尽管在过去的40年内,原油价格涨势惊人,但是转折点最终还是到来了。在未来的几十年内,过去的供应稀缺、不稳定、高价格的局面将被供应富足、稳定并且较低的价格水平所取代。

在最近出版的《原油价格 The Price of Oil》一书中写到,页岩气革命将使2035年世界的油气总产量提高2000万桶/天。同时还认为“常规油气藏革命”,及常规油气藏中水平钻井技术和水力压裂技术的应用,将在同一阶段增加近2000万桶/天的产量。这多出来的4000万桶/天的产量几乎是1994年到2014年这二十年间全球石油产量增数的两倍。

这些新兴的产量革命在全球范围内不断发展和壮大,也就注定将对原油价格有着很强的抑制作用。我们认为,原油价格将被压制在2015年的53美元/桶(布伦特)这个水平以下,而且就算出现早前反弹,还是会被拉回这个水平。

现在对于2035年的油价,较为乐观的价格为40美元/桶。但是,如果没有严格的气候政策的限制,那么对低廉原油的使用可能会不断增长,石油在整个全球能源系统中的寿命也要会增加。

碳泡沫的谬论(Carbon Bubble)

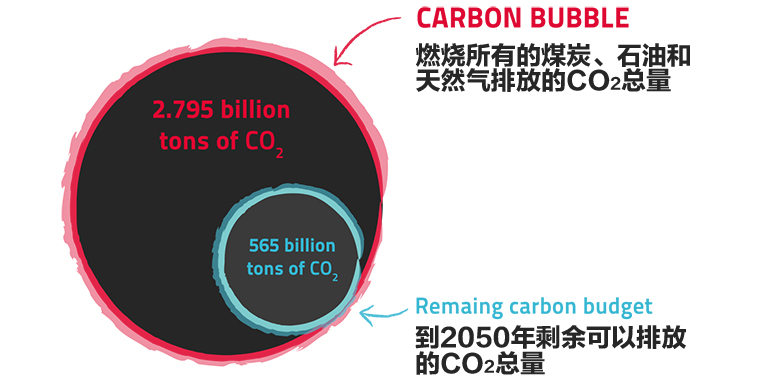

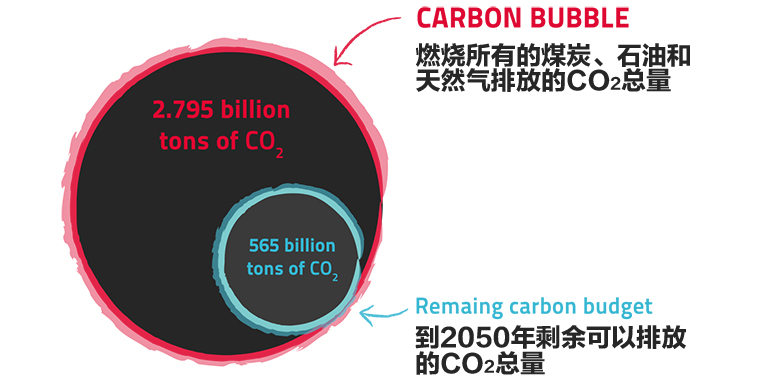

碳泡沫认为在对依靠化石燃料的公司估值时应该考虑其可能产生的二氧化碳量。从上图可以看到,我们可以排放的量已经比较少了。所谓的“碳泡沫”是对石油、煤炭和天然气的高估造成的。根据由斯特恩和“碳跟踪系统(Carbon Tracker)”发布的报告,如果人类想要控制气候变化,至少2/3的储量必须保存在地下。这意味着这些储量将毫无价值,这是市场的巨大损失。)

在现在主导的气候政策中,提出了确保21世纪大气中CO2浓度不超过工业化前水平的两倍,即将全球气候温度增长控制在2摄氏度以内。那么在这样的政策下,与2011年的水平相比,到了2035年全球需要减排30%,到了2050年至少需要减排50%。毫无疑问,如此重大的气候政策一旦实施,意味着近期的石油生产革命走向终结。同时评论家普遍认为这一政策将导致大量资产滞留在化石燃料行业内。

气候政策会导致有相当大的探明储量留在地下进而对化石工业造成严重的打击吗(因为根据气候政策,我们只能开采总探明储量的1/3)?至少我们不这样认为。以原油为例,以目前生产水平我们可以保证在未来50年内的原油储备,而且与生产开发总生产成本相比,原油储存成本很小,因此值得生产商们保持一个合理的平和的心态面对未来生产潜力。

如果气候政策导致了涉及巨额投资的生产设备被迫停用,那么其实这种资产闲置反而会造成更严峻的问题。粗略地假设在未来的几十年内,原油总产量也将与二氧化碳排量相应地下降30%,那么原油产量将从2014年的8900万桶/天降至2035年的6200万桶/天。这将会巨大的改变,但即使如此,我们仍然相信严重的资产闲置问题不太可能会发生。

