Search for Oil Yields a New Business Model

Kosmos Energy is a survivor in the shrinking field of deep-sea exploration for oil

Neanda Salvaterra

About 30 miles from the tropical West African island nation of S?o Tomé and Príncipe, a research vessel called the Oceanic Endeavour is mapping a deep swath of the Atlantic Ocean floor on an increasingly rare mission: to make the next big oil discovery.

With oil prices stuck in the third year of a historic funk, many energy companies have retreated from finding new sources of crude. After prices came crashing down in mid-2014, exploration projects that were planned when crude was still fetching $100 per barrel no longer made sense when the price was closer to $50. In the retrenching that followed, many smaller exploration firms sank under the weight of debt amassed when the market was thriving.

One firm that has survived is Kosmos Energy Ltd. KOS 3.29% , a midsize firm based in Dallas that was founded in 2003 and is now financing the survey under way aboard the Oceanic Endeavour. Kosmos has managed to discover and develop several large new fossil-fuel resources on a shoestring budget in tough frontier environments such as off Africa’s west coast—one of the last regions where major hydrocarbon finds can be retrieved. Its latest coup: On May 8 it announced a discovery of an estimated 15 trillion cubic feet of natural gas off the coast of Senegal, where it is part of a joint venture for production with BP PLC.

“We’ve kept clarity through the years on what we are good at,” says Chief Executive Andrew Inglis.

Indeed, while some other companies were taking on debt, Kosmos has kept costs down in part by drilling in areas that some of its rivals thought of as hydrocarbon dead zones—the waters off Ghana, Mauritania and Senegal, and now S?o Tomé. Such an approach helps it avoid competition that leads other companies to pay high signing bonuses to governments looking to lease assets to the highest bidder. Since its launch, the firm also has always targeted a break-even price of $50 a barrel or lower, even as oil prices soared.

Company Watch, a London-based research firm, estimates that some 85 U.K.-based oil-and-gas companies have gone bust since the downturn began, while in the U.S. around 41 publicly listed oil- and gas-related firms filed for bankruptcy, although a little more than half later emerged with new financing.

The future of oil exploration is “a leaner and much more efficient industry,” says Andrew Latham, vice president of exploration research at Scottish energy consultants Wood Mackenzie. “Also a smaller industry.”

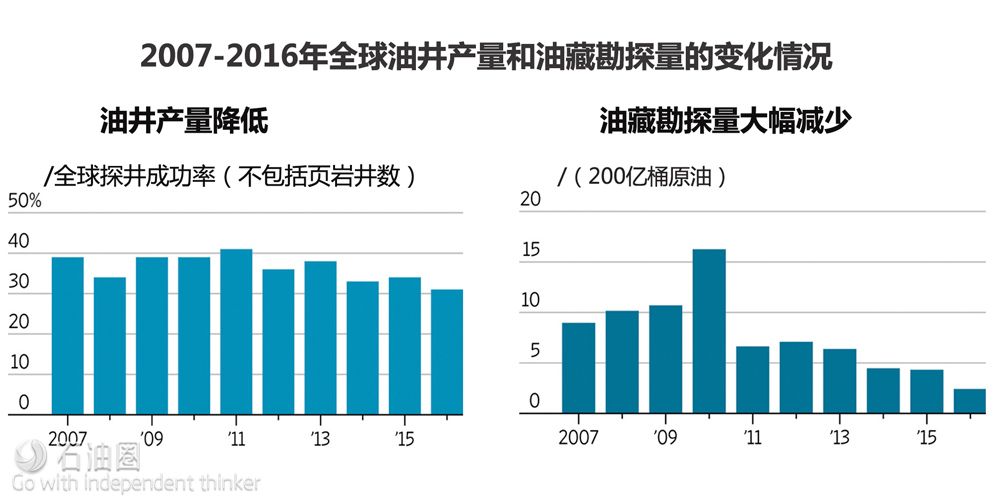

Oil discoveries in 2016 declined to their lowest levels on record as major oil companies such as BP, Royal Dutch Shell PLC and others shrank their exploration programs, according to the International Energy Agency, an adviser to governments across the world. “The appetite from the majors for exploration isn’t as strong as it was a few years ago,” says Fatih Birol, the executive director of the IEA.

