“The Stone Age did not end for lack of stone, and the Oil Age will end long before the world runs out of oil.” So said Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, former Saudi Arabian oil minister, in an interview in 2000.

Sixteen years later, Yamani’s words neatly sum up the troubled state of the oil and gas (O&G) industry. Although the demise of oil is still some time away, it’s clear that the sector is going through one of the most transformative periods in its history, which will ultimately redefine the energy business as we know it. Navigating change of this scale will require smart, strategic judgment on the part of O&G company leaders. They must tackle cost and investment concerns in the short term while readying themselves to respond to the future impact of inevitable external environmental pressures.

The sensational drop in oil prices — below US$40 per barrel at the end of 2015, down more than 60 percent from their high in the summer of 2014 — reflects rampant supply and weak global demand amid concerns over slowing economic growth around the world, especially in China.

This imbalance is only going to worsen this year. Saudi Arabia continues to pump at full tilt, less concerned about propping up oil prices and more intent on securing market share, hoping to drive out marginal producers, particularly in the United States. As early as the second quarter of 2016, the flow of Iranian oil is likely to increase, adding to the glut. Even Middle East instability, such as the tension that erupted between Russia and Turkey in Syria toward the end of 2015, has not budged crude prices. Consequently, we expect oil prices to remain low for the near future, although it would not surprise us if volatility returns.

The impact of this situation on O&G producers has been rapid and dramatic. In the third quarter of 2014, when oil prices were still above $100 per barrel, the supermajors posted aggregate net income of $22.9 billion, according to Bloomberg. Twelve months later, upstream profits had been wiped out. In response, companies are slashing outlays. They are expected to cut capital expenditures by 30 percent in 2016. Already, some $200 billion worth of projects have been canceled or postponed. Both international and national oil companies are negotiating aggressively for 10 to 30 percent discounts from oil-field service providers. Head counts are affected as well. More than 200,000 employees have been or will be let go in the O&G industry, according to recent company announcements.

This reaction is not enough — or perhaps it is too much. Massive cost cutting may offer some short-term breathing space, but it is a myopic, panicky response that could leave businesses unequipped for the next turn of the business cycle.

What, then, will forward-thinking O&G executives do? If you are one of those executives, you are probably already beginning to think and act differently than you have in the past. It is time to reassess the purpose and strategic direction of your company, and to find a profitable role to play in the new O&G landscape.

O&G executives must address a vital existential issue: how to successfully do business in an increasingly carbon-constrained world.

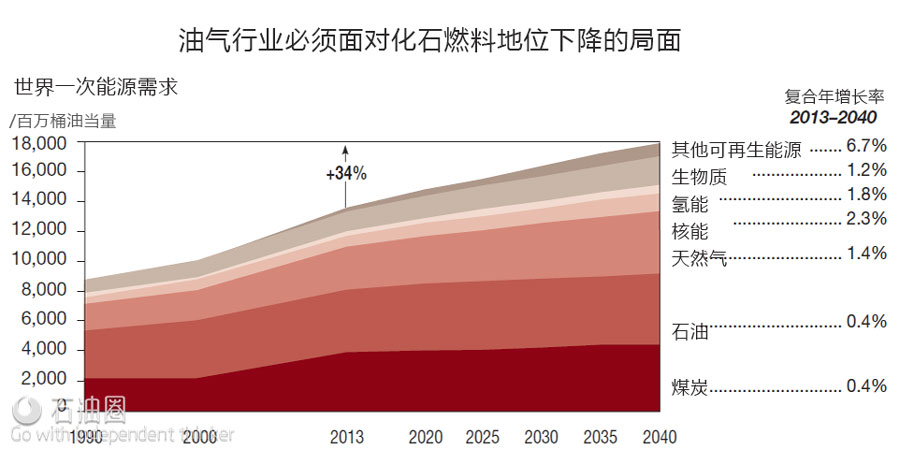

Competition, slumping oil prices, and glutted energy demand are not the only giant-scale factors affecting your business. The O&G landscape is being significantly reshaped by a potent emerging trend: the fear of climate change and a powerful, concerted effort to reduce CO2 emissions and minimize fossil fuels. If you are a business leader in this industry, your most important task this year is to address or at least face up to a vital existential issue: how to successfully do business as an O&G company in an increasingly carbon-constrained world.

zed nations to lessen global warming by curtailing the use of fossil fuels gained momentum in June 2015. The leaders of the G7 industrialized nations issued a communiqué calling for the phasing out of petroleum-based energy by the end of the century. Six months later, nearly 200 nations at the COP21 summit in Paris agreed to a goal of limiting global temperature increases to less than two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels and to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century.

This deal appears to represent a collective commitment by nations large and small to move away from fossil fuel production and consumption. This anticipated outcome of the meeting did not deter the CEOs of 10 of the world’s largest O&G companies (BG Group, BP, Eni, Pemex, Reliance Industries, Repsol, Saudi Aramco, Shell, Statoil, and Total) from declaring their support for what became the COP21 targets a month before the Paris meeting.

