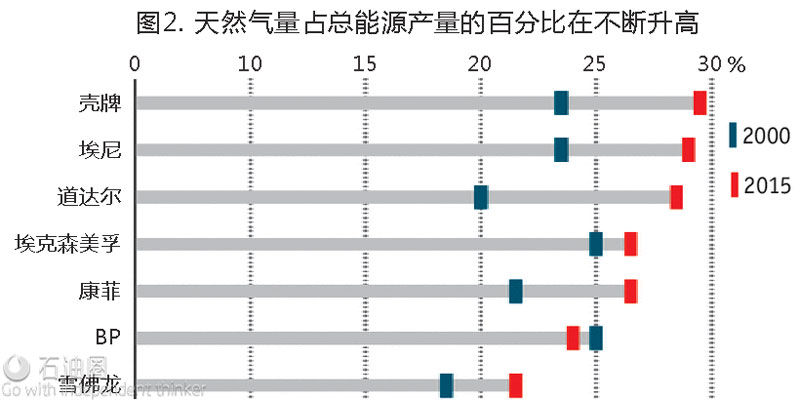

由于大部分石油都产自西方油企难以掌控的OPEC国家,一些石油巨头正在转向天然气业务,作为对石油业务的补充(图2)。今年,壳牌以540亿美元完成了对BG的收购,使天然气产量占到其能源总产量的接近一半。石油公司称,天然气业务比石油更复杂;由于前期需要更多的资本用于开采及运输管道和新销售系统的建设,因此回报率更低。然而,按照化石燃料最悲观的预计情形,天然气的增长前景仍将好于石油。

如何能确保万无一失?

在当前可再生能源即将迅速发展的初始阶段,一些油气公司也在考虑投资可再生能源技术。道达尔已经收购了电池和太阳能发电企业,尽管其CEO Patrick Pouyanné坚持认为,如果油气业务没有利润,他们是不会进行收购的。壳牌公司CEO Henry也称,公司的商业模式可能越来越类似于主权财富基金,如挪威的主权财富基金,即将大量现金流从石油业转向低碳技术。BP开创了“超越石油”的概念,虽然之后由于太阳能发电投资未能赚钱而匆忙收场,但其5年来正首次考虑将更多资金投向风电业务。当未来能源转型的趋势变得愈加清晰时,这些公司将不得不把数百亿美元投向新能源业务的开发。

波士顿咨询集团(BCG)的Philip Whittaker指出,过去石油项目就像取款机,因为一桶石油的售价远远大于其生产成本。但随着石油越来越难开采,收入与成本的差距正在慢慢缩小,但投资者仍喜欢该行业相对较高的投资回报率。一旦石油公司收回了开发油田的成本,则在未来几十年里可获得大量的现金流。

Philip Whittaker表示,油气公司当前投资可再生能源领域,并不确定在未来能获得像石油一样的高投资回报率。油气公司虽然拥有巨额的资金,并擅长进行大规模投资,但在短期内难以看到可再生能源业务达到足够的规模,公司业务总量占比也不会太大。也许在大众眼里,在高低不平的深海安装大量海上风力发电机的项目,与深水石油钻探项目类似,但如果石油公司开始向电力公司转变,那么他们将只能获得与公共基建项目一样低的风险回报率,而且这些新能源项目需要消费者参与。

近期油气行业的一大焦点,是沙特政府希望通过IPO,公开发行沙特阿美石油公司价值1500亿美元的部分股份,以实施类似的多元化战略,这部分收益将存入一个大规模的主权财富基金,投资石油以外的技术。有些人认为,沙特最近以创纪录的产量水平开采石油,是因其预期石油时代将提前结束,而其他人则认为沙特只是想从其他产油国手中夺回市场份额。

与此同时,在美国,大多数石油公司的行动则似乎更加低调。有人认为,市场的力量远比政府的协调措施更利于减少碳排放,他们指出,页岩气替代煤炭后,碳排放量已减少至十年来的低点。许多人都希望近期行业投资的减少能造成石油供应短缺,进而促使油价在2020年之前攀升。BCG的Whittaker称,届时石油行业很可能将迎来“最后的狂欢”,最终世界将走向电气化时代。

The industry is already suffering upheaval, but part of it is still in denial.

