Some of the finest mountain scenery in the Southwest US is found in the 1.5 million acres covered by the Carson National Forest. Elevations rise from 6,000 feet to 13,161 feet at Wheeler Peak, the highest point in New Mexico.

Beneath the forest lies the Woodward shale, which was identified in 1967 as an ideal testing ground for an aggressive new method using nuclear explosions to extract natural gas from shale rock. Deemed Project Gasbuggy, the industry (and government) forayed into “atomic fracing.” The technique employed was dubbed “nuclear gas stimulation,” and the theory was similar to modern fracing – employ a great force to open up gas deposits otherwise not commercially viable.

Then as now, critics of the O&G industry claimed that such a method would destroy the local water supply, contaminating it with radiation, and yield other devastating environmental effects on the area. By exploring the story of Project Gasbuggy, we can gain some context around fracing’s real environmental impact. And our conclusion? It seems much of the agenda-driven opposition to modern hydraulic fracturing is, quite frankly, “blown” out of proportion.

From Einstein to the Cold War – The Evolution of Atomic Weapons

The notion of a man-made explosion of enormous power was implicit in Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. The splitting of the atom in 1932 rendered the theory practical. In 1939 alone, more than 100 significant scientific papers on nuclear physics were published and the most important of them, by the Dane Nils Bohr and his American student J.A. Wheeler, explaining the fission process, appeared only two days prior to the outbreak of the Second World War.

The next month, at the behest of Einstein, who was concerned that Hitler would win the race to create what he called an ‘anti-semitic bomb,’ President Franklin Roosevelt established a Uranium Committee, which awarded government grants to leading universities for atomic research. It was the first time federal funds had been used for scientific work.

By 1942, the mechanics of the uranium chain reaction had been discovered and a breakthrough had been made in the production of plutonium. FDR believed that the risk of the Nazis getting a bomb first was very real. He therefore believed that he had no choice but to accord top priority to its manufacture. Accordingly, the Manhattan District within the Army Corps of Engineers (later the Air Force) was founded to coordinate production and resources. The plan was henceforth called “The Manhattan Project.”

On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped the US’s one, untested uranium bomb on Hiroshima, Japan’s eighth-largest city. It caused an explosion equivalent to about 20,000 tons of TNT, and killed 66,000 to 78,000 people. On August 9, the second, plutonium-type bomb was dropped, not on its primary target, which the pilot could not find, but on its alternative one, which was the Christian city of Nagasaki, which on a note of tragic irony was the nearest thing to a center of resistance to Japanese militarism.

Very soon after the conclusion of the Second World War, an “Iron Curtain” descended over Europe in particular, and the Eastern and Western hemispheres generally, with the US and the Soviet Union establishing the restive bipolarity that marked the next 50-plus year Cold War. On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb. Thereafter, the principal existential threat faced by the antagonists in the Cold War was that posed by nuclear weapons.

The first Soviet nuclear test, successfully conducted in 1949, was code named “First Lightning”

In 1950, the US held 299 nuclear weapons in its stockpile. That same year, the Soviet Union held 5. By 1965, the US held 31,139 weapons in its arsenal, and the Soviet Union held 11,643. The arms race had begun, with countries in the US and Soviet spheres of influence accumulating nuclear weapons.

Operation Plowshare: How To Constructively Use Nuclear Weapons

In the late 1950s, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was entrusted with the responsibility of developing techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful purposes. The program was called “Operation Plowshare.” The AEC chairman announced at the time that the project was intended to “highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests.” Toward this end, from 1961 to 1973 researchers executed 27 experiments under the Plowshare program. In total, 35 nuclear detonations were conducted during this period.

The majority of these experiments were attempts to create craters and canals. Other objectives included an inexpensive widening of the Panama Canal, cutting paths for highways through mountainous areas, and connecting inland river systems. These experiments, mostly conducted in Nevada, also occurred in the oil fields of Colorado and New Mexico. Project Gasbuggy was an outgrowth of Plowshare. It was the first of three nuclear fracing experiments that focused on stimulating natural gas production. The technique employed was dubbed “nuclear gas stimulation.” It was hoped that a large nuclear explosion would be capable of opening up gas deposits which are not otherwise commercially viable.

Project Gasbuggy: Nuclear Fracing Pays Off

El Paso Natural Gas Company conceived of Project Gasbuggy in 1958 and proposed it to the AEC, which adopted it as one of the signature projects for the Plowshare Program.

After nine years of development, and an investment of $1.8 million by El Paso Natural Gas in engineering the project, 160 acres were secured in northern New Mexico. The federal government paid an additional $2.9 million, supplying the nuclear device.

On December 10, 1967, the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory and El Paso Natural Gas Company, funded by the Atomic Energy Commission, detonated Gasbuggy. The 29 kiloton explosion detonated in the Woodward shale at a depth of 4,227 feet. By comparison, the nuclear frac’s payload was nearly double that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The detonation created a molten glass-lined cavern roughly 160 feet in diameter and 333 feet tall. Within seconds it collapsed. Measurements taken later showed that the explosion created fractures that extended more than 200 feet in all directions. Especially significant was the fact that natural gas production increased.