Research by Wood Mackenzie confirms that assessment. The firm estimates that big oil companies, including BP, Chevron Corp. , Shell, Exxon Mobil Corp. , Eni SpA and France’s Total SA, have slashed exploration spending by more than half, to $11.7 billion last year from $25.2 billion in 2014.

And the “biggest hit” came in offshore exploration projects, which generally are the biggest, most technologically challenging and most expensive, Mr. Birol says. Last year only 13% of all exploration was offshore, down from an average of about 40% for the past 15 years, according to the IEA.

For new sources of supply now, most companies are building out already-established positions in U.S. shale, finding ways to pump more from currently producing fields or buying stakes in other companies’ assets.

The current state of exploration has some observers in the industry worried. The world could face an oil shortage as soon as 2020 if companies don’t start exploring again, according to a bombshell IEA report released in April.

For those that haven’t stopped, meanwhile, past success is no guarantee of future results. But having fewer competitors does have its advantages. “We are seeing opportunities that were not there for us a few years ago,” says Tracey Henderson, a Kosmos vice president and geophysicist who helps decide where the company goes prospecting for oil and gas.

Indeed, its current undertaking, crisscrossing a section of the Atlantic slightly larger than Connecticut off the coast of Africa’s smallest country, is one of the biggest offshore oil-exploration efforts of its kind in the region. The company makes a habit of conducting large-scale surveys like this one, in an area where other companies have tried but failed to find major crude reservoirs since the 1950s. The company expects the current survey to be complete by August.

“People go into exploring frontier areas and focus on a little postage-stamp spot, and it might not work and then they are done,” says Dorie McGuinness, a vice president of exploration and geology at the firm. “If you are going to explore frontier basins, you have got to have a big scale.”

The company has three major discoveries to its credit. In addition to its recent gas discovery off Senegal, it found the gigantic Jubilee field off the coast of Ghana in 2007, which now produces about 100,000 barrels of oil a day. Proceeds from that funded a major natural-gas discovery in 2015 in waters off Mauritania and Senegal, and other projects.

In addition to going where other firms tend not to, Kosmos takes a long time to pick its targets. Careful deliberations help it to drill fewer test wells, which in turn reduces overall costs. Prospecting in offshore Mauritania and Senegal, it initially drilled only three wells in the Tortue gas field, and achieved a 100% success rate, the company’s engineers say. The industry’s average success rate for drilling test wells in 2016 was 31%, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Kosmos also has one of the shortest turnaround times for extracting oil for commercial sale. It delivered oil for commercial sale about 3? years after its initial find off the coast of Ghana, beating the industry average of six years. A helpful element in that strategy: When it finds oil, like most midsize explorers it also finds big partners to develop the projects and to extract the hydrocarbons. In addition to BP in Mauritania and Senegal, these have included Anadarko Petroleum Corp. and Tullow Oil in Ghana. In S?o Tomé it is working with Galp , the Portuguese oil and gas operator.

Some of the major oil companies have kept their toe in deep-sea exploration. Exxon discovered an estimated 1.4 billion oil-equivalent barrels off the coast of Guyana last year. Eni discovered a vast gas field off Mozambique in 2011, and, more recently, the massive Zohr gas field off Egypt’s coast in 2015.

In addition, a few of Kosmos’s midsize peers, such as Cairn Energy PLC and Tullow Oil, also have had success. Tullow has been drilling onshore in northern Kenya since 2012 and estimates it has found 750 million barrels of crude in the region so far, though the exploration work is continuing.

To help with the availability of capital, meanwhile, as more of the bigger players in oil and gas have departed for safer territories, private-equity funds are seeing more opportunities to invest in exploration.

“We think there is an opportunity in exploration today,” says Peder Bratt, a managing director at the private-equity fund Warburg Pincus, which invests in oil-and-gas exploration and production companies and has a stake in Kosmos. “But future success is going to have to look different than past success,” Mr. Bratt says. “Business models are going to have to adjust.”

Industry experts recognize that deep-water exploration is still going to happen, alongside efforts to exploit known reserves, says Ms. Henderson, the Kosmos executive. But “the best projects” in both places, she says, will feature “the most cost-competitive barrels you can get out of the ground.”

石油圈

石油圈