SOME CALL IT “Texarabia”. In Midland, West Texas, every bare 40-acre plot of land appears to have a pumping unit on it, drawing oil from the shale beds of the Permian Basin up to 12,000 feet (3,700 metres) below. One is toiling away in the car park of the West Texas Drillers, the local football team. The Permian Basin Petroleum Museum, on the edge of town, has an exhibition of antique “nodding donkeys” dating back to the 1930s. In a lot behind them a working one is gently rising and falling.

Drive 20 miles north, though, and the pumpjacks are overshadowed by hundreds of wind turbines whirring above them (see picture, next page). In fields of cotton, shimmering white in the early-autumn sun, it is a glimpse of the shifting contours of the energy landscape.

You might think hardened oilmen would resent the turbines pointing the way to a future when the world no longer needs fossil fuels. But Joshua Johnson, who manages a string of oil leases in the area and proudly shows your correspondent the lustrous crude he stores in 500-barrel oil batteries, sees things differently, saying: “I think these new technologies are a wonderful thing.” In his view, renewable energy will be a vital complement to oil as the world’s demand for energy increases. But he dismisses global warming: “It’s always been hotter ’n hell here.”

The Permian Basin is oil’s latest frontier, and it is in the throes of a mini-investment boom, despite the deepest downturn in the oil market since the 1990s. The number of rigs has increased by 60% since May, whereas in other shale basins in America it has crept up only slightly. The hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, from wells that are drilled is picking up; around Midland the sight of big red lorries gathered around a wellbore like circus wagons, pumping in fluid and sand at high pressure, has become more familiar again (though the amount of drilling is still less than half its level at the peak in 2014).

So far this year Wall Street has provided funding of more than $20bn to American oil companies, mostly to acquire assets and frack them in the Permian. Some think that the prospects have been overhyped, but not Scott Sheffield, boss of Pioneer Natural Resources, one of the area’s largest producers. He reckons that the Permian, made up of many layers of oil-bearing rock 250m years old, may have as much recoverable oil as Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar field, source of more than half the kingdom’s oil riches. That is probably wishful thinking, but it suggests that morale in America’s oil industry is recovering after the price crash.

The Permian’s story is an example of how a mixture of luck, geology, technology, law and true grit can keep on delivering oil in copious quantities. Such discoveries appear to settle the industry’s perennial question about how soon the stuff will run out. In his recent book, “Market Madness: A Century of Oil Panics, Crises and Crashes,” Blake Clayton catalogues four eras when the world panicked about “peak oil”. The first was the emergence of the motor car, when oil prices started to soar. The second coincided with the second world war. The third was in the 1970s, when OPEC drove up the price of oil. The fourth began in the mid-2000s as oil began its rise to $140 a barrel. Yet the Jeremiahs have always been proved wrong. M. King Hubbert, the doyen of peak-oilers, predicted back in 1956 that global oil supply would never exceed 33m b/d. It is currently 97m b/d. According to BP, a British oil company, proven global oil reserves have risen by 50% in the past 20 years, and at current rates of production would last about 50 years (see chart).

Too much of a good thing

As concerns about climate have risen, policymakers, regulators and investors have switched from worrying about a potential oil shortage to fretting about a possible glut. In the most extreme scenarios, experts say that if there is to be a 50/50 chance of keeping global warming below 2ºC, only 35% of proven fossil-fuel reserves (mostly coal and oil) can be burned. If the target limit is to be 1.5ºC, only 10% of the proven reserves can be used. As Mr Clayton writes: “Oil will be outmoded long before the world’s oil wells run dry.”

Pioneer’s Mr. Sheffield agrees, which makes him a heretic among his American peers. He reckons that global demand for oil may peak within the next 10-15 years because of slow global growth and the large-scale introduction of electric vehicles powered by renewable energy. To prepare for that day, he says, Pioneer is considering selling assets elsewhere in America to focus on the Permian, which he argues is cheap enough to compete in a world of dwindling oil demand.