The December 22, 1967, edition of Time magazine featured an article entitled, “Nuclear Energy: Good Start for Gasbuggy.” It vividly described the moments before the detonation:

“On a butte above New Mexico’s Leandro Canyon last week, chilled observers fell silent as a voice on the public-address system reached the end of the countdown. For a tense moment, nothing happened. Then the earth jolted underfoot and a dull, distant boom was heard, followed by a second, more gentle, rolling shock. Someone shouted: “We did it! We did it!” Hand shakes were exchanged all around. The U.S. had successfully set off the first nuclear explosion sponsored jointly by the Government and industry.” During the first half of 1969, a series of three production tests were carried out. Records indicate that the Gasbuggy well produced 295 Mcf of gas. However, the gas was found to be too radioactive to be commercially viable. During several of the aforementioned production tests, the radioactive material was removed via flaring.

James Holcomb, the site foreman for El Paso Natural Gas, considered Project Gasbuggy a success. He said, “The well produced more gas in the year after the shot than it had in all of the seven years prior.” Further, the detonation did not kill the water supply. In light of the high symbolism/low-substance arguments of many contemporary fractivists, this is an important observation. It is difficult to see how a deep modern fracing operation could do damage to shallow water formations, especially in light of the fact that a 29 kiloton nuclear bomb detonated at 4,227 feet failed to do so.

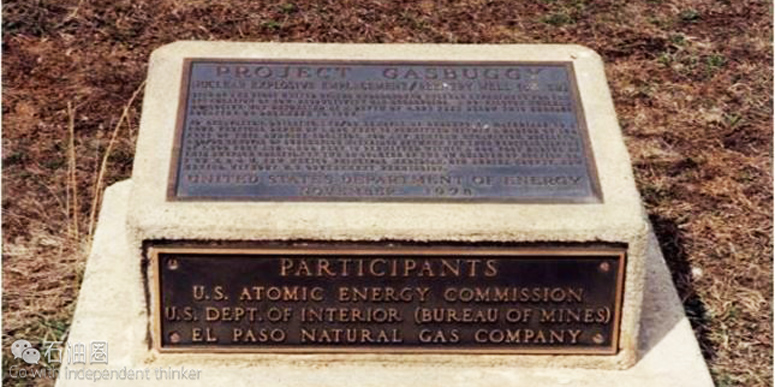

In November 1978, the Department of Energy placed a marker at the site of Project Gasbuggy. It reads as follows: “Site of the first United States underground nuclear experiment for the stimulation of low-productivity gas reservoirs. A 29 kiloton nuclear explosive was detonated at a depth of 4227 feet below this surface location on December 10, 1967. “No excavation, drilling, and/or removal of materials to a true vertical depth of 1500 feet is permitted within a radius of 100 feet of this surface location. Nor any similar excavation, drilling, and/or removal of subsurface materials between the true vertical depth of 1500 feet to 4500 feet is permitted within a 600 foot radius of t 29 n. R 4 w. New Mexico principal meridian, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico without U.S. Government permission.”

Two More ‘Plowshare’ Detonations

Following Gasbuggy, two additional nuclear explosions were carried out in the interest of natural gas extraction as part of Operation Plowshare. Both of these were conducted in Colorado. Nuclear devices were detonated as Project Rulison in 1969 and Project Rio Blanco in 1973. Project Rulison detonated a 40 kiloton device and succeeded in liberating large amounts of natural gas. However, the resulting radioactivity left the gas contaminated. Project Rio Blanco detonated 33 kiloton devices in a single emplacement well at three different subsurface depths.

Gasbuggy Then And Now – A Reclamation Object Lesson

Today, the test area for Project Gasbuggy is part of the beautiful Carson National Forest. Were it not for the monument pictured above, one would have no way of knowing that the area was once the site of a nuclear detonation.

This is so because of the reclamation efforts undertaken at the site in the years since the explosion. Although the process of nuclear gas stimulation has long been abandoned, the process of reclamation has not. Environmental reclamation efforts are one of the most under-reported activities O&G companies undertake. Many companies, including TransCanada and Chesapeake Energy, consistently implement environmental reclamation. Here is a visual example from a modern hydraulic frac site in the Marcellus Shale:

Around the time that Project Gasbuggy was executed, the US was in the throes of a cultural upheaval that would ultimately yield a proliferation of new causes and movements. One of these was environmentalism, which identified both nuclear weapons proliferation and the oil industry as principal antagonists. Whereas in the time of Project Gasbuggy nuclear proliferation and the various dangers it posed were the primary areas of concern for environmentalists, today the wrath of much of the movement is directed toward the key technology motoring the US shale revolution – hydraulic fracturing. Unfortunately, with tiring frequency, anti-fracing activists fail to moor their opposition in reason, common sense, and history. Instead, ideology and uninformed passion seem to fan the flames of ignorance.

The danger attributed to hydraulic fracturing today is nowhere near the potential fall-out of “nuclear fracturing” over 40 years ago. And today, the only evidence that Project Gasbuggy occurred is a small plaque in a pristine environment and historical reports like this one. And while Gasbuggy did contaminate gas production immediately following the nuclear frac, it did not kill the water supply, did not irrevocably harm the environment, and did not poison the local environs with dangerous amounts of radiation. When one recalls Project Gasbuggy, it seems that the agenda-driven opposition to today’s hydraulic fracturing is largely “blown” out of proportion.

石油圈

石油圈