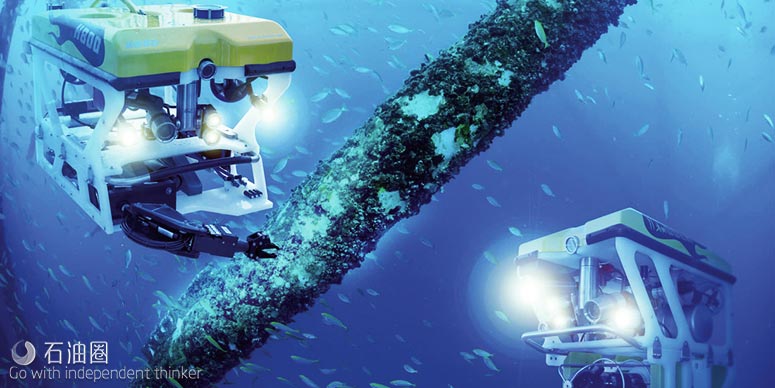

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), or tethered swimming underwater robots, have been described by at least one long-time member of this small part of the offshore industry as “underwater tractors”.

While that may sound dismissive, and somewhat of an understatement considering the sophistication of these machines, this comparison does reflect both the range of tasks that ROVs are asked to do and the flexibility they provide in executing those tasks.

If one considers that a tractor can pull a plough, a harrow, a seed drill and a hay or straw baler, amongst other tasks, it might be that this comparison is no condescension at all. The ROV has, in fact, become much more sophisticated and powerful since the early days of the offshore sector, when it could do little more than observe what was going on underwater. Even then it might not see very much, depending on the turbidity of the water.

One subsea veteran even used to joke that ROVs had to be deployed in pairs, so that the second one could find and rescue the first one when something went wrong. Those days are gone.

Industry veteran Mike Winstanley, now sales and marketing director at MSubsea, notes that when he was first involved with ROVs, in the 1980s, their power rating was just 25 horsepower, while now the big work-class ROVs are up to 250hp.

It is this new added power, plus the capability provided by advanced software, that give ROVs the ability to take on tasks that they have not been asked to do before.

This is one of the big issues for ROV manufacturers and deployers, according to Tyler Schilling of Schilling Robotics, now part of TechnipFMC.

Schilling, who began his career with ROVs in 1985 as one of the founders of his eponymous company, believes that these underwater workhorses are underutilised.

“These machines can do far more than has ever been asked of them,” both in terms of capacity and capability, he says.

And this, despite the fact that their increased workability has meant that they are still doing all of the underwater tasks asked in the past, such as turning valves, lifting modules onto subsea structures and the like, plus a lot more. Eschewing the tractor analogy, Schilling refers to the ROV as “a Swiss Army knife”.

Earlier advances in ROV technology involved hydraulics, Schilling says, because most of the ROV developers were mechanical engineers.

Although a mechanical engineer by training, he believes that the current technology leaps are the result not of hardware improvements, but in software.

He cites the use of simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) technology, developed for use with smart phones.

SLAM allows a device, whether a phone or an ROV, to map the position of the device in the background as it is being used for another task.

“This is the power of processing,” Schilling says, with ROVs benefitting from such emerging technologies that do not require human intervention.

Subsea 7 has a division, I-Tech Services, totally dedicated to robotic activities, indicating the significance of robotics in the context of its total business.

The views of its technologists are not dissimilar to those of Schilling — advanced station-keeping and the increased use of sensors has boosted the capability of ROVs.

One point that its people see as significant is that all this new technology has reduced pilot fatigue, which is beneficial in terms of safety and operations. I-Tech’s staff also see an eventual progression from hydraulically powered ROVs to hydro-electric, and then to all-electric vehicles, which will reduce the cost of operations, increase efficiency and reduce environmental impact.

Diversification

The increase in tasks for ROVs has inevitably led to new types of vehicles and accessories. Higher powered ROVs are not always the answer for certain operations — these beasts are bigger, heavier, and create access issues.

Alan Gebbie, project manager at MSubsea, notes the increased use of mini and micro-ROVs, essentially the equivalent of a drone, which can provide a different type of operational benefit.

Much recent research and development has been devoted to multi-purpose vehicles that combine characteristics of both ROVs and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs).

Modus Seabed Intervention has been working with Saab Dynamics for three years in developing Saab Sabertooth, which can operate either as a conventional tethered ROV or as an AUV (Upstream Technology 1/2017).

When used in resident mode the hybrid vehicle is equipped with a seabed docking station from which it can be launched to carry out specific tasks independent of the host vessel. The Sabertooth can return automatically to the station on completion of its mission, upload data and video to the surface, download new instructions and recharge batteries. The vehicle is designed to accommodate a suite of survey sensors that can be tailored to specific projects.

In battery operation mode, Sabertooth has around 16 hours of operability and can move at up to 4.5 knots, but can also hover like a conventional ROV. Modus’ commercial director Nigel Ward says: “Like many innovations that are being introduced into the market, the main aim is to reduce costs whilst maintaining or improving quality levels.”

When operated in AUV mode, the vehicle can perform a survey, using latest sensor technology, independent of the host vessel.

This allows the host vessel to deploy the unit and then sail off to perform other tasks, such as diving or walk-to-work support on another part of a worksite.

“This flexible capability has applications throughout the subsea industry,” Ward says.

New markets

Much is said these days about offshore renewables filling the gap that the oil and gas sector used to occupy in terms of business activity.

Of course, at one time, it was the oil and gas sector that filled in the gaps in activity for diving and other contractors who worked for the salvage business.

It seems appropriate then that things should come full circle with at least one contractor providing 21 century kit that might have been useful for salvage in the past, although now it is aimed at the other new market, decommissioning.

Utility ROV Services, another relatively new company in the sector, invested £6 million ($7.8 million) last year in a new piece of technology which it calls UTROV. The aim is eventually to build a fleet of five of these units at a total cost of £9 million.

This ruggedised and powered tool carrier has its own thrusters for orientation and positioning and is capable of lifting loads up to 55 tonnes. It is expected to be used across Utility’s three markets, according to business development manager Richard Smith.

In some ways, the UTROV is the latest generation of what was originally called an ROT, or remotely operated tool. These came into fashion in the mid to late 1990s, when manifolds were all the rage and were often used as part of a pull-in package for flowlines and umbilicals.

Other variations were deployed for lifting and retrieving modules within large subsea production systems or even specific pieces of equipment, like meters or control pods.

One of the first applications for the UTROV, according to Smith, will be in conjunction with a mattress recovery tool, which will eliminate the need for divers to be involved in this risky seabed operation.

Smith says that the development of this type of kit is increasingly difficult for smallto- medium enterprises such as Utility. Many are risk averse.

But with the decommissioning market set to boom, Utility hopes to make the most of the upcoming opportunities.

石油圈

石油圈