Like Pioneer, some larger, integrated oil companies, especially European ones, are changing their bets on oil’s future, mostly because of the recent collapse in the oil price. For instance, Royal Dutch Shell, the Anglo-Dutch supermajor, pulled out of the Arctic because drilling there would be too expensive. Its French counterpart, Total, is unwilling to invest more in Canada’s oil sands, for similar reasons. But they are also aware that if demand goes into long-term decline, those with the cheapest oil will survive longest. Simon Henry, Shell’s chief financial officer, says the company expects a peak in oil demand within the next 5-15 years. It intends to concentrate on what it sees as the cheapest deepwater reserves in places like Brazil where investments can be recouped within that time frame. It may also cut oil exploration. Total, too, is hoping to find low-cost oil. It has bought a small stake in a 40-year oil concession near Abu Dhabi, in the expectation that Gulf oil will always be cheap.

Largely because the most prolific reserves are in the hands of OPEC countries, and hence difficult for Western firms to get hold of, some oil majors are turning to gas as a complement to oil (see chart). This year Shell completed a $54bn acquisition of BG, a British producer of natural gas and oil, bringing gas close to half its energy mix. Oilmen say the gas business is more complex than oil; it needs more upfront capital to develop, pipelines for transport and new systems of delivery, so returns can be lower. Yet even the most pessimistic scenarios for the future of fossil fuels suggest better growth prospects for gas than for oil.

Belt and braces

Some companies are also taking out options on renewable technologies, in case they grow very quickly. Total has bought battery and solar-power businesses, though its boss, Patrick Pouyanné, insists that without profits from oil and gas it would not have been able to do so. Shell’s Mr Henry says his company’s business model may increasingly resemble that of sovereign-wealth funds such as Norway’s, which redirect the substantial cash flows from oil into lower-carbon technologies. Britain’s BP, which pioneered the concept of “Beyond Petroleum”, only to rue it later because its solar-power investments failed to make money, is gingerly considering investing more in wind for the first time in five years. When the nature of the energy transition becomes clearer, these companies say they may have to invest tens of billions of dollars to develop new energy businesses.

Philip Whittaker of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) notes that in the past oil projects have been cash machines, because the value of an extra barrel of oil can vastly exceed the cost of production. The difference gets smaller as reserves become harder to find, but investors still like the industry’s relatively high risk-return profile. Once an oil firm has covered the costs of developing a field, it can sometimes generate cash for decades.

He says it is not clear that investing in renewables could replicate oil’s risk-return profile. The oil companies have huge balance-sheets and make commensurately large capital investments, but in the short term it is hard to see renewables reaching sufficient scale to become important parts of their business. Perhaps installing large quantities of offshore wind turbines in deep and rough seas would be similar to deep-sea oil drilling. But the more that the oil companies come to resemble electricity companies, the more their risk profile looks like that of a dull utility. They would also have to get involved with their consumers, which is not something this engineering-minded industry could get excited about.

On a much bigger scale, the Saudi government hopes to pursue a similar diversification strategy via an initial public offering of part of Saudi Aramco. Some of the proceeds, estimated at up to $150bn, will be put into a massive sovereign-wealth fund that will invest in technologies beyond oil. Some reckon that the kingdom has recently been producing oil at record levels because it is expecting an early end to the oil age. Others think it simply wants to recoup market share from other producers.

In America, meanwhile, many oil companies seem to want to keep their heads down. Some argue that market forces are better at reducing emissions than co-ordinated action by governments. The displacement of coal by shale gas, they point out, has cut emissions to ten-year lows. Many hope that the recent investment drought in the industry will lead to shortages that will send the oil price rocketing before the end of this decade. But that, says BCG’s Mr Whittaker, could be the oil market’s “last hurrah”, giving a final push to electrification.

未经允许,不得转载本站任何文章:

-

- 甲基橙

-

石油圈认证作者

- 毕业于中国石油大学(华东),化学工程与技术专业,长期聚焦国内外油气行业最新最有价值的行业动态,具有数十万字行业观察编译经验,如需获取油气行业分析相关资料,请联系甲基橙(QQ:1085652456;微信18202257875)

石油圈

石油圈