Given the reality of diminished fossil fuel use in the future — and the gradual acceptance of that reality in the energy industry — a slew of questions immediately arise. Will upstream oil companies end up with stockpiles of “unburnable” petroleum reserves? If so, should they abandon all exploration activity? Will downstream refiners need to rejigger their configurations to accommodate more biofuels and emission-abatement technologies? Will natural gas–focused companies be better positioned to manage the transition to a low-carbon economy? Should large integrated O&G companies double down on low-carbon technologies in their portfolio?

Facing turbulence and complexity, energy executives need a plan that takes advantage of current conditions and bets on options for a new normal.

These queries demonstrate the turbulence and complexity that energy company executives face — and they are only the beginning. As with any other transformation, managing the uncertainties requires a plan that takes advantage of current conditions and simultaneously prepares the organization to bet on options for a potential “new normal”: a stable business within the maelstrom of change.

For O&G companies, the right plan can be undertaken with three steps.

? First, review the business strategy to refocus your organization on what you do best and where you can best outpace competitors. As the emphasis on fossil fuels wanes, it is critical to avoid becoming overextended in legacy areas. Look for growth areas where you already have massive strength that you can draw on, but where you are agile enough to adapt to changing market conditions.

For example, exploration and production demand two very different business models. Production has significant funding requirements, whereas exploration involves substantially higher risks. All too many exploration firms have delved into production, only to discover that the complexities of these operations, and the capital and skills needed to support them, drain the business of resources and make it hard to do either activity well. Downstream-focused companies have had similarly unsatisfactory experiences when dabbling in upstream activities during the past decade. Those types of missteps and overreaching are potentially disastrous in today’s handicapped O&G market.

? Instead of broadening your business to pursue every opportunity you see, develop a more targeted approach to strategy. For example, Occidental Petroleum spun off its Californian asset into a separately listed company. Now Occidental is focusing on enhanced oil recovery, a sophisticated drilling method that can extend the life of producing fields. Similarly, Apache is emphasizing developing an expertise in managing late-life assets abandoned by the majors; for example, it has acquired the 50-year-old Forties drilling site in the North Sea and intends to extend its productive life by 20 years.

? Second, no matter how difficult things get, avoid arbitrary cost cutting, which can leave your organization ill prepared for an uncertain future. Instead, channel funding into the areas of growth that best promote your differentiating capabilities. In addition, O&G companies must link their investment programs to options that are suitable for a more carbon-constrained operating environment.

? This is not to suggest that you radically change your portfolio and begin deploying wind farms on decommissioned oil platforms. Nor do we forecast that pure exploration and production oil companies will be out of business in 20 years. But in the much shorter term, we think every O&G company will have to figure out how to produce oil competitively while reducing its carbon footprint as much as possible.

? Part of the solution is demonstrating a greater focus on energy efficiency. Statoil has taken steps in that direction by launching an ambitious internal project to review every turbine and compressor it operates on the Norwegian continental shelf. It intends to upgrade or replace equipment as needed to reduce its carbon footprint.

? Even integrated O&G companies should seriously consider incremental diversification, moving gradually into low-carbon technologies to manage the evolution of products as fossil fuels are phased out. For example, figure out whether you have the capabilities to invest in natural gas as a transition fuel. In November 2015, Royal Dutch Shell’s purchase of BG Group made it the world’s largest liquefied natural gas trader.

? This deal and others reflect the fact that natural gas is a preferred fuel for power generation in the U.S. and many other parts of the world, especially as its price has dropped and made it more desirable than coal for cost and environmental reasons. If your company’s strengths are not suited to natural gas, consider acquiring and managing renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and biofuels.

? Third, O&G companies need to exploit new technology to innovate, minimize costs, and help contribute to achieving a lower-emissions environment. For example, as oil prices plunge, demand for digital oil-field applications will grow. Opportunities to link multiple platforms operated remotely from a single onshore center or to deploy remote monitoring for onshore and offshore operations can obviate the need for physical on-site inspections. One supermajor, BP, is already adopting drone technology to inspect pipelines at its remote Prudhoe Bay field in Alaska.

? Look into technology that can retrofit existing equipment for refining and producing renewable energy. Some large O&G companies, including ConocoPhillips, Eni, and Neste, are investing in refining processes to replace diesel with fuel from soybean, palm, and canola oils as well as fats and animal tallow in airplanes and commercial transportation.

In short, as we enter the second year of low prices, every company in the O&G industry will be challenged in a different way. You will have to rise to the occasion, repositioning yourself based on what you do well today as well as on the opportunities you see going forward. Your skill at managing new business is part of this; the industry will hardly disappear, but it will certainly look very different 10 years from now. Some strategies for success are evident; others will be surprising — even to the companies that make them work, for the innovations that make them possible are not yet even on the drawing board.

石油圈

石油圈