要知道全球的油井产量平均每年以7%的速度下降,想要稳定产量需要提高对可采储量储备进行的投资,或直接开发新油田。即使最大幅度减少当前的生产能力以满足2035年的气候水平,闲置的设备资产可能不超过5年就会被重新启用。除非有事先的预兆,否则气候政策不可能突然地实施,所以设备闲置的可能性几乎是没有的。

气候政策的成本

为了合理的预测气候政策执行成本,采用最有效的金融分析工具并假设气候政策执行后经济调整灵活度在理想状态下,最终得出每年的成本约为全球GDP总额的1 – 2%(7700亿~15400亿美元)。很明显这会引发政治问题,因为这些成本最终要强加于纳税人或能源用户身上。

由于欠发达国家是目前最大的排放国(图1),并且几乎未来所有的能源需求增长都将来自这些国家,政治问题将变得更加尖锐。

对于这些国家来说,理所当然会对全球减排协定表示不满,因为每个排放单位所承担的减排任务是一模一样的。考虑到发达国家在工业发展史上曾大量的使用石油、煤矿和天然气,那么迫使欠发达国家放弃以相似的方式获得繁荣从而完成减排的任务,则可以说是个在政治和道德都相当敏感的话题了。那么为了让较为贫穷的国家也参与到全球减排计划中,则需要将发达国家的资金转移到其他发展中国家。

在这种背景下,如果世界想要实现上文提到的碳排放目标,那么需要给出一个所需要转移的现金流的数量。估算到2020年,净年转移量为5000亿美元,其中有2000亿美元来自美国。到2050年,每年所需的转移金额将超过30000亿美元,与此同时美国需要承担10000亿美元。在2009年哥本哈根气候会议上,发达国家承诺到2020年给予其他国家每年1000亿美元的补偿,这一承诺在最近的巴黎气候峰会上又被重提。但如果我们将这些补贴加起来看,迄今为止实际的总承诺金额仅约为100亿美元。而且由于这些发达国家中,有些一直面对着国内的政治阻挠,因此就这些少得可怜的经费到最后都可能不了了之。鉴于这些经费的数量,我们不难看到要想搭建目标和实际行动之间的桥梁是多么困难的一件事。

气候政策的前景与影响

事实上,几乎所有能源预测机构都认为化石燃料的需求还将在未来几十年不断扩大,石油继续作为满足世界能源需求的重要组成部分。此外,石油行业的投资行为展现了对未来气候政策的疑惑。我们倾向于分享这些观点,认为资产闲置现象可能会在主要出现在昂贵的可再生能源补贴上,如果这些态度占据上风,将成为政策演变的推手。

另一个需要考虑的问题是,世界上大部分的原油产量都握在发展中国家的国有企业手中。相比于减排,这些企业更优先考虑的是社会和经济的发展。而且,在许多产油的发展中国家,原油消费者享有高额的公共补贴。在政治层面上这些补贴很难取消。同时,他们还鼓励国内消费,即鼓励保持现有的原油产量。

预测未来并不容易,但通过历史和当前的行为表现都可以看出,未来气候政策行动仅仅是浅层的。深度执行气候政策的成本如此之高,加上自签署了京都议定书后混乱及不作为现象犹在眼前,我们有理由怀疑新的气候政策是否能逆转过去的不作为问题。对于刚刚达成巴黎协议,有些国家态度不明朗,有些则延期执行,这些都证实了我们的看法。因此我们得出这样的结论:气候政策不太可能阻碍我们之前预测的石油革命的进步。

作者/Roberto F. Aguilera 译者/周诗雨 朱丹 编辑/Wang Lin

Although oil experienced an extraordinary price increase over the past 4 decades, a turning point has been reached where scarcity, uncertain supply, and high prices will be replaced by abundance, undisturbed availability, and suppressed price levels in the decades to come.

In our new book, The Price of Oil, we conclude that the shale revolution will yield an increased output of oil in the world totaling nearly 20 million B/D by 2035. We also assert that a “conventional oil revolution”—the application of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing to conventional oil formations in the world—will yield a further addition of almost 20 million B/D in the same period. This extra 40 million B/D is nearly twice as much as the global increase in oil production in the 20-year period from 1994 to 2014.

As these new production revolutions develop and expand internationally, they are bound to have a strong price-depressing impact, either by preventing price rises from the levels observed in 2015 (the Brent spot price averaged USD 53/bbl), or by pushing prices back to these levels if an early upward reaction takes place. Our optimistic scenario sees a price of USD 40/bbl by 2035.

Without serious climate policy restrictions, the use of cheaper oil will likely grow and extend its life expectancy throughout the global energy system.

