FOR a view of Houston’s economy, get in a car. At the intersection of the Loop and Freeway 225, two motorways in the south-east of the city, you drive over a high, tangled overpass. To the east, where the port of Houston sits on Buffalo Bayou, the skyline is an endless mass of refineries, warehouses and factories: Houston is an oil town. To the west, glistening skyscrapers and cranes puncture greenery. In between, the landscape is a sprawl of signs advertising motels and car dealerships.

Houston is not pretty, but it thrives. In the decade to 2010, the population of its metro area grew more than that of any other American city. Between 2009 and 2013 its real GDP increased by 22%, more than twice as fast as the American economy as a whole. Its growth infuriates new urbanists who insist that dense, walkable places such as Manhattan or San Francisco are the future. The question is, can Houston continue to thrive in an oil bust?

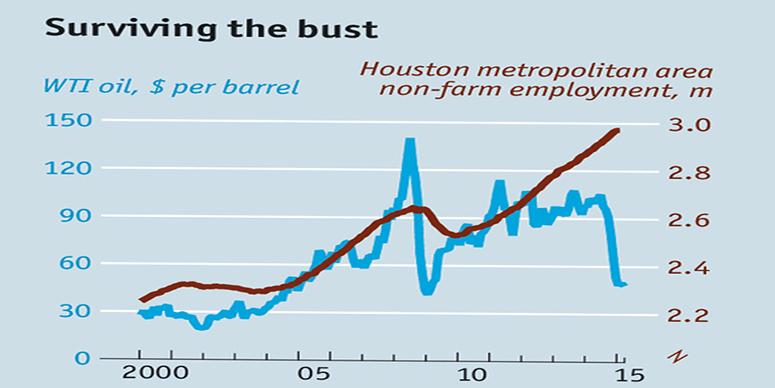

Over two-thirds of the growth in crude oil production in the United States between 2009 and 2014 took place in Texas. As well as refineries and drillers, oil brings office jobs: ConocoPhillips and Halliburton both have their headquarters in Houston, as does BP’s America division. Exxon Mobil is building a huge new campus near The Woodlands, a wealthy suburb north of the city. In the past, oil-price gains and job gains have kept in close step (see chart).

The slump is hitting some businesses already. In Houston, when prices fell, “it was almost like the lights just went out,” says Peter Wyatt, the boss of Micron Eagle, which makes hydraulics for drillers. Last year the drillers’ main concern was simply to get their rigs running as quickly as possible, for which they paid hefty prices. Now, instead of demanding speed, they want discounts. Across America the number of drilling rigs pumping oil has fallen by 38% since December, according to Baker Hughes, an oil-services firm.

With reduced demand, many small manufacturers and suppliers are sure to go bust, says Patrick Jankowski, an economist with the Greater Houston Partnership, a local business lobby. But the real question is whether a more general slump follows. Multinational oil-related firms based in Houston—including Halliburton and ConocoPhillips—have announced job losses in the past few months. If high-paying corporate posts go, the effect on the rest of the Houston economy could be dramatic.

Yet there are signs that, this time, Houston’s spectacular growth will be slowed rather than stopped by the oil slump. Much investment, such as in Mobil Exxon’s new campus, is committed, and will not stop now. Mr Jankowski estimates that Houston could still add as many as 50,000 new jobs this year. That is far less than the annual average of 100,000 or so in recent years, but still enough to hold down unemployment.

The city’s economy has diversified since the 1980s. At the Texas Medical Centre, a collection of hospitals, medical colleges and research institutions about a 15-minute drive from downtown Houston, new office blocks glisten in the spring sun. Over 100,000 people work there. Day trippers flock to the museums and students to the universities nearby. More foreign goods now flow through Houston’s port than any other in America; some 51m people a year now fly through its two airports, one of which, Hobby, is being expanded by Southwest Airlines. And some people and industries will benefit from falling oil prices: commuters, as well as plastics and chemicals firms.

Paradoxically, perhaps the city’s biggest strength is its sprawl. Unlike most other big cities in America, Houston has no zoning code, so it is quick to respond to demand for housing and office space. Last year authorities in the Houston metropolitan area, with a population of 6.2m, issued permits to build 64,000 homes. The entire state of California, with a population of 39m, issued just 83,000. Houston’s reliance on the car and air-conditioning is environmentally destructive and unattractive to well-off singletons. But for families on moderate incomes, it is a place to live well cheaply.

Some wonder if a bubble is inflating. “We have overbuilt the apartment market already and we are well on the way to overbuilding the office market,” says Jim Noteware, a property developer. In recent years the ratio of house prices to incomes in the city, long lower than in the rest of America, has crept close to it. A property slump could hit Houston’s core city—which relies heavily on property taxes—hard. It is already running a hefty deficit and carrying a heavy pension burden.

If disaster is avoided, it will be because Houston has reached a critical mass where employers keep moving in because others are already there. Joel Kotkin of Chapman University in California argues that thanks to cars, even over its vast size, Houston creates the same possibilities for people to meet and share ideas that generate wealth in denser cities such as New York. Sprawl may not be pretty—but it seems to work.

石油圈

石油圈