The Carbon Bubble Fallacy

A deep climate policy is one that ensures that CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere do not exceed a doubling from pre-industrial levels throughout the 21st century, believed to be a warming of about 2 degrees Celsius. Such a policy would require global emission cuts of 30% by 2035, and no less than 50% by 2050, compared with 2011 levels. There is little doubt that implementation of climate policy this ambitious implies the end of the recent revolution in oil production. There have also been widespread claims that such a policy would result in massive stranded assets in the fossil fuel industries.

Would sizable proved reserves remaining in the ground due to a deep climate policy constitute a serious problem to the fossil industries? We do not think so, or else, the reserves would never have been created on such a prevalent scale. In the case of oil, the reason proved reserves have been created to last more than 50 years into the future, at present production levels, is that investment in reserve creation is relatively small in relation to total production costs, and therefore worth the companies’ while to assure reasonable peace of mind about future production potential.

The stranded asset problem could raise more serious problems if climate policy resulted in unused production installations whose development has involved heavy investment. Applying the rough and simplified assumption that oil output would be reduced in line with the overall emission cuts referred to earlier of 30% in the coming decades, oil production would be reduced from 89 million B/D in 2014 to around 62 million B/D in 2035. This would be a remarkable change, but even here we believe that serious stranded asset problems are unlikely to occur. Producing oil wells worldwide experience, on average, decline rates of 7% per annum, so stable production requires investments either in reserve growth or in the development of completely new fields. No more than 5 years of ceased investments would then be required to reduce current production capacity to the maximum 2035 level imposed by climate action. In the absence of dramatic and sudden measures imposed without warning, there is little likelihood that installations capable of continued production would be left idle in consequence of interventions to arrest climate change. These considerations raise questions about the realism of stranded asset fears.

Climate Policy Costs

The cost of a rational, deep climate policy, using the most efficient instruments and assuming that economic adjustment to the policy effects will be ideally flexible, has been assessed to amount to perhaps 1–2% of annual global GDP: USD 770–1,540 billion in 2014. Political issues will obviously arise, as these costs will ultimately have to be borne by unwilling taxpayers or energy users.

These issues will become much more profound since less developed countries are now the largest emitters (Fig. 1), and virtually all of the energy demand growth in the future will come from these countries. Yet it is reasonable for them to express an unwillingness to go along with a global emissions deal in which everybody is charged equally for each emission unit. Given the industrialized world’s history of intensive oil, coal, and gas use, it is clearly a politically and morally sensitive issue to deny less developed countries the use of fossil fuels to achieve reduced emissions at the expense of similar prosperity.

Against this background, it may be appropriate to present results showing the order of magnitude of the required dollar flows if the world is to attain the emissions goal referred to earlier, with the non-OECD world’s participation paid for in full by financial transfers. By 2020, the net annual transfers have been assessed at USD 500 billion, of which USD 200 billion would be from the US. By 2050, the required annual transfers would exceed USD 3 trillion, with the US contribution rising to USD 1 trillion. At the Copenhagen climate meeting of 2009, wealthy countries pledged USD 100 billion a year until 2020 in compensation to the rest of the world, a promise renewed at the recent climate summit in Paris. To put these sums into perspective, actual commitments to date amount to about USD 10 billion in total, but even these meager offers are not definitive as they face political resistance in several of the countries making them. Given the relative size of these numbers, it is easy to understand the difficulty in bridging the gulf between the climate rhetoric and the political preparedness to incur the costs.

Climate Policy Prospects and Implications

Practically all energy forecasting organizations predict an expanding fossil fuel future for decades to come, with oil continuing to play a key part in satisfying the world’s energy needs. Moreover, the oil industry’s investment behavior exhibits unbelief in deep climate policy in the foreseeable future. We are inclined to share these views, and contend that the stranded asset phenomenon may come to apply in the main to expensive, subsidized renewables if these attitudes prevail and become instrumental in policy evolution.

Another point to consider in this context is that a vast majority of the world’s oil reserves are in the hands of state-owned enterprises in developing countries. These organizations have goals such as social and economic development, which are likely to be higher priorities than cutting emissions. Moreover, oil consumers in most oil-producing developing countries receive significant public subsidies. These subsidies are politically hard to discontinue. They also encourage domestic usage, and, by implication, the level of production.

Despite the difficulties in predicting what might transpire, history and current behavior point to no more than superficial climate action in the future. The cost of a severe policy is so high, and the confusion and inaction since the signature of the shallow Kyoto protocol so pervasive, that we deem a reversal of past climate policy inactivity to be highly questionable. The noncommittal nature and the extended deferral of action characterizing the just-¬completed Paris agreement support our view. Hence, we conclude that climate policy is unlikely to hamper the progress of our projected oil revolutions.

未经允许,不得转载本站任何文章:

石油圈

石油圈